About our state economy

Many families and communities in North Carolina never healed from the Great Recession before COVID-19 created a new wave of financial harm. Generations of wage stagnation, structural barriers for people of color, and an economy rigged to concentrate wealth in the hands of a few left North Carolina exposed to a crisis like COVID-19. The pandemic exacerbated North Carolina’s pre-existing economic ailments, and it threatens to leave our state more divided, unequal, and vulnerable.

For additional research and data on North Carolina’s economic landscape, consider visiting:

- Labor market coverage: Monthly state and local employment and unemployment data

- Prosperity Watch: Monthly research bite on economic issues facing North Carolina

- Poverty report: Annual report on poverty data for North Carolina

- County Snapshots: Annual economic and social data for North Carolina’s 100 counties

1 Year into COVID-19

Quick recovery for high-wage employees, deep recession for low-wage workers

Quick recovery for high-wage employees, deep recession for low-wage workers

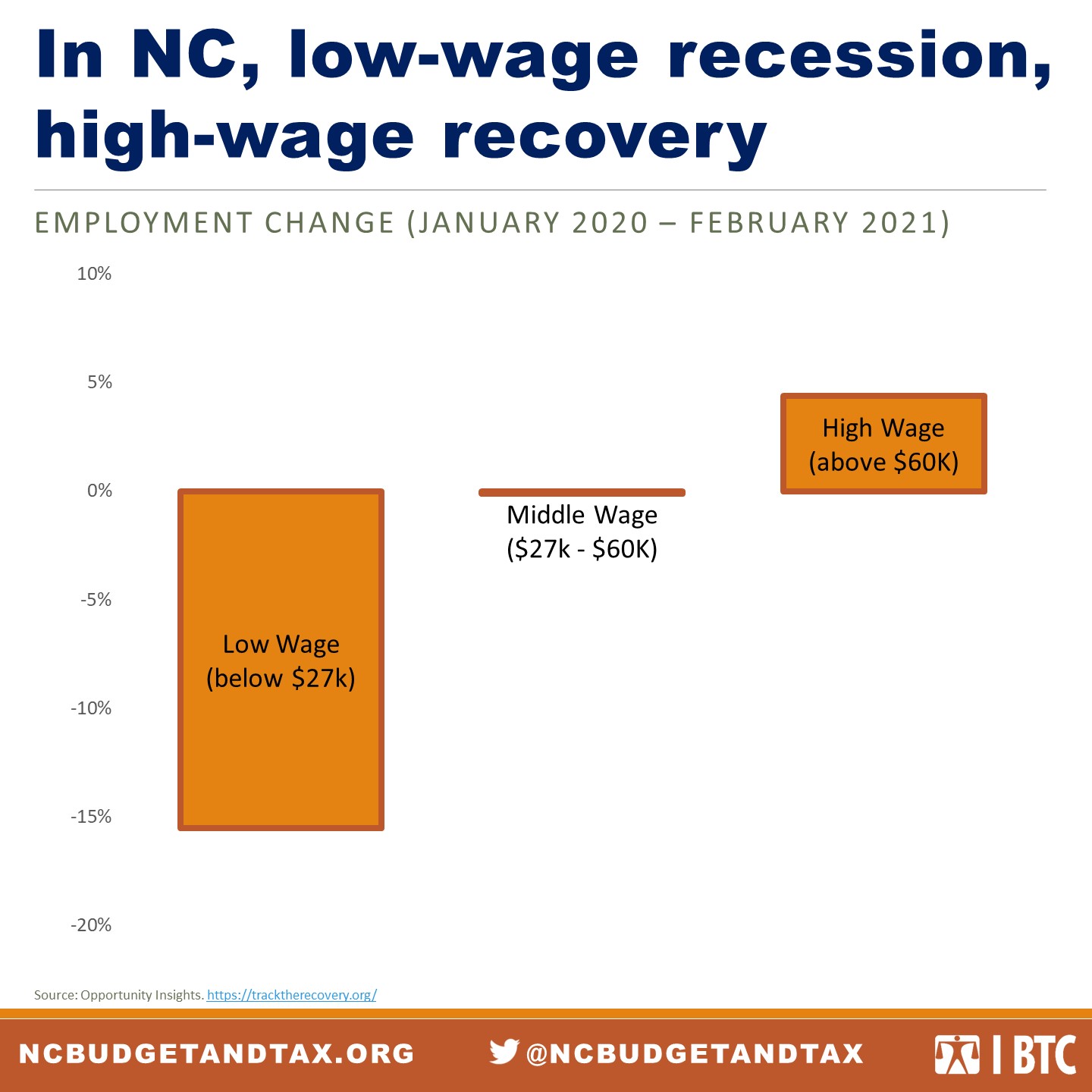

We’re seeing what economists call a k-shaped recovery, where middle- and upper-income jobs bounce back quickly while a deep recession continues for low-wage workers. Even more than in recent recessions, the economic harm is most concentrated on people with the least financial cushion to fall back on, while many well-paid people never experienced any loss of income.

- North Carolina still has not recovered the more than 1 in 7 jobs that pay below $27,000 that were lost during COVID-19

- Jobs paying above $60,000 had recovered to pre-pandemic levels by the end of May 2020, so the recession was effectively over for high-wage workers after only a few months.

- Jobs paying between $27,000 and $60,000 took longer to recover than high-wage jobs, but had returned to pre-pandemic levels by early 2021

Fewer North Carolinians working

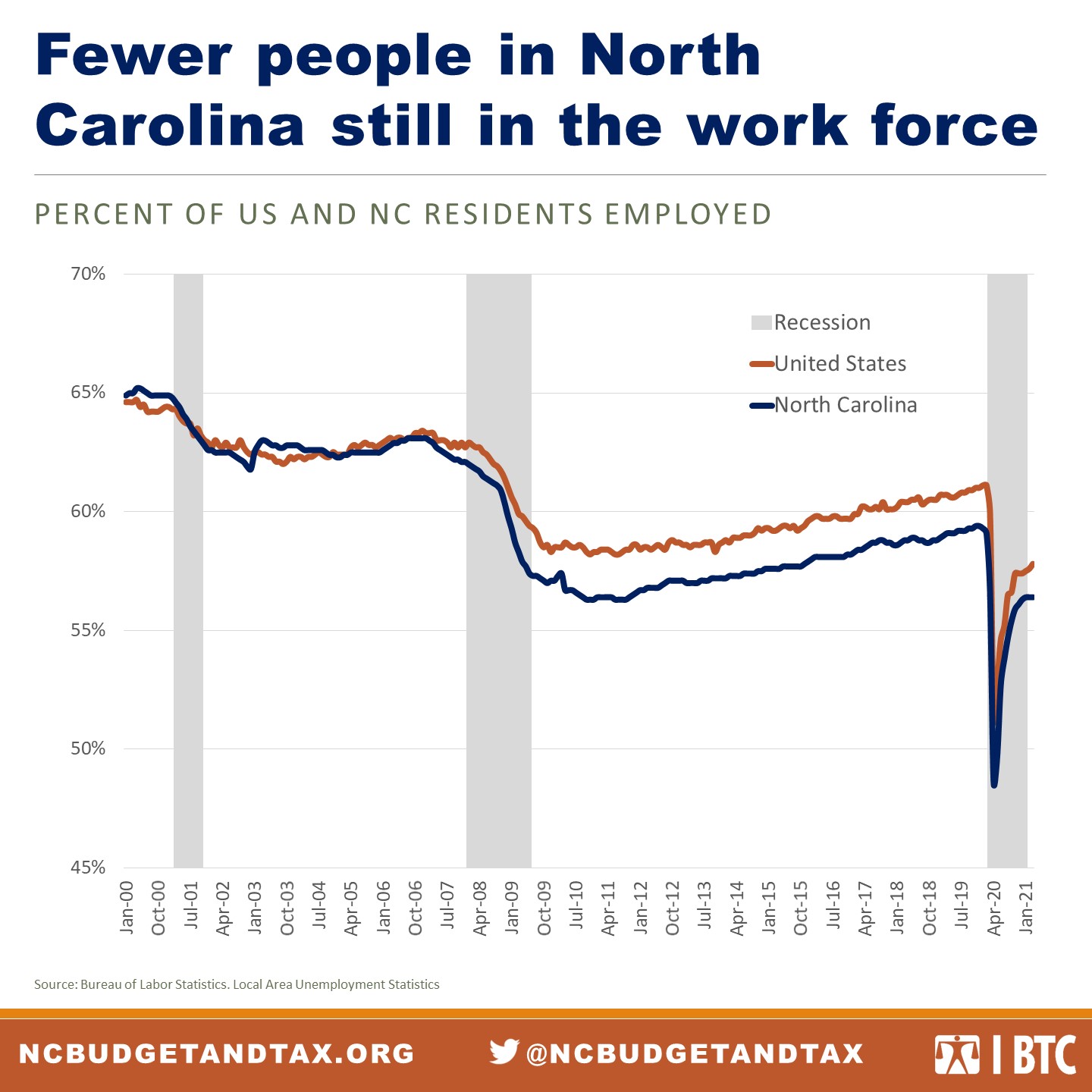

COVID-19 deepened a long-term trend of declining employment in North Carolina. While some of the jobs lost in the first few months have returned, a smaller share of North Carolinians were working a year into the pandemic.

- Only 56.4 percent of North Carolinians were working in March of 2021, compared to over 59 percent before COVID-19.

- The past two economic cycles have decreased the share of North Carolinians working, pushing the state below the national average. Nearly 65 percent of North Carolinians were working in 2000, which had fallen to 62 percent before the Great Recession, it and has stayed below 60 percent since the financial crash in 2008.

Racial unemployment disparity

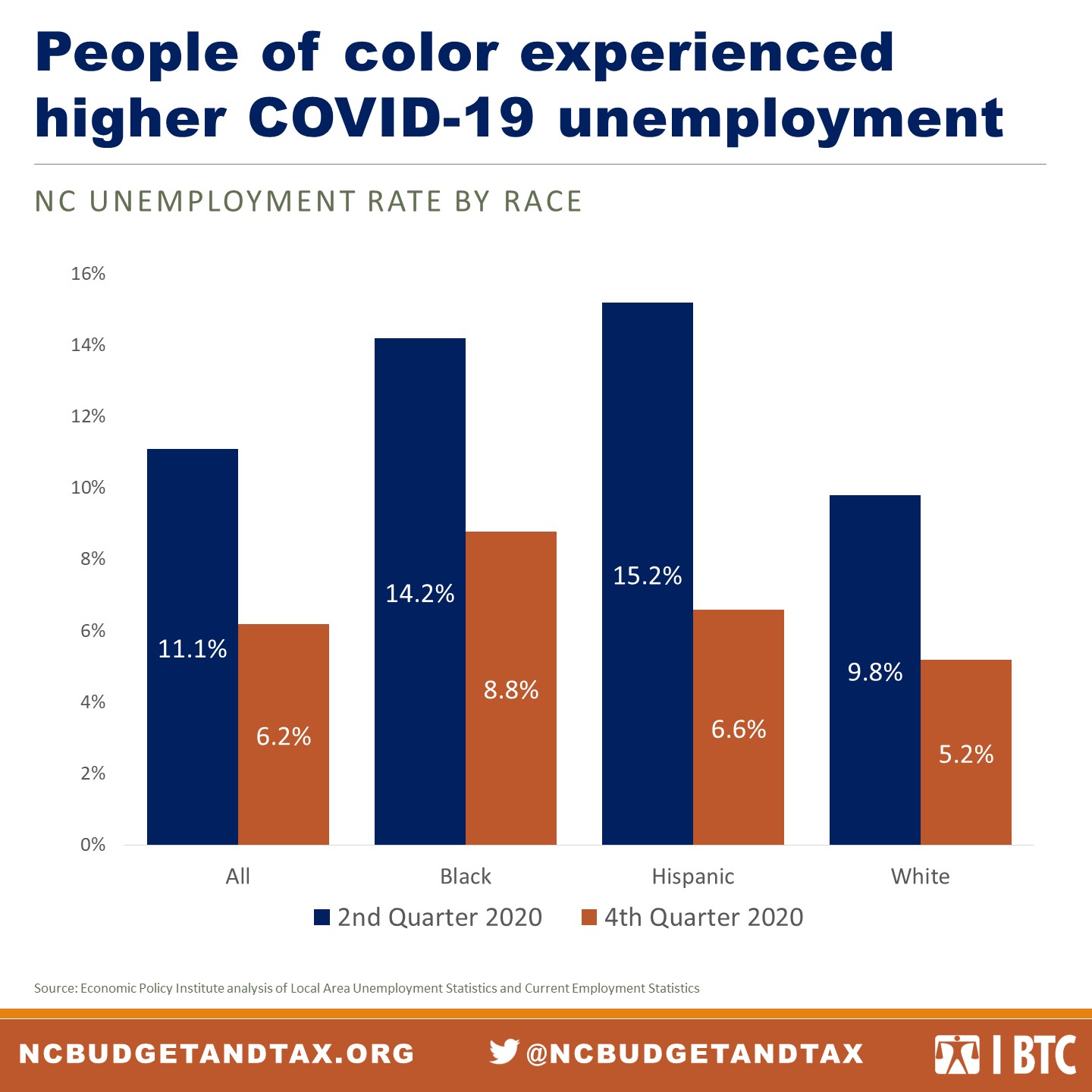

Recessions often hit hardest on people of color. Lack of access to careers that are more insulated from economic cycles, barriers to stable employment, and a host of other long-standing economic inequalities conspire to make recessions deeper and longer-lasting for working people of color. The COVID-19 recession is somewhat unique because people of color perform so much of the essential frontline work with increased risk of exposure to COVID-19, but the economic collapse still created higher levels of unemployment than for white North Carolinians.

- The initial wage of job losses during COVID-19 pushed Black unemployment above 14 percent and Hispanic unemployment above 15 percent, compared to less than 10 percent for white North Carolinians

- By the end of 2020, these disparities continued to exist with the white unemployment rate dropping to 5.2 percent, compared to 6.6 percent for Hispanic workers and 8.8 percent for Black North Carolinians.

Generations of rigging the game

Wage gains going to the top

Wage gains going to the top

A widening divide separates North Carolina’s best paid workers and everyone else. Wages for the bottom half of the workforce in North Carolina have been stagnate or even declined (adjusting for inflation) in recent decades, while the best paid employees have seen their earnings increase dramatically.

- The hourly pay different between the best paid 10 percent and the median wage in North Carolina has increased from roughly $14 in 1980 to over $26 in 2018.

- From the end of the Great Recession in 2009 through 2018, only the top 20 percent of North Carolinians saw their wage grow by more than $1 per hour, and 40 percent of working North Carolinians saw their real wages fall.

- Even with the best paid workers seeing big wage gains, the median real wage in North Carolina inched up by only 4 cents an hour in the decade from the end of the Great Recession through 2018.

Working people are getting more productive, but not seeing it in their paychecks

Working people are getting more productive, but not seeing it in their paychecks

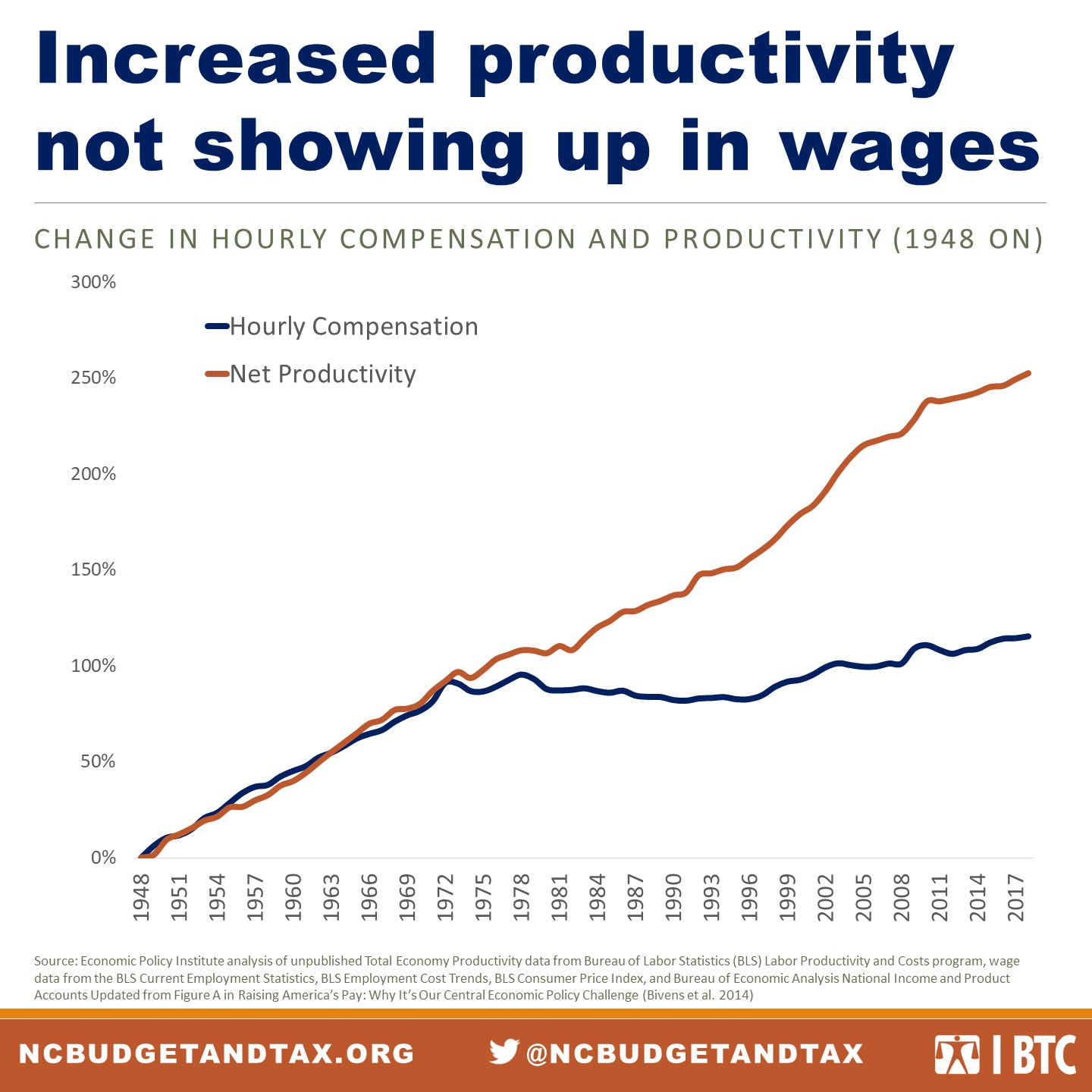

One of the core mechanisms of a healthy economy has broken down over the past 40 years in the United States. Increasing productivity is supposed to create better lives because each working person is able to produce more and grow the economic pie. U.S. workers are getting more productive, but they aren’t seeing it where it counts — in their paychecks.

- Between 1979 and 2018, worker productivity has grown by almost 70 percent, but real wages have only inched up by just 11.6 percent.

- Between 1979 and 2018, productivity grew more than six times faster than wages, creating huge wealth for a lucky few while most Americans did not see substantial improvement in their standard of living.

For the first few decades after WWII, innovation and education made U.S. workers more productive, and their wages grew right along, fueling the post-war economic expansion. A lot of workers, particularly white men in heavily unionized industries, were suddenly able to buy houses, go on vacations, and send their kids to college. Since the middle of the 1970s, it’s been a whole different story. American workers kept getting more productive, but the wealth they were creating increasingly ended up in rich peoples’ pockets and corporate balance sheets. By attacking workers’ power, empowering global corporations, holding down wages, and other tricks, special interests rigged the economic game to siphon off more of the wealth that our economy generates.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle