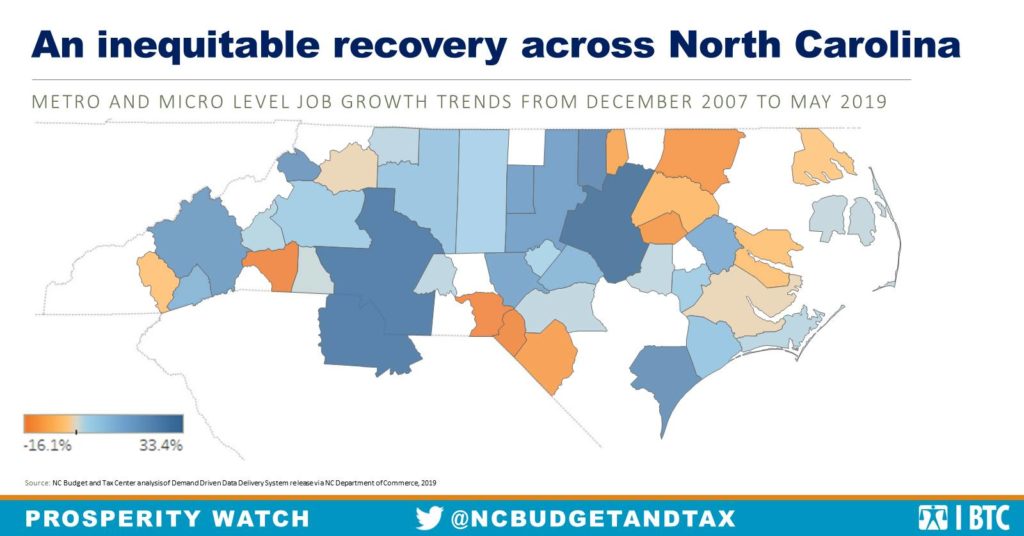

North Carolina’s general economic outlook has improved over the past 36 months, with labor force participation and the number of people employed trending upwards and the state’s unemployment rate dropping nearly 1 percentage point since May 2016. However, when parsing outcomes by region, it’s a very different picture. Metropolitan statistical areas (metros) like Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, Raleigh, Wilmington, and Asheville emerge as the drivers of the state’s recovery. These four metro areas have seen employment grow at least 20 percent since the beginning of the Great Recession. Conversely, micropolitan statistical areas (micros) in rural North Carolina like Cullowhee, Wilson, Roanoke Rapids, North Wilkesboro, and Laurinburg have been mired in a pattern of stagnant employment or actual loss of jobs.

There are 13 metro and micro statistical areas across NC that have lost jobs since the Great Recession, and North Wilkesboro and Wilson are examples of the cause for deep concern about the economic health of many local communities. Both micros have lost employment since the Great Recession while also losing jobs since last May. Not only has economic recovery eluded these communities, they’ve been hit with a double whammy of job loss over the past year in addition to never having returned to the level of employment from 12 years ago. Near the end of 2007 Wilson was a community of around 76,000 people with roughly 40,800 people participating in local labor market and over 38,400 of them employed. By May of 2018, Wilson had grown to nearly 81,500 residents but labor market participation had dropped to around 35,900 with 33,700 employed — while losing even more over the past year.

Wilson’s experience is disturbingly common as many communities across North Carolina that never recovered from the Great Recession have actually seen their local jobs picture worsen over the past year.

Large parts of northeastern and southeastern North Carolina have been forced to contend with similar economic conditions, with six micropolitan areas across the state experiencing more than a 10 percent drop in employment since the Great Recession.

The unbalanced recovery illustrated by labor market data proves that policymakers need to pay closer attention to the economies of rural and small-town North Carolina. The health of their Main Street businesses determines the quality of life for thousands of residents living outside the urban corridors along I-40 and I-85. Communities often shattered by natural disasters and economic shocks are clearly not receiving the support they need to rebuild and make progress.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle