HOW MUCH IS A LIFE WORTH? For families who suffer the loss of a loved one, the cost is incalculable, and the pain is especially great when their loved one dies on the job through the negligence or deliberate disregard of their employer. The NC Department of Labor (NCDOL), however, does attach a price tag to the lives of these workers who suffer death on the job—they calculate and levy penalties on those employers who violate basic workplace health and safety laws, including when those violations result in a fatality.

1. Introduction

When a laborer working for Delta Contracting was crushed to death between equipment and a retaining wall in a 2014 violation NCDOL labeled as Serious, the department decided that the laborer’s life was worth a penalty of $1,165.1

When a laborer died the same year getting trapped in cooling drums belonging to Gaston-based textile manufacturer Hi-Tex, Inc (another “Serious” violation), NCDOL did slightly better, levying a $13,000 penalty.2 However, the agency then dropped it to $4,000, suggesting perhaps that this laborer’s life was worth less at the end of the penalty process than at the beginning.

In the 2014 case of Powder Coating Services in Gaston, NCDOL found the company engaged in willful disregard for workplace safety, resulting in the death of a laborer who fell through a mezzanine due to negligent lack of safety equipment. Except that after completing the investigation, NCDOL agreed in a settlement that the violation wasn’t Willful after all and reduced the penalty from $50,100 to just $18,100.3

For most companies, such ultra-low penalties represent a mere slap on the wrist, and their ability to reduce these penalties even further during negotiations demonstrates a fundamental problem with the NCDOL’s ability to enforce the workplace laws that are intended to keep employees safe, healthy, and alive.

Unfortunately, these three examples above are not exceptional. A review of 60,653 state workplace violations over the past decade shows a clear pattern of inadequate NCDOL efforts to fully protect workers in the face of rising workplace deaths (see Appendix for the Methodology for this analysis). Specifically:

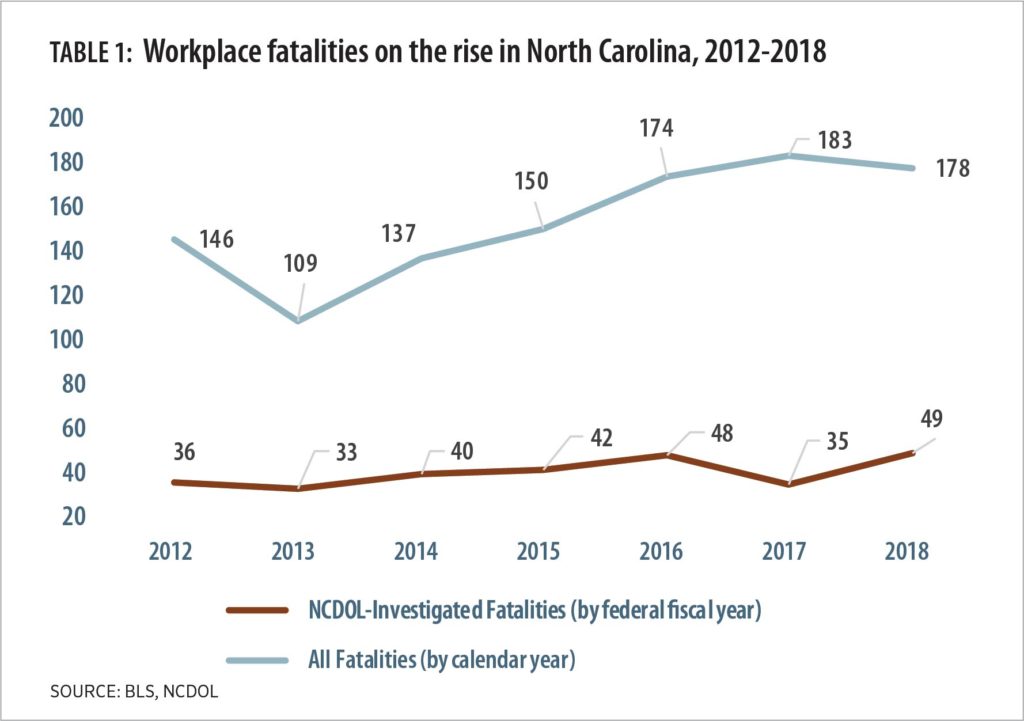

- Workplace fatalities have risen considerably in North Carolina, especially when compared to the national average. Since 2013, NCDOL has presided over a 48 percent increase in deaths on the job according to its own measure and a 63 percent increase according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.4

- NCDOL’s penalties are far too low to protect workers. The penalty system is designed to deter employers from putting their workers’ health and safety at risk. Yet, NCDOL routinely hands out exceptionally low penalties, especially when compared to the nation as a whole—and then routinely allows violators to negotiate their way to even lower penalties throughout the abatement process. Ultimately, many employers are paying pennies on the dollar for workplace violations that endanger workers’ lives, even in the cases where those violations

result in the deaths of their workers. - Enforcement of violations is too lax. NCDOL has also pulled its punches when it comes to levying the toughest violation standards against bad actor companies—the Willful violation, which OSHA defines as a violation in which the employer either knowingly failed to comply with a legal requirement (purposeful disregard) or acted with plain indifference to employee safety. NCDOL has handed out far fewer Willful violations than the national average and has significantly scaled back these assessments in fatality-related cases since 2013. In effect, NCDOL backed off full enforcement in almost two-thirds of the cases where workplace fatalities resulted from Willful violations.

- Investigations are too few. In the absence of workplace inspections, workers remain at risk—no one discovers health and safety violations until too late, often only after a catastrophe results in death or severe injury. Unfortunately, NCDOL is conducting too few investigations to meet the rising need. With a staff of just 97 inspectors in 2018, it will take 108 years to inspect every work site in the state, leaving the vast number of the state’s workers unprotected every year. Additionally, NCDOL has conducted fewer investigations of workplace incidents that result in fatalities or catastrophes requiring hospitalization (FATCATs), despite a significant rise in these incidents. This is likely due to the NCDOL policy decision to not investigate FATCATs involving independent contractors.

At the heart of the problem lies the core philosophy animating NCDOL’s enforcement efforts—the idea that workplace protections are best enforced through promoting voluntary compliance among employers, rather than aggressively using penalties and inspections to ensure employers follow workplace safety laws. In this laissez faire approach, NCDOL works to educate employers on worker protection standards, assists employers with compliance, and recognizes their good-faith efforts to improve workplace safety. In exchange for voluntary compliance, NCDOL offers lower penalties, laxer enforcement, and fewer investigations.

But the evidence is clear—this hands-off approach has not resulted in fewer workplace fatalities. Instead, workplace fatalities and incidents involving deaths or catastrophes have risen considerably, especially over the exact same years where fatality-related investigations, penalties, and Willful enforcement actions have waned most dramatically. Workers’ lives have intrinsic value, and NCDOL is not adequately protecting those lives in North Carolina. Instead, the agency should take steps to levy higher penalties, regularly enforce the Willful violation, and conduct more investigations, including in those cases involving independent contractors.

2. Workplace health and safety: an overview

The basic framework for enforcing workplace protections was created in 1970 with the passage of the Occupational Health and Safety Act, which created a new federal agency (OSHA) dedicated to protecting workers on the job from unsafe conditions. Over the 50 years of its existence, the agency has proved remarkably successful in improving worker occupational health and safety, bringing down the national workplace fatality rate from 11 deaths per 100 workers in 19705 to 3.5 today.6

North Carolina is a State Plan state. This means that US OSHA gives NCDOL the authority to administer health and safety enforcement activities with relative autonomy as long as the agency complies with basic standards and provides required annual reports on the state’s performance.

At the heart of OSHA’s enforcement framework lies a four-stage system that includes inspections, violation assessments, the levying of penalties on employers that violate state or federal workplace health and safety rules, and a long-running abatement process whereby violators can appeal their penalties. In the first stage, NCDOL proactively conducts a set number of “programmed” worksite inspections across the state every year using a random, computer-generated selection of employers in high-hazard industries that the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (NCOSH) has targeted through its Special Emphasis Program.7

The agency also conducts inspections in cases where a complaint of a serious hazard or violation has been lodged against a specific employer (usually by an employee), where previous violations require a follow-up visit, and incidents that resulted in the fatality or multiple hospitalization of workers (FATCATs). The agency also sometimes inspects after a reported amputation or overnight hospitalization of a worker.8

In the second stage of the OSHA enforcement system, NCDOL assesses whether the inspection or incident revealed any violations of state or federal safety standards. Violations are then classified according to OSHA definitions (see Box 1 for details).

Types of OSHA violations

OTHER-THAN-SERIOUS: A violation that has a direct relationship to job safety and health, but is not serious in nature, is classified as Other-Than-Serious. In 2019, the federally-mandated maximum penalty for each Other-than-Serious violations is $7,000.

REPEATED: An employer may be cited for a Repeated violation if the agency has been cited previously for the same or a substantially similar condition and, for a serious violation, state for federal OSHA’s regionwide inspection history for the agency lists a previous OSHA Notice issued within the past five years; or, for an Other-than-Serious violation, the establishment being inspected received a previous OSHA Notice issued within the past five years. In 2019, the federally-mandated maximum penalty for repeat violations generally start at twice the penalty of the original violation.

SERIOUS: A Serious violation exists when the workplace hazard could cause an accident or illness that would most likely result in death or serious physical harm, unless the employer did not know or could not have known of the violation. In 2019, the federally-mandated maximum penalty for Serious violations is $12,934, an increase from previous years.

WILLFUL: A Willful violation is defined as a violation in which the employer either knowingly failed to comply with a legal requirement (purposeful disregard) or acted with plain indifference to employee safety. In 2019, Willful violations have a federally-mandated maximum penalty of $132,598 per violation.

It is unclear whether NCDOL has adopted any of the federal maximus, which were raised in 2016. The NCDOL program manual lists minimum penalties but is silent on the new maximums.9

Source: Federal Employer Rights and Responsibilities Following an OSHA Inspection10; and OSHA Penalties.11

In the third stage of the OSHA enforcement framework, NCDOL assesses the penalties employers should pay for each violation, using the statutory maximums for each violation type as a guide (see Box 1). In both the second and third stages, NCDOL exercises considerable discretion in determining the Violation Type and Penalties for violators, and these initial assessments are often the product of informal, behind-the-scenes negotiations with employers before these initial rulings are even issued.

Once rulings are issued, the fourth stage of enforcement begins—the abatement process, where violators can appeal both the Violation Type and the associated penalties. NCDOL often agrees to settle these cases for significantly lower penalties or to reduce the Violation Type (e.g., from a Serious to an Other-than-Serious). Under OSHA statutes, employers also have the right to further appeal their cases to an Administrative Law Judge, where attorneys with the NC Department of Justice must defend NCDOL’s initial assessments. The U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee found through extensive testimony and investigations that labor enforcement agencies (in this case, NCDOL) often face significant pressure throughout this process to retreat from their initial assessments, reach early settlements with employers that favor these violators, and offer only tepid defenses in appeal cases before Administrative Law Judges12. As a result, the abatement process significantly reduces violators’ costs for placing their workers’ lives at risk with a high level of frequency.13

From this, it is clear that NCDOL exercises a high level of discretion over its enforcement efforts, and that violators have many opportunities to reduce the costs of their bad behavior if NCDOL chooses to let them off lightly. In doing so, however, weak enforcement undermines the foundational principle of the landmark OSHA law—that a strong enforcement regime deters employers from placing their employees’ health and safety at risk.14 The main point of OSHA is to use enforcement to deter corporate bad behavior and save lives on the job. Without aggressive inspections and appropriately strong penalties, it is unclear what will keep employers from playing fast and loose with their employees’ lives in order to keep their costs down and their margins up in the face of stiff global business competition. This, after all, is why the Nixon Administration enacted OSHA—because the absence of workplace protections resulted in high numbers of workplace deaths.

Despite the crucial role of enforcement as a deterrent, NCDOL follows a much different philosophical approach. In recent years, NCDOL has embraced the idea that workplace protections are best enforced through promoting voluntary compliance among employers, rather than aggressively using penalties and inspections to ensure employers follow workplace safety laws. In this hands-off approach, NCDOL trains employers on workplace health and safety standards, assists them with complying with these standards, and rewards their efforts through their inclusion in recognition programs, like the Carolina Star program and the Safety Awards Program. In exchange for voluntary compliance, NCDOL offers a much lighter touch in terms of enforcement.

Unfortunately, NCDOL’s approach fails to hold up under examination. As seen in the following sections of this report, NCDOL’s voluntary compliance approach has failed to adequately protect workers, reduce the workplace fatality rate, or deter bad actors from placing their workers’ lives in danger on the job. NCDOL’s penalties are too low, its enforcement too lax, and its investigations too few.

3. Portrait of the fallen

In North Carolina, as across the country, the workers most likely to die on the job are always the most vulnerable and marginalized. Unfortunately, the numbers are growing. The exact number of workplace fatalities depends on who is doing the counting. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) includes everyone who dies on the job in the state, while NCDOL only counts some of them. Specifically, North Carolina’s labor agency does not count anyone covered by federal OSHA, and, critically, independent contractors. While the number of people employed at federally-covered businesses (the maritime industry and federal agencies, for example) is a relatively small portion of the state’s overall employment base, the number of independent contractors is growing (see section 6).

Regardless of who is doing the counting, workplace fatalities have risen considerably over the past five years in North Carolina—a 48 percent increase according to NCDOL and a 63 percent increase according to BLS (see Table 1). However, since NCDOL does not investigate independent contractor fatalities, the actual number of workplace fatalities is likely significantly higher than the number NCDOL is claiming.

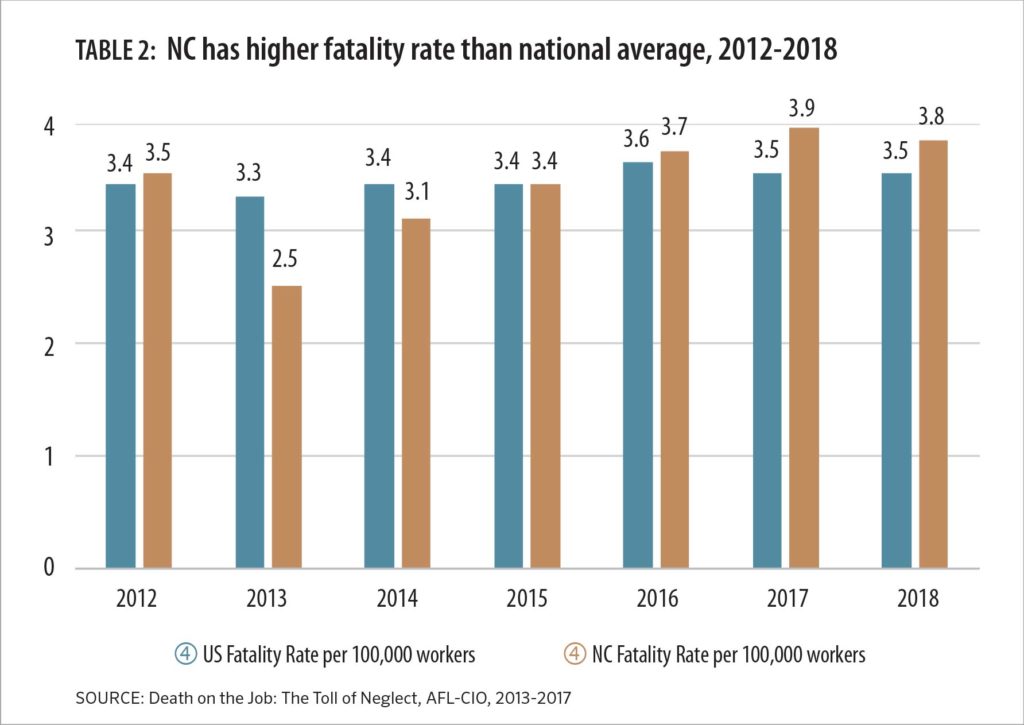

Not only are workplace fatalities rising year over year, they’re also going up compared to the nation as a whole. Five years ago, North Carolina had a lower workplace death rate—the number of deaths per 100,000 workers—than the nation on average. Yet while the national average has basically remained steady in the years, North Carolina’s workplace fatality rate has exploded—from 2.5 in 2013 to 3.8 in 2018 (see Table 2).

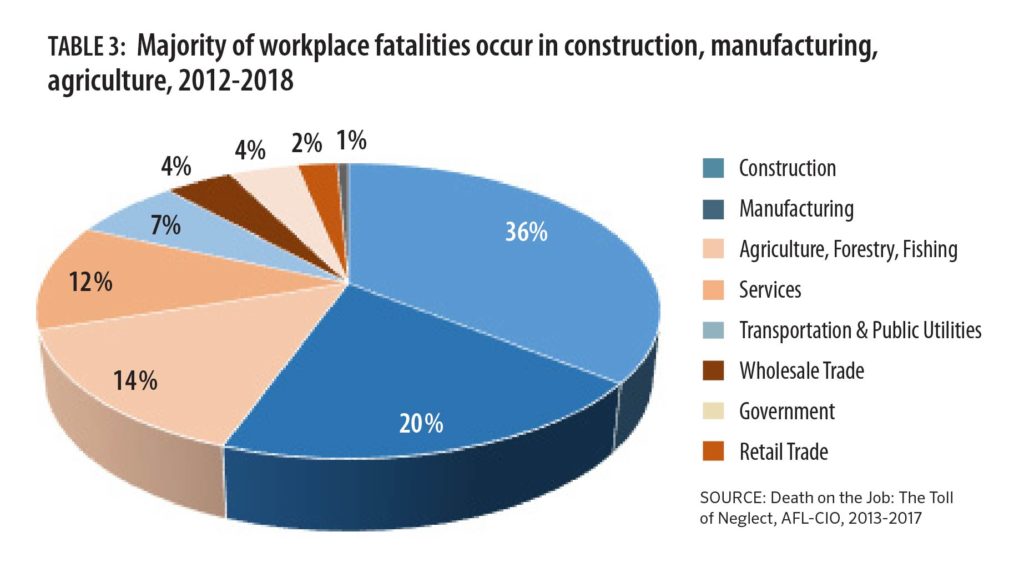

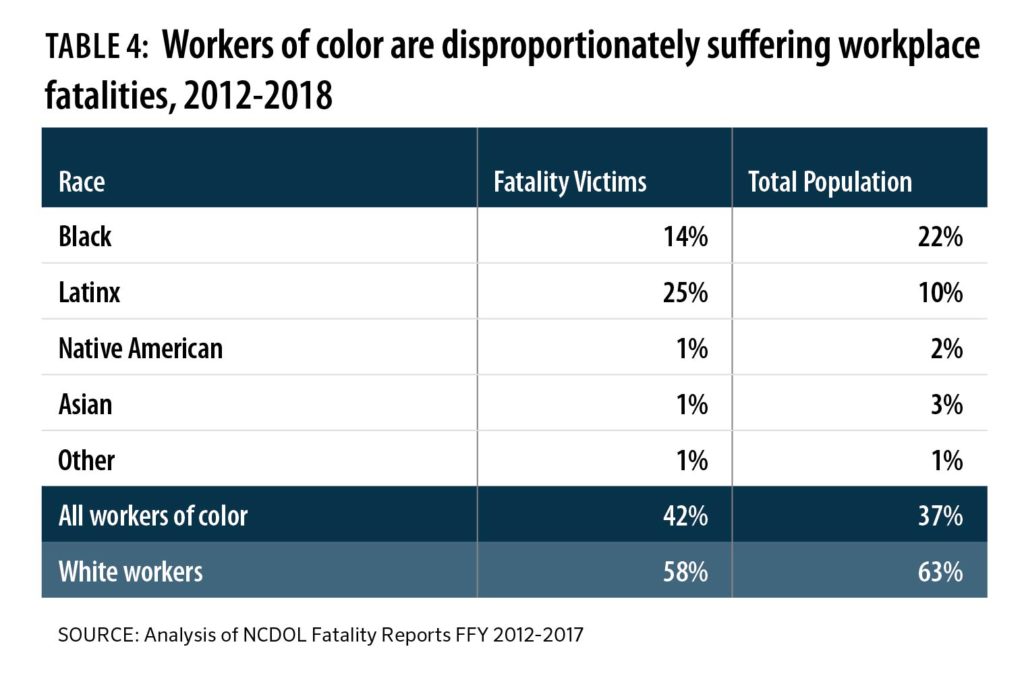

The risk of dying in the job depends heavily on the industry where someone works. Seven out of every 10 workplace fatalities happen in just three industries—construction, manufacturing, and agriculture (see Table 3). Given this industry mix, workers of color—particularly of Latinx descent—are dying on the job at a disproportionately higher rate compared to their population numbers. As seen in Table 4, workers of color comprised about 37 percent of North Carolina’s population in 2018 but constituted 42 percent of the workplace fatalities. This is driven largely by Latinx workers who are over-represented in construction (which suffers the highest fatality rates) and account for 25 percent of workplace fatalities compared to just 10 percent of the population. In contrast, white workers make up 63 percent of the total population, but only a little more half of the state’s workplace fatality victims. From these numbers, it is clear that workers of color face much higher exposure to the possibility of death on the job than white workers, largely because they are disproportionately concentrated in the most high-risk industries.

Despite these troubling trends, NCDOL’s workplace protections appear ineffective at bringing down the fatality rate—penalties are too low, enforcement is too lax, and investigations are too few to adequately protect employees’ health and safety on the job.

4. Penalties are too low

NCDOL’s penalties are far too low to protect workers. The core system for enforcing workplace protections—and deterring workplace fatalities—involves the levying of penalties on companies that are found by the NCDOL to have committed workplace health and safety violations. The more serious the violation by an employer, the higher the penalty the violator should pay. In theory, higher penalties should deter employers from putting their employees at risk.

But for the theory to work, penalties need to be high enough to disincentivize employers from cutting corners and putting their employees at risk—the cost of paying OSHA penalties needs to be higher than the cost of complying with workplace safety standards. Unfortunately, that theory rarely translates into reality in U.S. workplaces, where most labor violation penalties are a few thousand dollars at most and often amount to nothing at all.

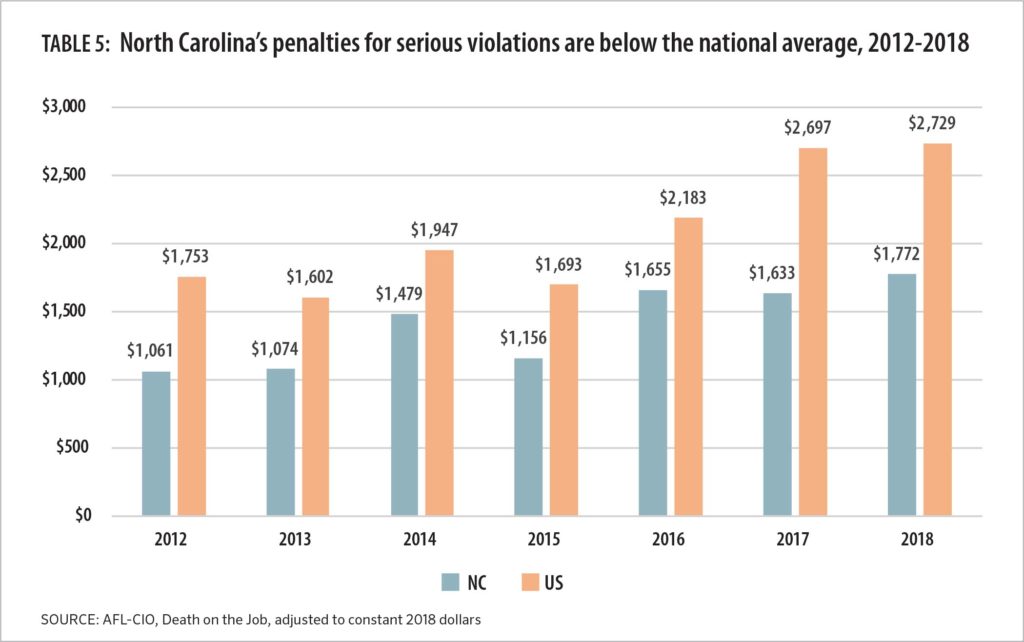

In the case of North Carolina, NCDOL routinely hands out exceptionally low penalties and then allows violators to negotiate their way to even lower penalties throughout the abatement process. Ultimately, many employers are paying pennies on the dollar for workplace violations that put workers’ lives and limbs at risk. As seen in Table 5, NCDOL has levied penalties for Serious violations that are a fraction of the national average every year since 2012—on average, North Carolina’s fines were more than 30 percent below the national average for Serious offenses.

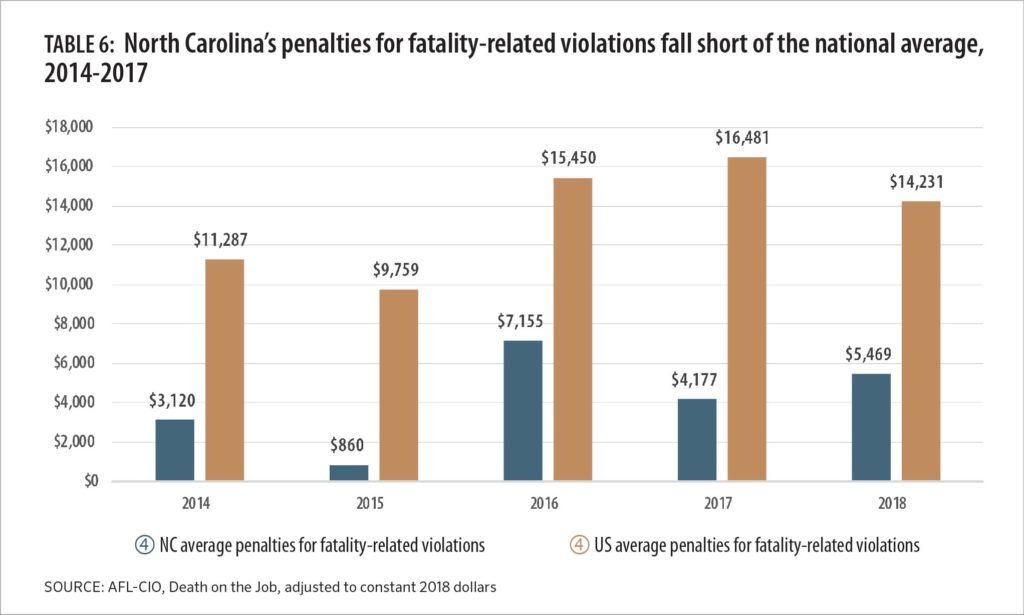

More troubling is NCDOL’s record with fatality-related penalties, specifically. Since 2014 (the first year data is available), NCDOL has assessed penalties involving fatalities that are 70 percent below the national average—and getting worse. In 2014, for example, NCDOL levied an average of $3,120 in penalties on violations involving workplace deaths, while the national average was $11,287—a 72 percent gap. By 2017, that gap had grown to 75 percent, with NCDOL penalizing these violators an average of $4,177 compared to the national average of $16,481.

As if low initial penalties were not bad enough, NCDOL is also allowing bad actor violators to lower them even further through the abatement process. Of the 170 fatality cases since 2012 where data was available, NCDOL gave these bad actor violators a combined $433,423 discount (in 2018 constant dollars)—an average write-down of $2,535 per death15. With these ultra-low penalties and big penalty reductions, it is no surprise that workplace fatalities have continued to rise.

5. Enforcement is too lax

NCDOL has also pulled its punches when it comes to levying the toughest violation standards against bad actor companies—the “Willful” violation, which OSHA defines as a violation in which the employer either knowingly failed to comply with a legal requirement (purposeful disregard) or acted with plain indifference to employee safety.

The Willful finding affects violators in two main ways. First, they face a much higher maximum penalty. Prior to an Obama Administration policy change in 2016, the maximum penalty for a Willful violator was $70,000 per offense. Since then, the maximum has been raised to $126,000 and then adjusted for inflation every year thereafter (the new maximum in 2019 is $132,598 per violation)16. This compares to the maximum $7,000 penalty (pre-2016) and $12,600 plus inflation (post-2016) for Serious violations, so companies incur considerably larger financial costs for a Willful violation than a finding of other lesser offenses. Secondly, Willful violations keep companies from membership in voluntary health and safety compliance recognition programs like Carolina Star. These are the two big sticks OSHA uses when they deploy a Willful finding, and both are intended to deter companies from putting their employees’ health and safety at risk. As a result, Willful violations are a key tool in reining in workplace fatalities.

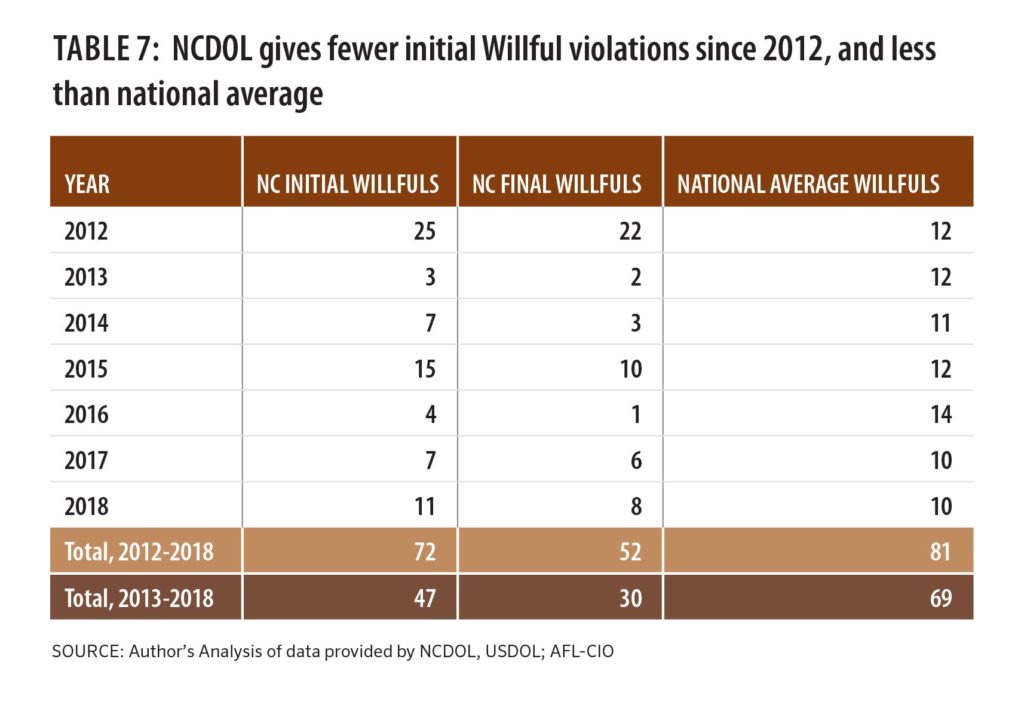

Unfortunately, NCDOL is giving out too few “Willful” violations—and giving out fewer over time. In 2012, NCDOL gave 25 initial “Willful” violations to bad actor employers—the highest number at least since 2003. But in subsequent years, the agency backed down considerably in levying this violation. By 2018, this number fell to just 11 (see Table 7).

NCDOL also falls short compared to the national average. Between 2013 (the year after NCDOL’s high-water mark) and 2018, there were 69 combined Willful violations issued by Federal OSHA and the states with state administered health and safety plans—in contrast, NCDOL issued a total of 46 (see Table 7). Moreover, North Carolina has assigned fewer initial violations of this type than the national average in four out of the last six years.

But NCDOL’s lax enforcement isn’t just measured by levying too few Willful violations—it’s also obvious in how often the agency negotiates away the ones they do initially hand out. Since 2012, NCDOL has given companies a total of 71 Willful violations, yet they negotiated away 20 of those findings (28 percent) during the settlement and abatement process. Once these “ghost Willfuls” are taken into account, North Carolina’s enforcement numbers look even more disconcerting for the health and safety of its workforce, dropping to a total of just 51 since 2012, compared to the national average of 81. Moreover, once we look past NCDOL’s 2012 heyday, the numbers get even worse—NCDOL has backed off so much on enforcement that other states have handed out almost two-and-a-half times the number of Willful violations (69) as NCDOL issued since 2013.

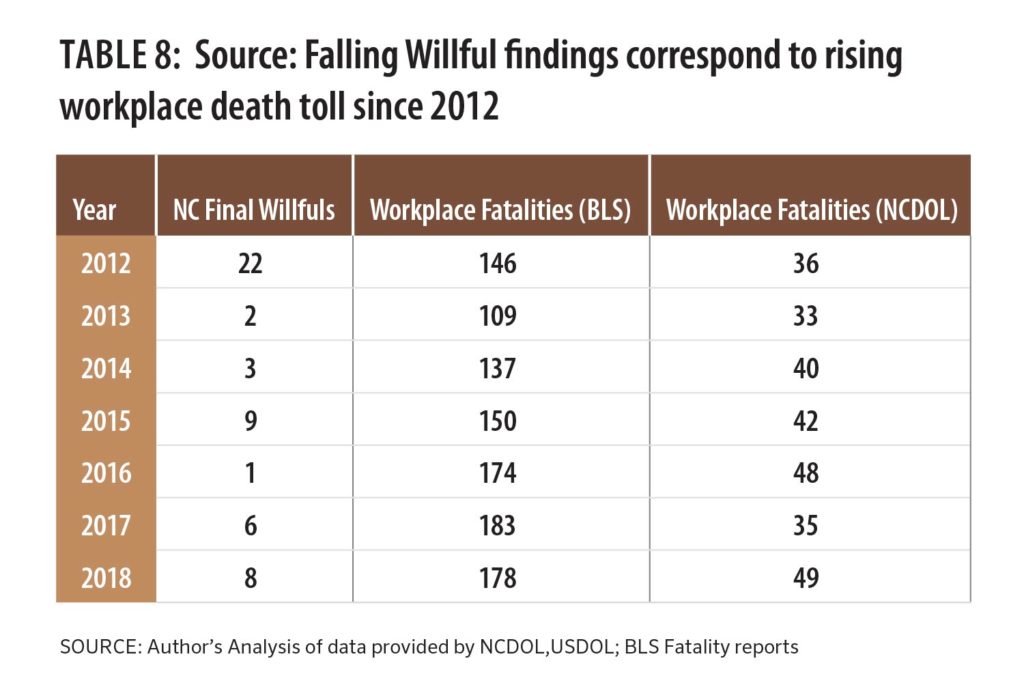

Tragically, the significant decrease in Willful violations corresponds to an equally significant increase in fatalities over the same time period, according to both state and federal counts. This reinforces the importance of this violation in particular as a deterrent to the purposeful disregard for employee health and paints a bleak picture for workplace safety if NCDOL is unwilling to use it when needed.

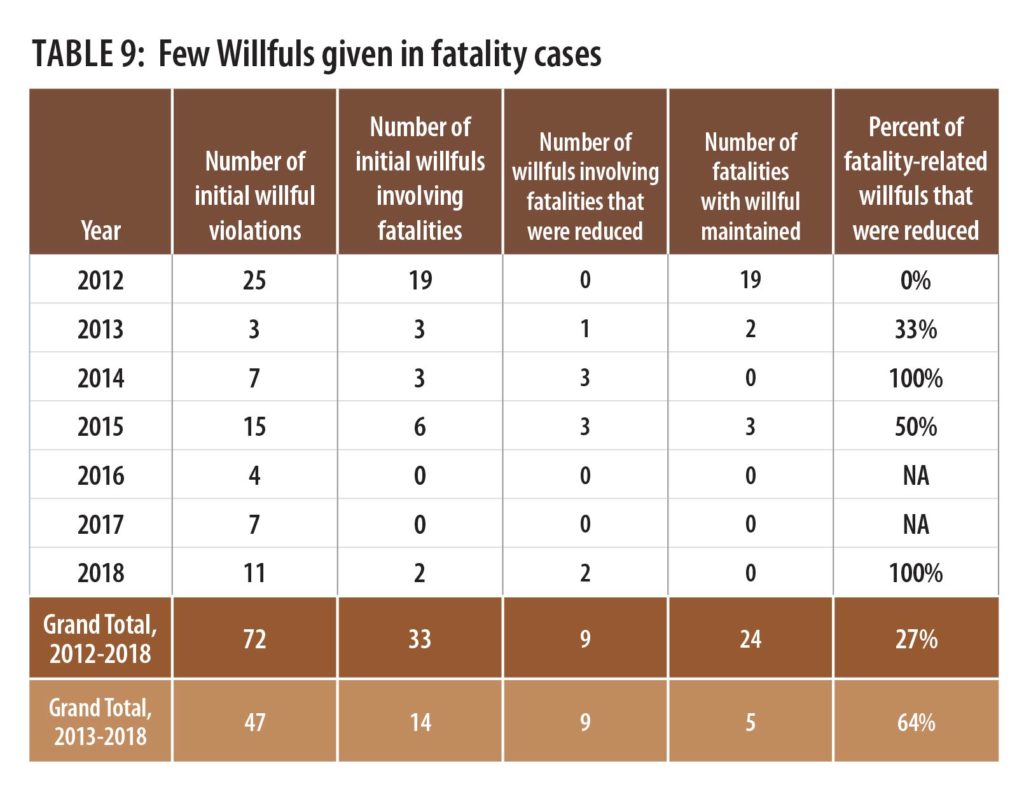

Not only is NCDOL failing to enforce “Willful” violations, the agency is especially lax when it comes to holding violators accountable in fatality cases. Just as overall Willful violations are down, their use in fatality cases has also dropped precipitously, from 19 in 2012 to just two in 2018. And there were no Willful violations given out at all in 2016 or 2017 in fatality-related cases, despite the overall spike in workplace fatalities in those years.

But as with the overall Willful numbers, fatality-related Willful cases also saw significant renegotiation and retreat by NCDOL after the high-water mark in 2012—on nine occasions since 2013, the agency reduced its initial “Willful” finding to something less onerous during the settlement and abatement process. Given that there were only 13 fatality-related Willful findings to begin with, this means that NCDOL backed off its enforcement in more than two-thirds of the relevant cases.

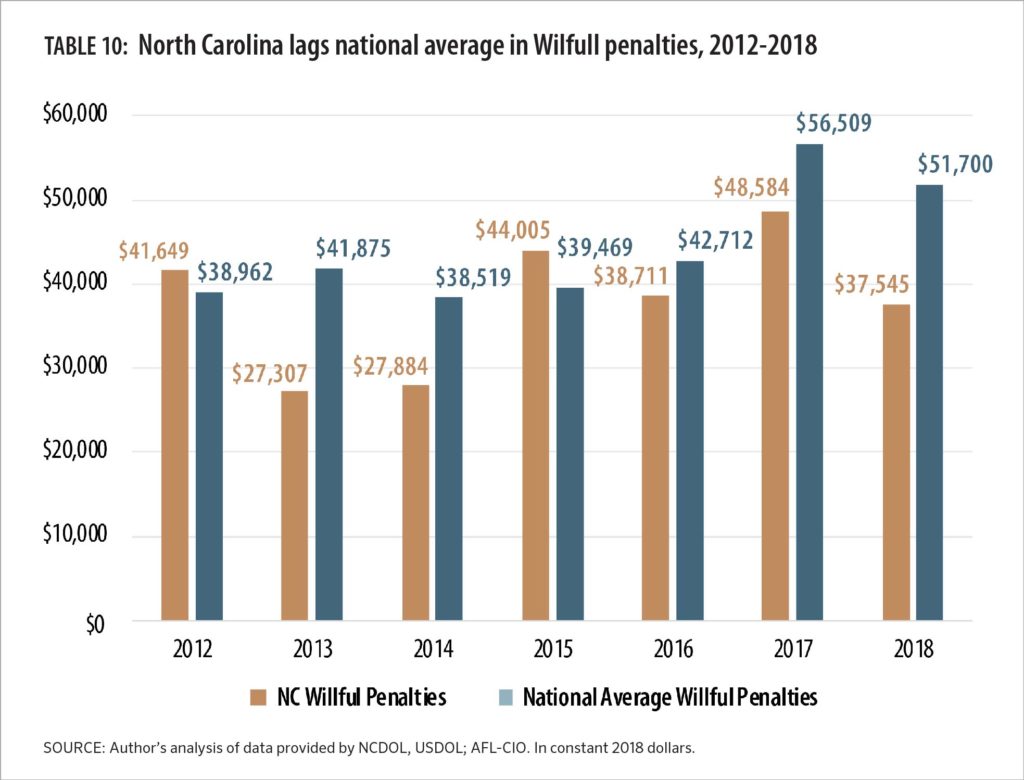

Penalties tell a similar story of lax enforcement with Willful violations. As seen in Table 10, NCDOL’s initial penalties for these violations fell significantly below the national average for sites inspected by federal OSHA and states with state-administered OSHA plans. In 2018, NCDOL initially handed out $37,500 (in 2018 dollars) to Willful violators, compared to the national average of $51,700. The story is similar going back to 2012—in only two of the past six years did NCDOL’s Willful penalties exceed the national average, one of them being the high-water year of 2012.

NCDOL also falls short on Willful penalties in a second way. In 2016, the Obama administration increased the maximum penalty for Willful violations from $70,000 to $126,000. As Table 10 makes clear, NCDOL’s average Willful penalties were never close to the maximum, either before or after Obama’s policy changes. In fact, NCDOL only handed out the maximum 11 times between 2012 and 2018—and in seven of those the agency ended up reducing the penalty to far below the legal max. Taken together, NCDOL reduced “Willful” violation penalties by almost $800,000 (in 2018 dollars) between 2012 and 2018—a reduction of almost 30 cents on every dollar in penalties.

One likely culprit behind the low penalties and the lack of Willful violations is the NCDOL practice of interviewing workers in front of their managers, in contrast to the U.S. OSHA practice of conducting inspection interviews in private. The NCDOL approach virtually guarantees a climate of fear in which workers will not feel free to share the real health and safety problems on the worksite for risk of being fired.17

The Willful violation provides a very useful report card for NCDOL’s health and safety efforts—and from the low number handed out to their constant reduction, to the ultra-low penalties—on every count, NCDOL is clearly too lax on enforcement.

6. Investigations are too few

NCDOL is also falling short by conducting far too few investigations to adequately protect the lives of working people in North Carolina. In the absence of workplace inspections, workers remain at risk—health and safety violations remain uncorrected until too late, often only after a catastrophe results in death or severe injury. Unfortunately, NCDOL is conducting too few investigations to meet a rising need.

Part of the problem is a crippling lack of inspectors. In federal fiscal year 2019, NCDOL used 97 inspectors—two associated with Federal OSHA and the rest working for NCDOL. This translates to one inspector for every 44,645 employees and every 2,531 establishments, nowhere near enough to provide adequate coverage. In fact, the AFL-CIO estimates that it would take 108 years to inspect every workplace in North Carolina just once with the current number of NCDOL inspectors.18 Without inspections, it is impossible to ensure businesses are following health and safety laws and protecting the lives of their employees.

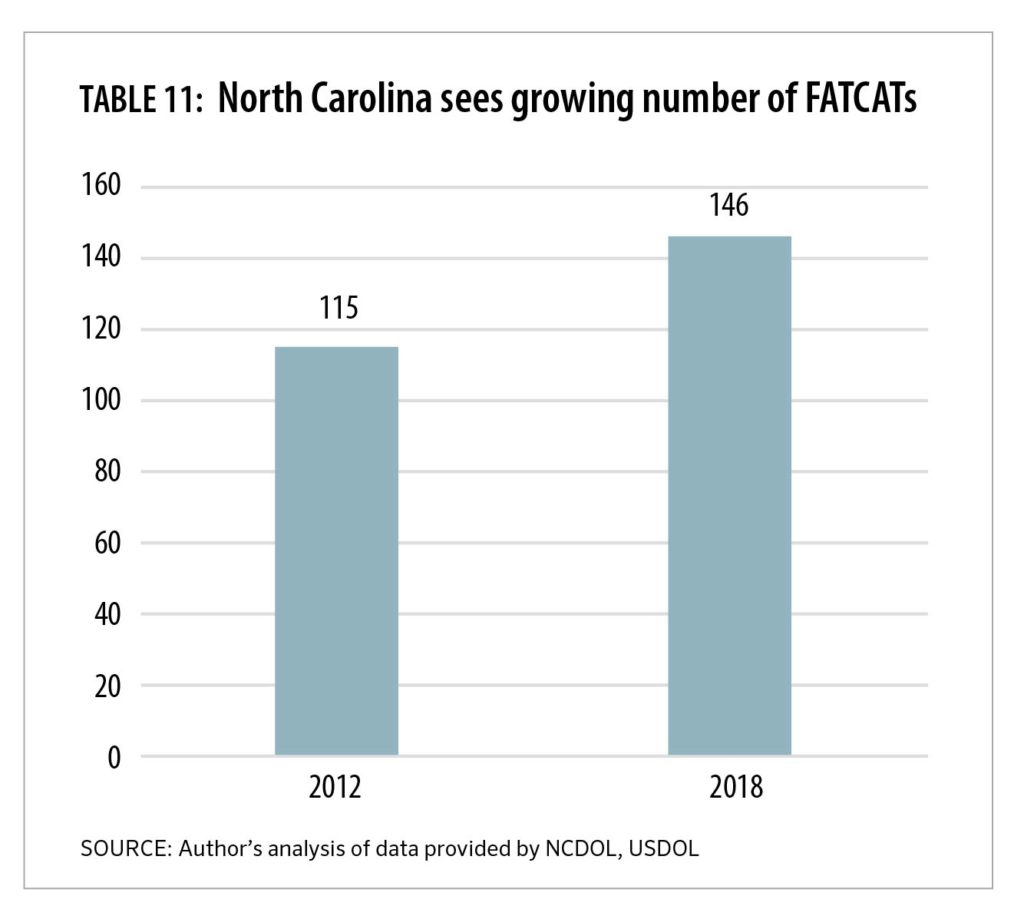

At the same time, the need for more inspections is rising. As we’ve seen, NCDOL-covered workplace fatalities rose from 36 in 2012 to 49 in 2018, and in addition, the number of workplace incidents that involved a fatality or a catastrophe (in which multiple workers are severely injured and hospitalized) also saw a significant jump, from 115 in 2012 to 146 in 2018 (see Table 11). These trends suggest the need for more inspectors to conduct more inspections of more workplaces.

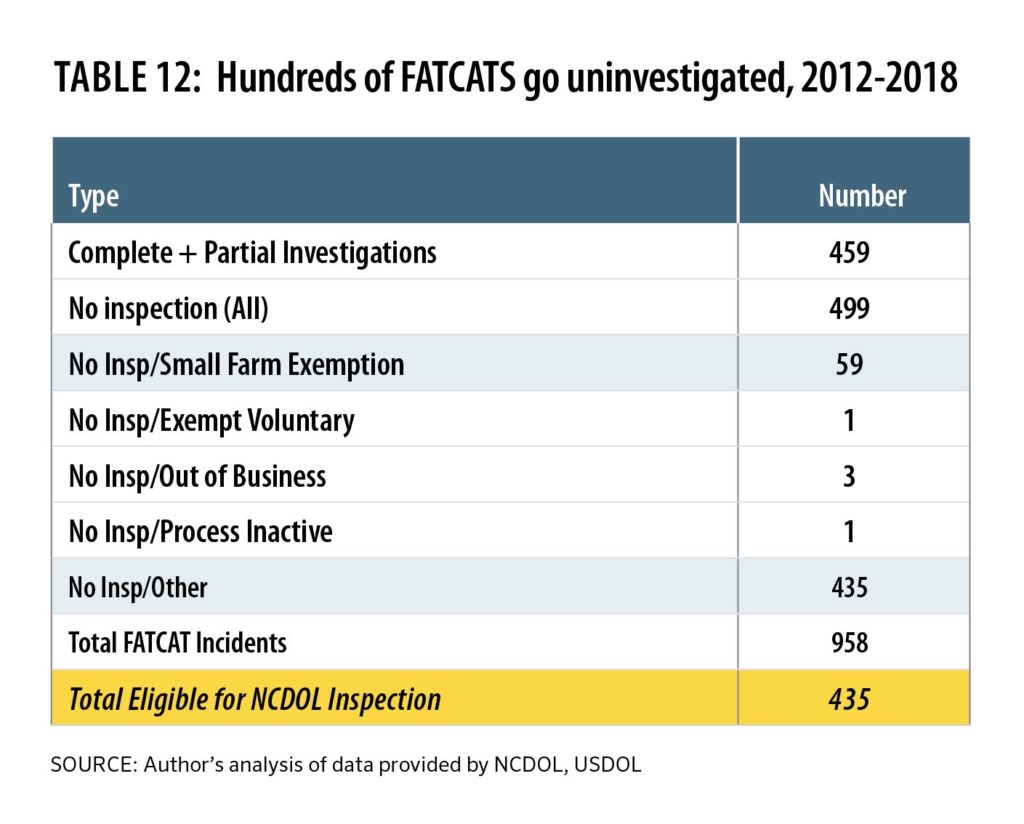

Yet despite the growing need, NCDOL has conducted fewer full investigations of FATCATs than in past years and has abandoned an increasing number of these cases without conducting a serious inspection at all. Over the past seven years, a total of 958 FATCATs were reported to NCDOL, of which a little less than half (459) received a partial or full inspection. In “complete” inspections, NCDOL was able to expand the scope of a FATCAT inspection to include other observable violations, while in a “partial” inspection, the agency was only able to inspect conditions related to the fatality itself. In both cases, however, inspections actually occurred, and a number of these cases are still ongoing in the settlement and abatement process.

This stands in stark contrast to the 499 cases where an inspection did not occur at all. As seen in Table 12, the two largest categories of non-inspected FATCATs involve Exemption by Appropriations Act and an innocuous-sounding “Other” category. Both categories reveal a clear pattern of NCDOL failing to fully investigate catastrophic workplace incidents resulting in the deaths or hospitalizations of workers on the job.

By way of context, exemption by Appropriations Act only applies to small farms (e.g., fewer than 10 employees) with no temporary migrant labor camps located on the premises or to employers with fewer than 10 employees in certain federal OSHA designated low-hazard industries. Since 2012, NCDOL has not conducted a FATCAT-related inspection in 59 of these cases, including 10 incidents involving farms and 49 involving low-risk industries.

At first glance, it appears reasonable that NCDOL did not perform an inspection in these 59 cases, yet a deeper look raises several areas of concern that call into question whether the agency went as far as it could or should have in investigating the deaths and hospitalizations of these people.

First, in the case of the farms, NCDOL is only exempted from using federal funds to inspect these sites, so it is curious that the agency also refused to use state-appropriated OSHA funds to carry out inspections in these cases, even when such action is clearly permissible under North Carolina’s state plan. Workplace deaths and catastrophes should be the first priority for engaging in state-funded health and safety enforcement activities.

A second area of concern surrounding Appropriations Act exemptions involves the OSHA designated low-risk industries. All 49 of these un-inspected FATCAT incidents occurred since 2015, when U.S. OSHA released updated instructions on inspections involving these exemptions. The new update specifically states that (emphasis added):

“The reporting requirements of 29 CFR 1904.39 changed effective January 1, 2015. Employers are obligated to report to OSHA incidents involving a fatality, the in-patient hospitalization of one or more employees, an amputation, or the loss of an eye. OSHA is allowed to inspect or investigate an incident involving a fatality of one or more employees or the hospitalization of two or more employees of a small, non-farming employer once we become aware of the incident.”19

Under this guidance, NCDOL is not prohibited from conducting an inspection of these workplace deaths and catastrophes. As with the permissible use of state funds for inspections of small farms, it raises serious questions about why NCDOL is failing to use these tools to investigate workplace deaths and keep workers safe on the job.20

Beyond these exemptions, another group of FATCAT incidents went uninspected and were given the non-specific designation No Inspection/Other. As a matter of policy, NCDOL does not conduct an inspection when a preliminary investigation reveals the cause of the fatality was not work related (it may be due to natural causes—say, a heart attack on the job), or when there is a fatality not covered by OSHA, such as a traffic accident (a Wal-Mart employee is struck by a car in the parking lot). Indeed, traffic accidents are the single largest source of workplace deaths across the nation, accounting for about 40 percent of all workplace fatalities, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Yet traffic accidents cannot account for all FATCAT incidents that went uninspected. Taken at face value, there were 436 FATCATs that were reported to OSHA and eligible for investigation but where NCDOL did not conduct an inspection following the fatality (we also included the single case when no inspection occurred because the inspection process went inactive). See “No Inspection/Other” and No Inspection/Inactive” in Table 12 for details.

The problem, however, is that it remains impossible to assess how many FATCATs went uninspected because of understandable deaths by natural causes or traffic and how many went uninspected because NCDOL simply chose not to pursue a full inspection. If North Carolina follows the national average in terms of traffic-related workplace deaths, this could account for about 174 of the total uninvestigated FATCATs (40 percent of the 436 incidents that could have been investigated). However, it cannot account for the remaining 262 cases, so the question remains why these cases are going uninspected.21

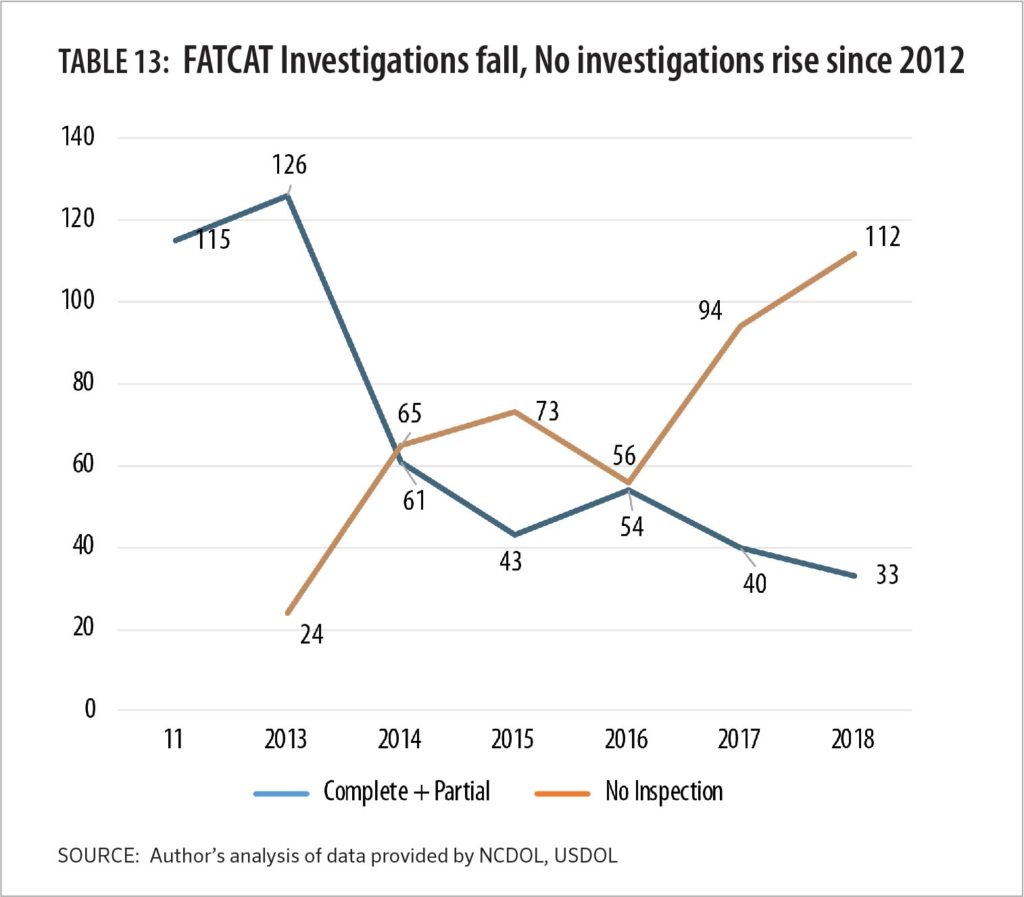

What is clear from the data is that the number of regular inspections fell precipitously (from 102 in 2012 to just 33 in 2018) at the same time as the number of uninvestigated FATCAT cases skyrocketed from 11 in 2012 to 112 in 2018 (see Table 13)—a trend particularly pronounced starting in 2016.

This follows the same trend of declining enforcement post-2012 seen with Willful designations and penalties. Although it is impossible to say with certainty without seeing case-specific data for each FATCAT, this pattern of inspections raises critical concerns about whether NCDOL is truly investigating these fatalities/catastrophes as thoroughly as it should—especially against the broader backdrop of NCDOL’s overall lax enforcement after 2012.

If the decisions to not investigate FATCAT incidents were solely due to deaths by natural cause or traffic accidents in parking lots, one would expect the total number of investigations to remain largely constant, with maybe a slight uptick after 2014 to account for an improved economy employing more people and engaging more customers, thus creating more opportunity for accidents. Yet this represents a 900 percent increase in uninvestigated FATCAT cases, and it appears highly unlikely that increases of this magnitude are due solely to deaths by heart attacks on the job or unavoidable traffic accidents in Wal-Mart parking lots—especially since the trend is coupled with the 68 percent reduction in partially/completely investigated cases over the same period.

Instead, it looks like NCDOL policy decisions are responsible for declining inspections. One possible explanation is the agency’s refusal to conduct any investigations of FATCATs involving potentially misclassified workers. State and federal OSHA laws only cover those workers classified as “employees”—they have a standard employee-employer relationship, where the employer controls the day-to-day activities of the employee in exchange for wages and benefits. Unfortunately, North Carolina and the nation at large have seen an explosion in misclassification, which occurs when an employer improperly labels workers as independent contractors when they are actually employees.22

In practice, misclassification looks like an employer controlling the day-to-day work activities of the worker over an indefinite and ongoing period of time in the same way it would for an employee, but then calling the worker an independent contractor in order to avoid covering them on workers compensation and unemployment insurance.23 Since misclassified workers are independent contractors and not “employees,” NCDOL does not investigate the workplace incidents (including FATCATs) that involve these workers. Perversely, this gives employers an added incentive both to misclassify their workers on an ongoing basis and to mis-report their employees’ status as contractors when notifying NCDOL of a workplace fatality.

While NCDOL cannot directly conduct health and safety inspections that involve independent contractors, the agency does have the authority and responsibility to investigate misclassification. There is nothing that would prevent the agency from opening misclassification investigations into those FATCAT cases where employers report independent contractors were involved. As part of this investigation, NCDOL inspectors could also evaluate the surrounding workplace conditions for violations, including those involving the FATCAT incident.

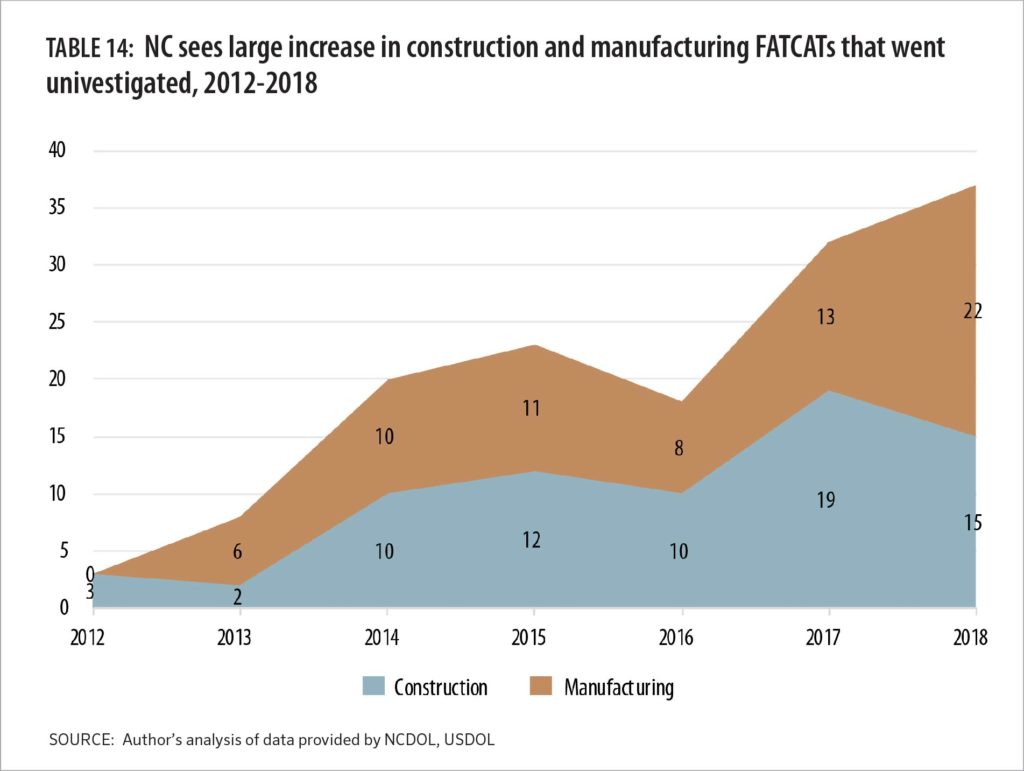

It is likely that misclassification is at least in part driving these uninspected FATCATs. First, across the country, states have averaged about 21 independent contractor deaths per year since 2012. If North Carolina has been no better than the national average, then we could expect that independent contractor deaths can account for at least 147 of the total uninvestigated FATCATs over the past seven years. And that number is likely higher because North Carolina has significantly greater population than the national average. Nonetheless, the independent contractor death toll reflects high levels of misclassification because they are concentrated in the industries that research has found to most suffer from misclassification across the country and in North Carolina specifically—notably, construction, and manufacturing.24 As seen in Table 14, these industries have seen double-digit increases in uninvestigated FATCATs, the largest growth out of all the sectors in the economy.

Without case-specific data, it is impossible to know for certain, but it is entirely reasonable based on publicly available FATCAT data to conclude that misclassification and NCDOL’s blanket refusal to investigate fatalities reported by companies involving so called ‘independent contractors’ are drivers for both the rise in fatality-catastrophe incidents in these industries and the overall decline in FATCAT investigations. Unfortunately, NCDOL does not make this data publicly available, either through its reports to federal OSHA or in the fatalities data on its website.

Even if these trends are entirely innocent and indeed due to heart attacks and bad parking lot site design, they still speak to NCDOL’s inability or unwillingness to conduct enough investigations to meet the growing need and keep up with rising deaths on the job. At the very least, as long as fatalities and FATCAT incidents are increasing, it doesn’t make sense to scale back inspections or rely on a pool of inspectors so small that it will take more than a century to inspect every workplace in the state.

In addition, there is no reason why NCDOL cannot use its platform to convene stakeholders to address problems like workplace traffic deaths. For example, North Dakota saw an explosion in workplace traffic deaths in the past decade, and since state OSHA could not investigate, federal OSHA stepped in to study why so many accidents were happening. The problems turned out to be related to fracking transportation, and this led to a strong inter-agency effort at the state level to improve training for fracking-related truck drives and improved signage and transportation accessibility at fracking sites. Examples like this demonstrate how NCDOL could lead rather than follow on keeping people safe on the job.

7. The shortcomings of the voluntary compliance approach

Stepping back and looking at all these trends together, it becomes clear that NCDOL’s hands-off approach to workplace protections are ineffective at preventing workplace deaths—penalties are too low, enforcement is too lax, and investigations are too few to deter bad actor employers from putting their workers’ lives at risk. If voluntary compliance were working as intended, we would expect to see North Carolina’s workplace fatality rate fall as overall enforcement does But we don’t. Instead, we see weakening enforcement accompanied by rising workplace deaths, fatality rates above the national average, and a rapid increase in FATCAT incidents. NCDOL’s approach is simply inadequate to protect the lives of workers on the job.

Yet the rise in workplace deaths has also coincided with a long-term drop in the rate of nonfatal workplace injury and illness, according to the BLS Survey of Occupational Illnesses and Injuries.25 Indeed, North Carolina’s nonfatal workplace injury rate in 2018 was at near historic lows—2.4 per 100 workers, virtually identical to the 2017 rate of 2.3.26

At first glance, this result is somewhat counterintuitive—one would expect workplace fatalities and workplace injuries to follow the same general trends. Yet as with FATCATs, the devil in the data details. Specifically, this particular BLS survey is a voluntary survey of employers. Many employers may not choose to participate at all, and those who do may not even offer accurate information about the injuries occurring on their worksites. As a result, under-reporting is rampant, and the survey cannot be trusted to provide an accurate representation of workplace injuries.

In fact, a 2009 Government Accounting Office (GAO) report documented that many workplace injuries are not recorded on employers’ recordkeeping logs required by OSHA and consequently are under-reported to the BLS resulting in a substantial undercount of occupational injuries in the United States.27 Other reasons for under-reporting include workers’ reticence to report injuries for fear of losing their jobs; employers’ incentive and disincentive programs that discourage workers from reporting injuries; and obstacles in both the OSHA recordkeeping regulation and Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) that affect the collection of complete data.28 Further, employers with under 10 workers don’t even have to keep OSHA injury records, making it easy to hide workplace injuries. However, it remains hard to hide workplace deaths, due to media coverage and required reporting to BLS and OSHA.

As a result, the reported drop in occupational injury rates does little to support the idea that NCDOL is doing enough to protect workers on the job. Instead, it is clear from our analysis—along with the basic annual fatality rate—that NCDOL is not doing enough to protect workers on the job. In turn, this reflects the basic shortcomings of the voluntary compliance model.

At its heart, voluntary compliance assumes that all employers operate in good faith most or all of the time, and all that’s needed to ensure they follow the rules is to educate and train them to do so and then reward them with recognition ceremonies when they do. This view is certainly optimistic. But it fails to grapple with North Carolina’s own history of devastating workplace disasters like the 1991 Hamlet fire, where chicken-processor Imperial Foods’ willful disregard for basic workplace safety in the pursuit of maximizing profit directly led to the deaths of 25 workers.29 Voluntary compliance may benefit the many employers, especially small business owners, who doubtless want to play by the rules and not cut corners, and NCDOL’s efforts to support these good employers through training and education may genuinely help them accomplish these goals.

Yet voluntary compliance fails in the face of bad-actor employers who feel the need to cut corners with workplace health and safety in the same way as Imperial Foods prior to the Hamlet fire. No amount of training and recognition societies will convince employers like this to adequately protect their workers—and they are clearly undeterred by NCDOL’s enforcement efforts. Indeed, Willful violators such as Associated Scaffolding, Powder Coating Services, and Family Attractions Amusement Company, all of whose unsafe conditions resulted in the needless deaths of workers, had their violations and penalties significantly reduced by NCDOL.

So it is not surprising that voluntary compliance has not reduced the workplace fatality rate. Bad actor employers are willing to put their workers’ lives at risk, and NCDOL’s hands-off enforcement is clearly unable to deter them.

8. Policy Recommendations

Workers’ lives have intrinsic value, and it’s clear NCDOL is not adequately protecting them in North Carolina. By both federal and state measures, the agency’s hands-off, voluntary compliance approach has failed to halt rising workplace deaths or increasing incidents of fatalities/catastrophes since 2012. Low penalties, lax enforcement, and absurdly infrequent inspections haven’t made workplaces safer—they’ve only made it more difficult for the state to protect workers on the job. Instead of continuing its dangerously laissez faire approach, NCDOL should strengthen direct enforcement in the following ways:

- Inspect every work-related fatality reported to NCDOL by employers, regardless of size and industry hazard level. Federal OSHA inspects work-related fatalities in all employers—regardless of size—under their jurisdiction, and there is no reason why NCDOL cannot do the same. Use state funds for inspecting small farms and employers on the low-hazard exemption list. There should be no blanket exemptions for any fatality, period.

- Enact higher penalties, especially in cases involving fatalities. NCDOL should raise its penalties to (at least) the national average and fully adopt the Obama-era maximum penalties for Willful and Serious violators. Penalties must be high enough to deter corporate bad behavior and better protect workers’ lives on the job.

- Enforce the Willful violation to the maximum extent under the law. NCDOL should hand out the Willful violation whenever and wherever it is merited; assess the full, Obama-era penalty; and fight efforts to reduce the violation and penalty during settlement negotiations and administrative review.

- Hire more inspectors and conduct more frequent inspections. For inspections to work as intended, there must be enough of them to ensure workplaces are regularly monitored for compliance. At the bare minimum, NCDOL needs to hire enough inspectors to conduct the national average number of inspections, especially in high-fatality sectors like construction and agriculture.

- Conduct inspections of every workplace reporting FATCATs. As part of this, NCDOL should also fully investigate every FATCAT case involving alleged independent contractors to make sure that the worker is not misclassified and is indeed an employee. This could involve opening a misclassification investigation and using it to identify potential health and safety violations, along with determining whether the worker was improperly classified. NCDOL should also provide a public explanation why no investigation was opened in every fatality case where this happens.

- Implement the same practices of federal OSHA of interviewing workers away from their workplace and employer to assure that workers do not feel intimidated to speak.

- Pursue a both/and approach to workplace protections that couples training and safety recognition with tougher standards, higher accountability, and aggressive enforcement. Carolina Star, the Million Hour Safety Awards, and other recognition programs provide an important way of celebrating successful employer improvement of workplace safety. Likewise, NCDOL’s training programs provide critical resources that help businesses with compliance. Although they are clearly no substitute for tough enforcement, they could play an important support role alongside an aggressive enforcement policy. NCDOL should deploy both the carrot and the stick to ensure better workplace safety.

Acknowledgements

This report could not have completed without Debbie Berkowits, Peg Seminario, MK Fletcher, Rebecca Reindel, and Carol Brooke and comments, feedback, and patient explanations about the health and safety enforcement process. Special thanks to NC Justice Center staff for their invaluable help with preparing this report for release, including Phyllis Nunn, Cristina Galvan, Kris Nordstrom, and Julia Hawes.

Footnotes

- US Occupational & Health Administration. Inspection information for inspection number 317838167

- US Occupational & Health Administration. Inspection information for inspection number 317721561.

- US Occupational & Health Administration. Inspection information for inspection number 317715852

- Although the NCDOL fatality count is in federal fiscal years and the BLS count is in calendar years, they overlap for nine months each year and are sufficiently comparable to identify the basic trend. Although we could have rebuilt the NCDOL fatality measure to provide calendar-year workplace death counts, we felt that it was important to use the same count that the agency itself uses and reports in order to minimize confusion.

- US Occupational & Health Administration Timeline. https://www.osha.gov/osha40/

timeline.html - AFL-CIO. (2019) Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect, 2019. A National and Stateby-

State Profile of Worker Health and Safety in the United States, 28the edition.

Washington, DC. - Specific details can be found at: https://www.labor.nc.gov/safety-and-health/

occupational-safety-and-health/occupational-safety-and-health-topic-pages/

special-emphasis-programs#what-seps-are-currently-in-effect-in-north-carolina? - NC Department of Labor. Special Emphasis Programs. https://www.labor.nc.gov/

safety-and-health/occupational-safety-and-health/occupational-safety-andhealth-

topic-pages/special-emphasis-programs#what-seps-are-currently-ineffect-

in-north-carolina? - North Carolina Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Division Bureau of Compliance Field Operations Manual. Chapter VI, Penalties. The online version of the document (Revision 15) has an effective date of January 16, 2015, before the new maximums went into effect in 2016. Accessed online at: https://files.nc.gov/ncdol/osh/osh-enforcement-procedures/fom06o.pdf. The penalties chapter

- US Occupational & Health Administration. Federal Employer Rights and

Responsibilities Following an OSHA Inspection, https://www.osha.gov/

Publications/fedrites.html - US Occupational & Health Administration, Penalties, https://www.osha.gov/

penalties - US Senate, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. (2008). When a

Worker is Killed: Do OSHA Penalties Enhance Workplace Safety? Hearing, April 29,

2008. https://www.help.senate.gov/hearings/when-a-worker-is-killed-do-oshapenalties-

enhance-workplace-safetyd - Martha T. McCluskey, Thomas O. McGarity, Sidney Shapiro, and CPR Policy Analyst

Katherine Tracy. (2016). “OSHA’s Discount on Danger: OSHA Should Revise Its

Informal Settlement Policies to Maximize the Deterrent Value of Citations.” Center

for Progressive Reform. http://www.progressivereform.org/OSHADiscountPaper.cfm - Ibid.

- Author’s analysis of the 170 fatality cases where penalty data was available from

Federal OSHA. - US Occupational & Health Administration, https://www.osha.gov/penalties

- Interview with Debbie Berkowtiz, National Employment Law Project.

- AFL-CIO. (2019) Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect, 2019. A National and Stateby-

State Profile of Worker Health and Safety in the United States, 28the edition.

Washington, DC. - OSHA INSTRUCTION, DIRECTIVE NUMBER: CPL 2-0.51J, SUBJECT: Enforcement Exemptions and Limitations under the Appropriations Act. Accessed online at https://www.osha.gov/enforcement/directives/cpl-02-00-051

- It is also possible that this data reflects coding decisions made by NCDOL staff in reporting incidents to US OSHA, and that these incidents are not receiving inspection for other reasons covered by another category (e.g., traffic accidents, deaths by natural causes, etc). Without more detailed, publicly available case-level data about these incidents, it is impossible to know for certain why the decision to not inspect was made. See remaining discussion of the other category for more.

- Author’s analysis of Fatal Work Injury Counts, by event, recent years. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/charts/census-of-fatal-occupational-injuries/fatal-work-injury-counts-by-event-recent-years.htm

- Catherine Ruckleshaus and Ceilidh Gao. (2017). FACT SHEET: Independent Contractor Misclassification Imposes Huge Costs on Workers and Federal and State

Treasuries. National Employment Law Project. https://www.nelp.org/publication/

independent-contractor-misclassification-imposes-huge-costs-on-workers-andfederal-

and-state-treasuries-update-2017/ - National Conference of State Legislators. (2019). Employee Misclassification. http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/employee-misclassificationresources.aspx

- Catherine Ruckleshaus and Ceilidh Gao. (2017). FACT SHEET: Independent Contractor Misclassification Imposes Huge Costs on Workers and Federal and State Treasuries. National Employment Law Project. https://www.nelp.org/publication/independent-contractor-misclassification-imposes-huge-costs-on-workers-andfederal-and-state-treasuries-update-2017/

- McDowell News. (2019). NC’s workplace injury and illness rate remains at a historic

low. https://www.mcdowellnews.com/news/nc-s-workplace-injury-and-illnessrate-

remains-at-a/article_651a7470-0ae6-11ea-a8f4-bb4825984148.html - Ibid.

- Kathleen M.Fagan and MichaelJ.Hodgson. (2016). Under-recording of work-related injuries and illnesses: An OSHA priority. Journal of Safety Research. https://www.

osha.gov/ooc/underrecording_fagan_hodgson.pdf - Azaroff, Levenstein, & Wegman, 2002; Boden & Ozonoff, 2008; Leigh et al., 2004; Rosenman et al., 2006; Spieler & Wagner, 2014) courtesy of Debbie Berkowtiz.

- Simon, Bryant. (2017). The Hamlet Fire: A Tragic Story of Cheap Food, Cheap Government, and Cheap Lives. https://www.amazon.com/Hamlet-Fire-Tragic-Story-Government/dp/1620972387

Justice Circle

Justice Circle