The start of the Great Recession, and the collapse of financial markets in the fall of 2008, is more than a decade behind us, yet its impact still reverberates through North Carolina communities and households. Policymakers should use the lessons learned from the Great Recession to prepare now to protect North Carolina’s people and communities from the next economic downturn.

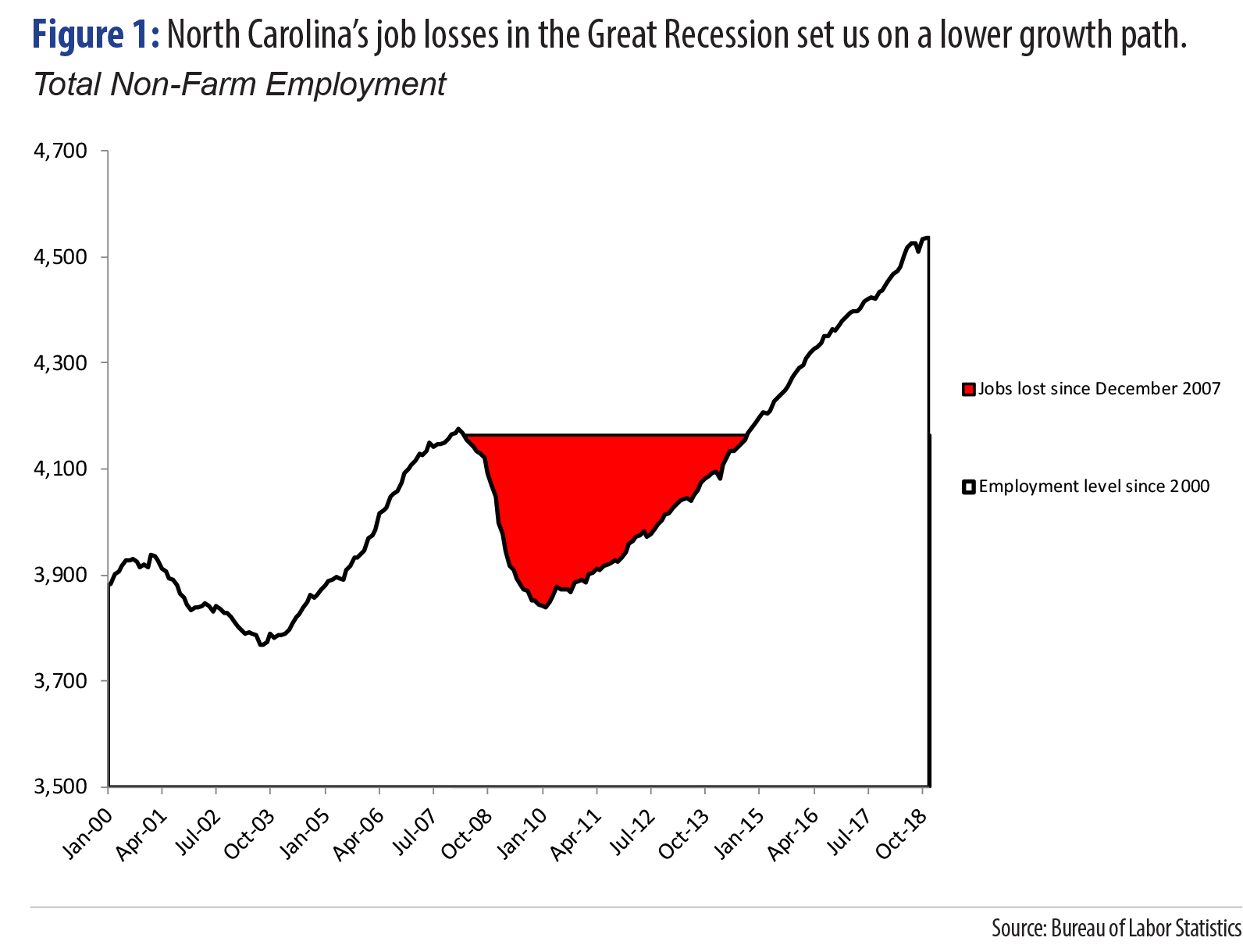

North Carolina experienced one of the sharpest drops in employment during the Great Recession of any state in the country. From December 2007 to the absolute lowest employment level in February 2010, North Carolina saw a decline of 325,000 jobs, or roughly 8 percent of total employment (See Figure 1).1 While North Carolina has since recovered to pre-Recession employment numbers of jobs, the state has never truly climbed out of the hold that the economic collapse left behind.

The recovery that officially began in July 2009 has been slow to produce the level of job growth necessary to keep labor force participation high, to generate broad-based wage gains, and to lift people out of poverty.2 The scars of the Great Recession are likely to be long-lasting and have clearly disrupted the well-being of many North Carolinians, with median household income still below pre-Recession levels, for example.3 To minimize the harms in the moment of a downturn and to reduce barriers to long-term growth prospects, public policy has a critical role to play.

It is unclear when the next economic downturn will begin, but the unprecedented length of the current expansion suggests that policymakers should prepare now for the ways in which economic shocks could disrupt the well-being of North Carolina families and the economy as a whole.

Lessons from the response to the Great Recession should inform state policymakers’ efforts. And specific systems —like the state’s unemployment insurance program, delivery of Food and Nutrition Services, budgeting practices and infrastructure investments — should be strengthened in North Carolina now. In so doing, policymakers can ensure that timely, effective policies can counterbalance the potential harmful effects of a downturn on every community’s ability to thrive.

Policy measures to fight the Great Recession worked well — before they were abandoned

Now that time has passed, there is a significant body of academic research documenting the specific and the broad policy responses to the Great Recession, primarily at the federal level (see Breakout Box on “Federal government must lead, but coordination with states is critical”).4

Using Moody’s macroeconomic model, economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi have summarized their findings regarding what could have happened in the U.S. economy without the policy responses of late 2008 and early 2009 as follows:

- “The peak-to-trough decline in real domestic product (GDP), which was barely over 4%, would have been close to a stunning 14%;

- the economy would have contracted for more than three years, more than twice as long as it did;

- more than 17 million jobs would have been lost, about twice the actual number.”5

Researchers have noted that among the most effective policy decisions in the aftermath of the downturn were expansion of emergency unemployment benefits, additional food assistance payments, and federal aid to states that helped to balance budgets without deeper spending cuts.6

While the response worked well in the depths of the recession, the pulling back on this response too early contributed to a slower recovery.7 The result was that state budgets across the country, including in North Carolina, still weren’t able to balance due to depressed revenues when federal aid to states went away and deep cuts were needed. In addition, households lost critical supports that helped them make ends meet, stay connected to the labor market, and minimize the loss of income and assets.8

Federal government must lead, but coordination with states is critical

The federal government has two key policy levers when responding to an economic downturn: monetary policy through the Federal Reserve and fiscal policy that can be enacted through legislation by Congress and signed by the President.

The federal government, unlike states, can incur debt to pay for priorities and has historically done so during downturns as a way to stabilize the economy. These short- and even medium-term debts can be addressed through stronger economic growth coming out of a recovery if the interventions and investments are effectively targeted and sustained until economic stabilization occurs.

The federal response can have the greatest benefit if it does not supplant state effort but adds to it. For example, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, federal aid to states for education and Medicaid was provided but required a commitment to maintain eligibility and the state’s existing commitment to the programs. For example, in the allocation of funds to primary and secondary education, the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, used existing state funding formulas as the primary distribution of funding across school districts and set in place requirements that state’s maintained their level of funding to public schools in FY2011 to at least the level in FY2009.9

When the federal government acts quickly and with the full power of the range of policy levers at their disposal, they can coordinate and connect to state systems, agencies, and policymaking to also support locally relevant interventions and effective implementation on the ground.

Future responses should be automatic and durable to achieve greatest benefits for North Carolinians.

A thorough review of the policy response has many lessons for policymakers at the federal and state level, including the early missed opportunities that failed to prevent economic shocks at the outset.10 Two broad lessons from the Great Recession that matter for state policymaking should be emphasized—the need for both quick response and commitment to maintain public investments and policy interventions until the economy is in full growth mode.

First, policymaking can take time that is precious in the context of an economic downturn, so establishing rules that create quick and, as possible, automatic stabilization is critical. For example, at the federal level, rather than require Congressional action to extend Emergency Unemployment Compensation programs, policy analysts have proposed setting up triggers for such programs based on indicators of economic hardship. Similarly, requiring states to pursue waivers on time limits in food assistance could be replaced with provisions that automatically waive time limits in states that reach certain unemployment rates.

Second, the failure to sustain investments to secure a more robust recovery after the Great Recession, as well as the lack of a more significant commitment to infrastructure investment, should provide today’s policymakers with lessons on the length and scope of public commitment needed. In North Carolina, the temporary tax package was repealed before employment and revenues had fully recovered to pre-Recession levels, ensuring that policymakers would cut programs like education and health care. Nationally, the reduction in additional food assistance support came before employment and household incomes had recovered.

North Carolina must establish more effective stabilizing policies ahead of the next downturn.

North Carolina policymakers can establish a stronger foundation for our economy to withstand the next economic downturn based on the lessons of the past Recession. Below are a few key state-level policy options that should be enabled and strengthened to ensure North Carolina communities have a solid foundation from which to respond to the next downturn.

- Unemployment insurance: Of particular importance is addressing the diminished effectiveness of the state’s unemployment insurance system by primarily returning the program to the national standard of 26 weeks and calculating benefits based on the average of the highest quarters of earnings and not capping benefits for higher wage earners. North Carolina’s current unemployment insurance system provides too little to too few jobless workers for too short a time period. By also adopting work-sharing and pursuing a return to attached claims, workers—and the employers—who will eventually want them back when the economy rebounds will be better off.

- Assistance to meet basic needs: In times of economic downturns, households face increased pressure from rising costs and lower or lost income. There are many policy options to help North Carolinians be able to pay for their basic needs:

- North Carolina has successful foreclosure prevention programs that are in place and can be quickly ramped up with additional funding support as needed as well as Housing Tax Credit and a Housing Trust Fund that when funded can keep businesses operating, workers working and build more affordable housing units in communities across the state.

- Expansion of Medicaid would go a long way to ensuring that the stabilizing benefit of health care coverage and affordable health care are in effect for the next downturn. In addition, given the potential for federal policymakers to consider picking up state payments again, the potential benefit to North Carolina would be even great.

- Removing barriers to pursue flexibility in the food assistance program would allow North Carolinians living in particularly hard-hit labor markets to access the support they need to put food on the table even if jobs have not returned. The prohibition enacted by the General Assembly in 2015 for all future pursuit of a waiver will create greater barriers to stabilizing local economies and keeping people from falling into greater hardship.

- Fiscal policy: There are a number of ways in which North Carolina is on more precarious footing than before the Great Recession:

- The tax code already is falling short of needs in communities, and thus communities are already struggling in the current expansion. The diminished baseline of investment sets an even lower starting point for when recessions reduce revenues and will result in deeper cuts to programs and services that include eligibility restrictions. Starting now to rebuild the capacity to raise revenue and doing so equitably is critical.

- One area where the state is positioned better is that the Rainy Day Fund holds more than $1 billion. The challenge will be accessing those dollars. Removing the two-thirds vote required to access these funds in an emergency will allow for quicker response from state leaders to ensure that what will inevitably be far deeper cuts to services and eligibility for programs are minimized.

- Infrastructure projects: For various reasons, including in preparation for the low-borrowing costs that could be made available in a downturn, North Carolina should have a list of shovel-ready infrastructure projects that could be quickly funded to provide jobs to local workers and businesses. Restrictions on who and how local and state governments determine who they work with should be removed to ensure that governments can pursue the greatest flexibility and the maximum benefit for workers, businesses, and the broader economy.

Together, these policy changes would go a long way to ensuring North Carolina can respond to the needs that will arise with the next downturn. And, in the meantime, communities across the state will benefit from achieving a higher level of well-being with the support of these critical economic programs.

Footnotes

- Analysis of U.S. Department of Labor, Local Area Unemployment Survey and Current Employment Survey from the Economic Policy Institute, Job Watch.

- State of Working America and State of Working NC. accessed at: http://stateofworkingamerica.org/

- Irons, John, September 2009. Economic Scarring: The Long-Term Impacts of the Great Recession. Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC.

- https://www.brookings.edu/research/nine-facts-about-the-great-recession-and-tools-for-fighting-the-next-downturn/ and Bernstein, Jared and Ben Spielberg, March 21, 2016. Preparing for the Next Recession: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Center on Budget & Policy Priorities: Policy Futures Series.

- Blinder, Alan S. and Mark Zandi, October 15, 2015. The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One. Center on Budget & Policy Priorities: Policy Futures Series.

- Blinder and Zandi, October 2015; Bernstein and Spielberg, March 2016

- https://www.epi.org/publication/why-is-recovery-taking-so-long-and-who-is-to-blame/

- https://www.epi.org/publication/why-is-recovery-taking-so-long-and-who-is-to-blame/

- https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/federal-education-budget-project/ed-money-watch/intricacies-of-the-state-fiscal-stabilization-fund-for-education/

- Bernstein and Spielberg, March 2016.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle