Making certain that every infant is safe and developing, every toddler is thriving, and every preschooler is prepared for kindergarten smooths the pathway to lifetime success and happiness for all North Carolinians. Recent data collected by the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation finds that North Carolinians recognize the importance of the early years and want to see policymakers make a significant investment to ensure more children can access quality early childhood education.

Yet the ability to both serve more children and ensure the quality of learning environments is currently constrained by the lack of public funding. Absent that public investment, the growing cost of child care for many families threatens to overtake housing as the major household expenditure. It can also force families to make difficult choices about remaining in the labor force and meeting all of the needs of their growing children.

North Carolina’s early childhood system is confronting the reality that the growth of low-wage work presents two major barriers to the ability to achieve higher quality and serve more children: (1) Parents simply cannot afford to pay rising child care costs with stagnate and low wages, and (2) Early childhood educators can’t make ends meet on their low wages and deliver a quality learning environment for each child.

North Carolina ranks 42nd for its high share of working people with children who earn poverty wages (12.1 percent). The rising cost of high-quality child care makes it difficult for many North Carolinians — from those earning poverty wages to those earning median wages in the state — to afford a quality early learning experience for their children, which is critical to those children’s lifetime earnings. At the same time, the emerging research is clear that the quality of pay and work environments has a significant relationship to the delivery of professional and quality services. For many early childhood educators, their pay is simply too low to make ends meet and provide quality child care for their own children, and this holds back the ability of the state to deliver a high-quality learning environment to every child.

This BTC Report provides an overview of the compensation received by early childhood educators, provides evidence for the positive contribution higher wage rates could make to the state’s goal of quality early childhood experiences for each child, outlines potential sources of funding to support the goal of taking a two-generation approach to our state’s early childhood system, and shares policies that have proven effective within the early childhood system to support early childhood educators.

Early childhood workers can’t afford quality care for their children

While North Carolina has led the nation in high-quality early childhood programs, it has fallen short in ensuring that early childhood educators can meet the needs of their own families, which leads to challenges in recruiting and retaining people in the profession. In North Carolina, as well as in many other states, early childhood educators are in economic distress because their salaries remain low, while their work is highly skilled. National research finds that this reality falls disproportionately on early childhood educators who are women — who comprise the vast majority of the early childhood workforce (95.6 percent) — educators of color, and those working with the youngest children. In North Carolina, a 2015 workforce study by the Child Care Services Association found that infant and toddler teachers had a median wage of $10 per hour, compared to a median wage for pre-school teachers of $11.39 per hour.

Early childhood educators are responsible for safeguarding and facilitating the development and learning of our nation’s youngest children; they make it possible for parents to pursue employment outside of the home and spend more time at work, which has increasingly become an economic necessity. However, their wages do not match the importance and long-term impacts of their work.

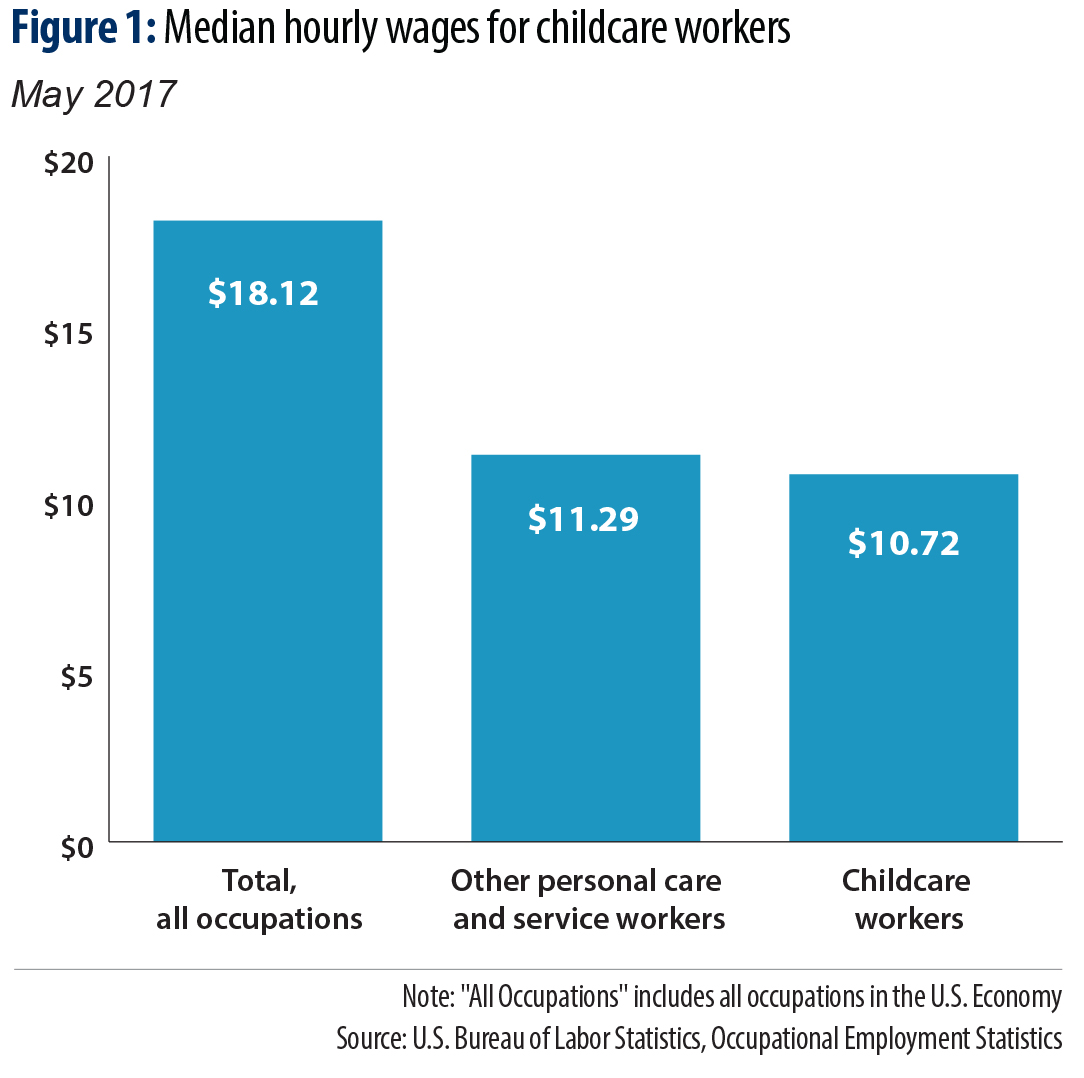

In 2017, analysis of state level data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) finds that in North Carolina, the median wage for educators that BLS classifies as “child care workers”— those teaching children younger than 4 years old—was $9.86; this was a 1 percent increase since 2015, but falls behind the 2017 national median hourly wage for child care workers ($10.72).

Further, according to a recent report from the Working Poor Families Project, on average, “early childhood educators are paid only slightly more than cashiers and dishwashers, and slightly less than coat and locker room attendants, and less than half of what kindergarten teachers earn despite working full-time year-round.” Additionally, almost half of the workers that the Bureau of Labor Statistics classifies as “child care workers” enroll in some form of public assistance for themselves or their families, such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and many are eligible for child care subsidies themselves.

In addition to salaries that fall short of national wages, North Carolina early childhood educators face important wage scale and wage progression differences based on their ability to gain employment at a high quality program. A 2015 report from the Child Care Services Association identifies compensation differences for teaching staff that depend on whether or not they work in a program that has an NC Pre-K classroom on site. The report notes that licensed early care and education programs with NC pre-K classrooms have substantially better compensation at all levels than those without such classrooms.

Child care costs are especially heavy for early childhood educators who earn considerably less than workers in other occupations. In 32 states and D.C., the cost of center-based infant care is greater than one-third of the income of a typical pre-school teacher; in 21 states and D.C., infant and toddler educators would have to dedicate more than half of their annual income to pay for center-based infant care. The result of high child care costs is that many early childhood educators must receive a subsidy to ensure their own child’s early education. Publicly available child care subsidies are limited; however, if their employers offer reduced admission for their children, this affects the overall availability of resources for the child care center.

Many early childhood educators are forced to forego high quality child care for their own children, and must rely on informal child care or family care to meet their child care needs. Others may move to other professions in order to earn wages that allow them to meet their families’ needs. In North Carolina, 1 out of 5 teachers leave their workplaces in a year — which survey data shows is directly tied to wages — creating disruptions to the learning environment for children at a critical time in their development.

Investing in infant and toddler educators with lowest wages

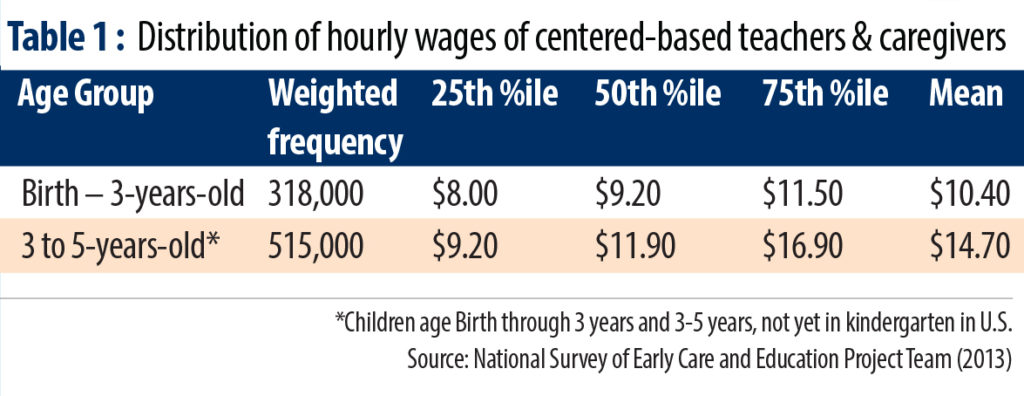

National research shows that on average, 25 percent of center-based teachers and caregivers serving infants and toddlers earn only slightly more per hour than the current federal minimum wage of $7.25, which is considered to be inadequate to support a single adult without children.

The impact of low compensation for early childhood educators is especially pronounced for infant and toddler educators who make less than their pre-school counterparts — NC infant/toddler staff receive $10 per hour and NC pre-school teaching staff receive $11.39 per hour. As shown in Table 1, at the national level, center-based infant and toddler educators — those who work with children 3 years old or younger — earn about 70 percent of what those working with children 3 to 5 years old earn.

In recognition that infant and toddler educators in North Carolina experience the lowest wages in early education, the state has taken some important steps toward investing in its youngest children by also investing in the adults who care for them. The Infant Toddler Educator AWARD$ program, which is made possible through the partnership between the Child Care Services Association and the NC Division of Child Development and Early Education, is designed to better compensate and retain well-educated teachers working with North Carolina’s youngest children.

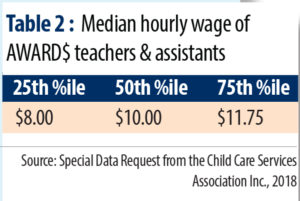

Through this program, infant and toddler teachers are given incentives to stay in the field and grow their own skills and knowledge. Across the state, salary supplements are awarded to over 900 eligible full-time infant and toddler educators with at least an associate’s degree in Early Childhood Education or its equivalent. This represents an estimated 34 percent of eligible infant and toddler educators in the state. While the Infant Toddler Educator AWARD$ program is funded by the Division of Child Development and Early Education, the Child Care Services Association administers the education-based salary supplements based on the Child Care WAGE$ program to help address the compensation gap between infant-toddler teachers and pre-school teachers. Although the Infant Toddler Educator AWARD$ program is in its early stages, it will serve as an important mechanism for delivering much needed boosts to the quality of care for the state’s youngest children through its increased wages for early childhood educators (see Table 2).

Through this program, infant and toddler teachers are given incentives to stay in the field and grow their own skills and knowledge. Across the state, salary supplements are awarded to over 900 eligible full-time infant and toddler educators with at least an associate’s degree in Early Childhood Education or its equivalent. This represents an estimated 34 percent of eligible infant and toddler educators in the state. While the Infant Toddler Educator AWARD$ program is funded by the Division of Child Development and Early Education, the Child Care Services Association administers the education-based salary supplements based on the Child Care WAGE$ program to help address the compensation gap between infant-toddler teachers and pre-school teachers. Although the Infant Toddler Educator AWARD$ program is in its early stages, it will serve as an important mechanism for delivering much needed boosts to the quality of care for the state’s youngest children through its increased wages for early childhood educators (see Table 2).

Problems of low-wage work for early childhood educators

Poor compensation comes at a price for early childhood educators’ well-being and, in turn, for their families and the children entrusted to their care. High levels of economic insecurity for early childhood educators and the stress it fuels can undermine their capacity to remain focused, to be present, and to engage in the intentional interactions that facilitate young children’s learning and development.

A recent national study examined the relationship between economic worry and program quality through a survey of 338 center-based teaching staff employed in predominantly publicly funded programs. Three-quarters of teaching staff expressed worry about having enough money to pay monthly bills, and 70 percent worried about paying their housing costs or routine health care costs for themselves or their families.

Staff who expressed significantly less economic worry and overall higher levels of adult well-being worked in programs rated higher on the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) Instructional Support domain. When CLASS Instructional Support ratings are higher, teaching staff were more likely to promote children’s higher-order thinking skills, provide feedback, and use advanced language, which stimulates conversation and expands understanding and learning.

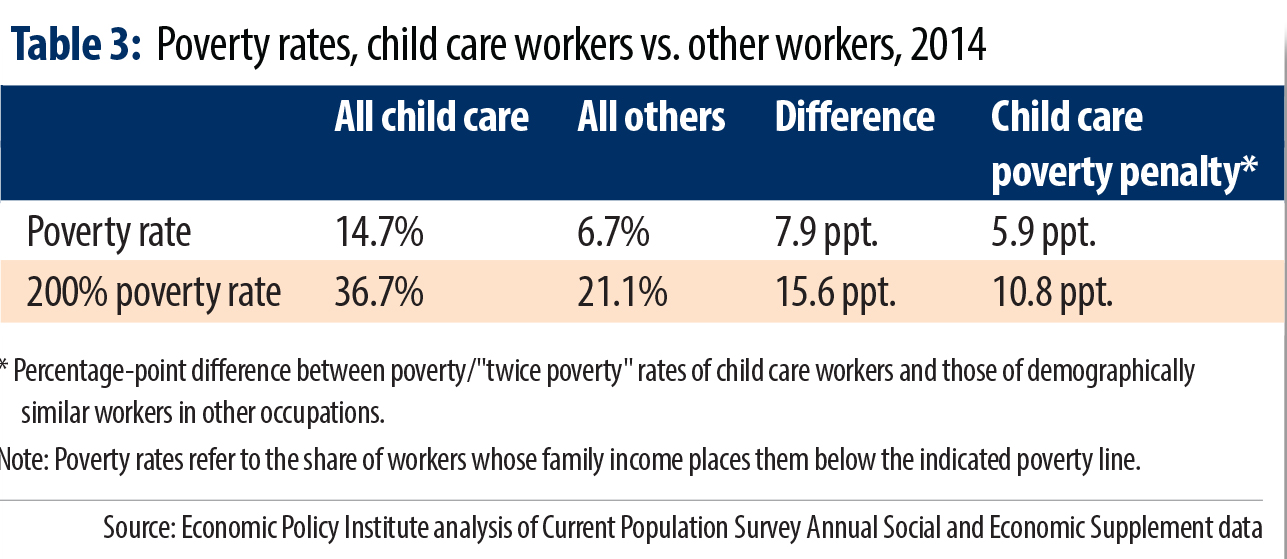

Additionally, early childhood educators have a harder time making ends meet with their salaries compared to workers in other occupations. As such, a substantial amount of early childhood educators and teaching staff live in poverty and must rely on resources other than wages. In 2014, almost half (46 percent) of early childhood educators and their families relied on one or more public support programs each year, in contrast to 25 percent of the overall workforce. In 2015, 56 percent of North Carolina early childhood teaching staff’s total household income was below $30,000. In the previous year, over one-third (36.7 percent) of early childhood educators lived in families with income that fell below two times the poverty line, compared with 21.1 percent of workers in other occupations.

Additionally, early childhood educators have a harder time making ends meet with their salaries compared to workers in other occupations. As such, a substantial amount of early childhood educators and teaching staff live in poverty and must rely on resources other than wages. In 2014, almost half (46 percent) of early childhood educators and their families relied on one or more public support programs each year, in contrast to 25 percent of the overall workforce. In 2015, 56 percent of North Carolina early childhood teaching staff’s total household income was below $30,000. In the previous year, over one-third (36.7 percent) of early childhood educators lived in families with income that fell below two times the poverty line, compared with 21.1 percent of workers in other occupations.

How other states invest in the early childhood workforce

Investments in the early childhood workforce help to ensure a high-quality and comprehensive working and learning environment for teachers and children. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, a variety of promising early childhood workforce investment strategies have been used across the United States.

Several states are investing in the early childhood workforce by increasing the wages of early childhood educators. Between 2015 and 2017, early childhood educators experienced nearly a 7 percent increase in wages after being adjusted for inflation, and 33 states saw increases in early childhood educator wages after adjusting for inflation. While these wage increases translated to approximately $0.67 per hour due to the low wage nature of the early childhood workforce, in some cases, the increase was substantial: the District of Columbia and Rhode Island had increases of more than 20 percent, and a further four states had increases between 10 and 15 percent (Arizona, Hawaii, North Dakota, and Vermont).

Other states have attempted to simultaneously increase teacher qualifications and teacher salaries. High-quality public preschool programs in Boston, Michigan, New Jersey, and Tulsa have made significant strides toward increasing teacher compensation in concert with qualifications as they require lead teachers to have a bachelor’s degree with a specialization in early childhood.

A number of states have leveraged federal legislation, using funds from the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), to invest in the early childhood workforce. In October of 2017, Louisiana’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education incorporated ESSA plans that include but are not limited to: a five-year plan for transitioning to a teacher preparation accountability system, developing resources that support early learning environments and aid in transitions throughout the pre-K-college continuum, and adopting early childhood education competencies.

Oregon aligned its ESSA plan with the 2016 Educator Advancement Report, which promotes a system across the pre-K and early elementary grades. Oregon seeks to link early learning providers with the K-3 public school systems, and it wants to invest in developmentally appropriate, culturally responsive, and aligned professional learning across pre-K-12. The state will invest in induction and mentoring programs, and it will increase scholarships to recruit linguistically and culturally diverse educators. Oregon also will offer in-service training to strengthen early childhood standards alignment and early literacy.

Some states have adopted or expanded programs such as tax credits, minimum wage legislation, and paid leave programs, in order to alleviate the effects of low earnings and poor job quality. Designed to benefit workers and their families across occupations, rather than the members of one field in particular, these support policies play a key role in shaping job quality and working conditions in the United States.

N.C. early childhood workforce programs need funding to fully realize their benefits

North Carolina has not only led the nation in designing an early childhood system, it has consistently built the economic well-being of its workforce into considerations of quality and effectiveness. North Carolina set up model programs to help educators receive scholarships for higher education with the hope that the wages of early childhood educators would be in line with the overall teaching profession and what it takes to make ends meet, as well as support the goal of creating quality learning environments for each young child in our state.

These programs provide a structure to recognize credentials and what early childhood educators need while acknowledging that private providers may not be able to fully compensate workers for the value of their services to society. The commitment to boost wages and compensation tied to credential and educational attainment is a critical component to these programs and one that should be expanded to reap greater benefits for the state and early childhood program quality.

Many early childhood programs in the state report that it is difficult to attract people to the career of early childhood educators, noting that enrollment in programs at the state’s community college are low. One tool that has effectively been used to engage people in specific industries are clearly articulated career pathways. Career pathways

“offer career advancement through a progression of educational qualifications, training, and credentials that build on each other and are aligned with the needs of the industry. Additionally, the career pathways approach includes multiple entry and exit points to allow workforce members greater flexibility in acquiring skills and knowledge.“

Recent reports from the National Institute of Medicine and guidance issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have noted the importance of a career pathways approach for early childhood educators. Specifically, by articulating and recognizing the progression of workers through advanced skills levels and valuing that progression through increased compensation, early childhood educators are more likely to remain in the field and continue the process of skill acquisition. There are currently no certified career pathways by the NC Department of Commerce in early childhood in North Carolina, although the Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) Early Childhood® Scholarship Program is nationally recognized as an effective career pathway approach that recognizes the pathways to higher skills and supplements wages for attainment of credentials.

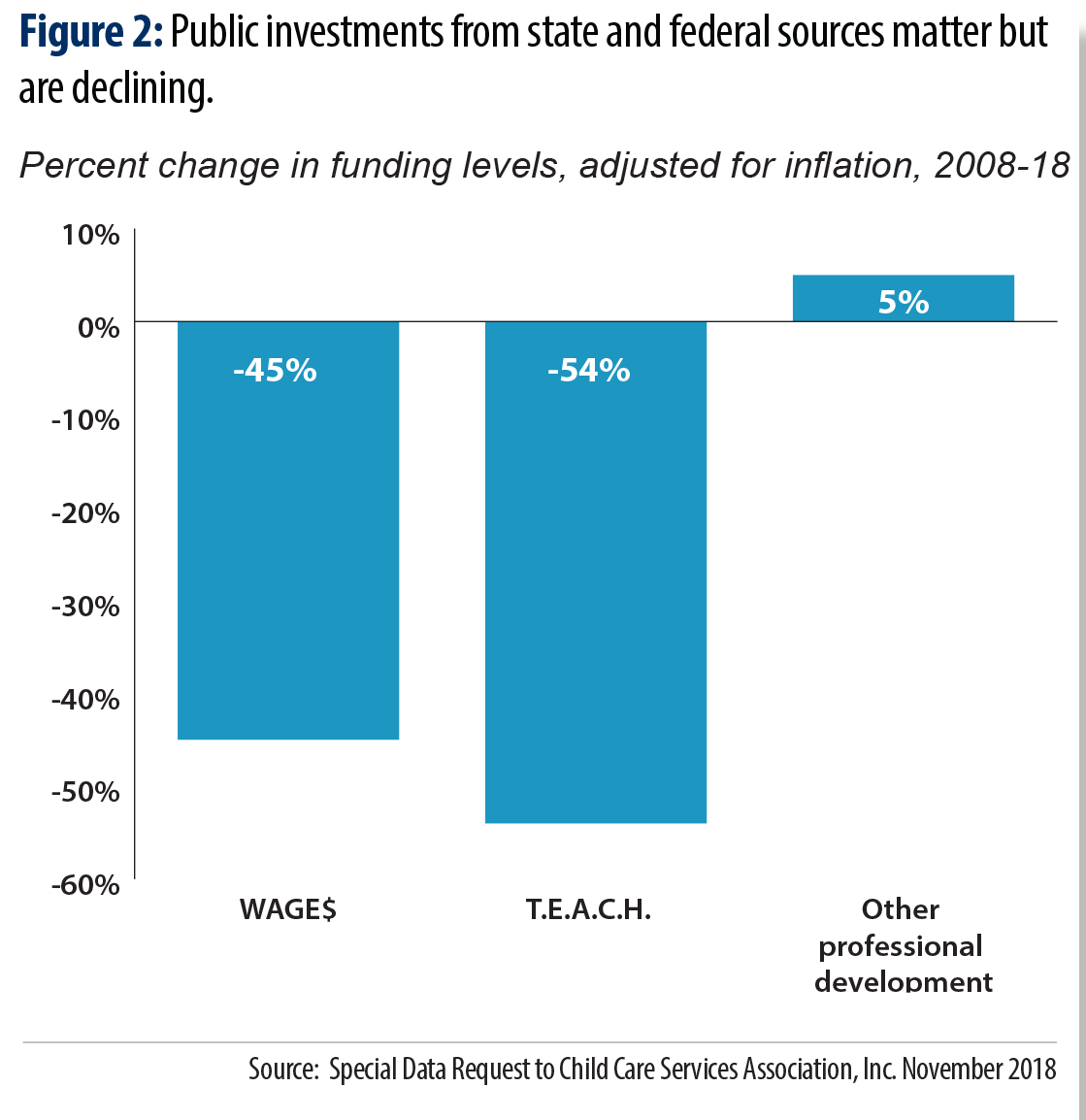

Currently in North Carolina, the state invests just $10.7 million on boosting the compensation of early childhood educators through a combination of state appropriations and federal dollars. North Carolina’s investment in these programs has declined since 2008 by more than half, while general professional development supports have increased by a mere 5 percent (see Figure 2).

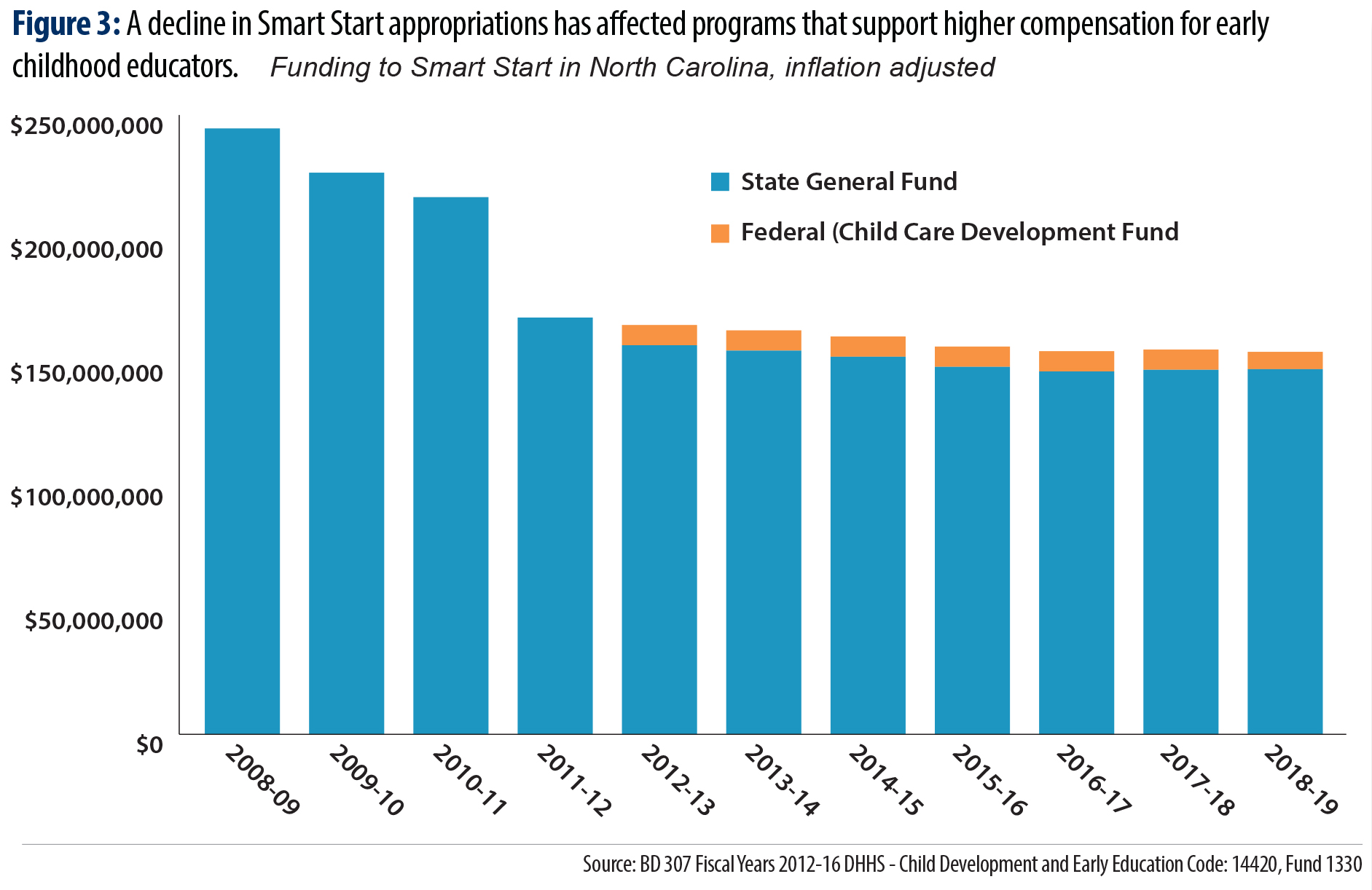

Funding for many of the programs that support higher compensation for early childhood educators is directly tied to the overall state funding delivered to the state’s Smart Start agencies, the network of county level anchors to the early childhood education system in the state. These institutions and the coordination role that they play with early childhood educators and service providers in their counties or regions provide support to the professional development and quality of programming. Funds for Smart Start were reduced by 37 percent since 2008 when adjusted for inflation, leading to disruptions in the delivery of a number of important quality programs for early childhood education, including wage and professional development. Along with the decline in Smart Start funding, many Smart Start agencies declined to continue participation in the WAGE$ program, which has yet to reach scale statewide due to both direct and indirect funding constraints.

N.C.’s programs to address compensation issues in early childhood workforce

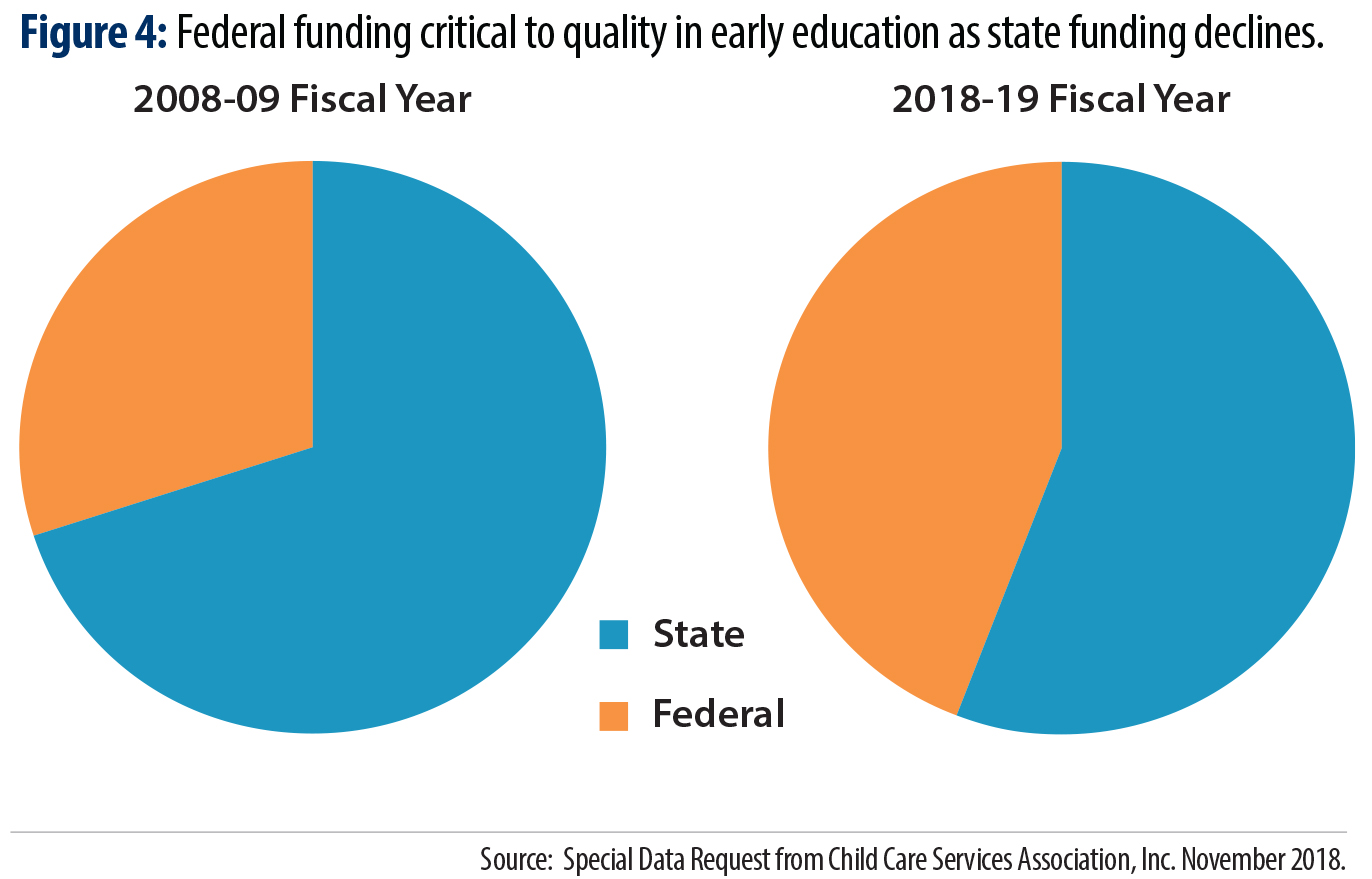

Since 2008, federal funds have not grown with demand and, combined with the shifts in allocations across various early childhood priorities, funding specific to wages and professional development of the workforce has fallen behind in the past decade. That said, in the past year, an increase in the amount of Child Care and Development Funds has meant the decline on the federal side is less pronounced than the state level decline. Indeed, if the state decline in funding matched the federal decline, North Carolina’s early education workforce would have an additional $8 million in funding for compensation.

The overall result of these shifts in levels and allocation of funding streams is that the state now relies more on federal dollars to support this state priority (See Figure 4).

Public investments can help compensate early childhood educators in a manner that approaches parity with salaries in public schools. Such investments will then help ensure that children benefit from more consistent, qualified educators during the early years when brain development, the establishment of trust, and the promotion of learning are most critical.

The Child Care WAGE$® Program

The Child Care WAGE$® Program is a statewide education-based salary supplement initiative that seeks to improve the quality of early care and education for young children by addressing the three primary factors associated with teacher quality according to research: education, stability, and compensation. The Child Care WAGE$® Program provides education-based salary supplements to low paid teachers, directors and family child care providers working with children from birth to age 5. Through these supplements and incentives, WAGE$ seeks to reduce staff turnover and make the early childhood profession more affordable and attractive to providers.

The Child Care WAGE$® Program is a funding collaboration between a county’s local Smart Start partnership and the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE). The full amount a partnership provides goes toward the wage supplements. To participate, local partnerships must fund the supplements with Smart Start dollars; Child Care Services Association (CCSA) administers the project in these counties with funds provided by DCDEE.

Teacher Education and Compensation Helps Scholarship Program (T.E.A.C.H.)

Created in 1990 by the Child Care Services Association, the Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) Early Childhood® Scholarship program aims to address the issues of under-education, poor compensation and high turnover within the early childhood workforce. The T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® Scholarship program is aimed at supporting teachers in getting a higher education through scholarship opportunities for early educators, including NC pre-K and infant toddler educators working in licensed facilities.

Additionally, unique scholarship programs are available for specialists within the early care and education system. The T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® Scholarship program offers a variety of scholarship options to study Early Childhood Education at all 58 community colleges and 16 bachelor degree granting colleges and universities across North Carolina. Typically, comprehensive core scholarships provide partial support for the following: in-state tuition, books, travel, and, if applicable, release time.

National research shows that on average, 25 percent of center-based teachers and caregivers serving infants and toddlers earn only slightly more per hour than the current federal minimum wage of $7.25, which is considered to be inadequate to support a single adult without children.

Investments in professional development for the early childhood workforce

Professional development opportunities funded through the Child Care Services Resource and Referral (CCR&R) network are important in keeping educators up-to-date on the latest practice and keeping workers engaged in continuous learning that could help lead to increased wages. The types of professional development opportunities most often supported through CCR&R include a variety of opportunities that support high-quality services, including workshops and certifications as well as enrollment in early childhood courses at local community colleges or universities. Such professional development opportunities are part of a comprehensive career pathway but must be combined with public commitments to wage increases since these opportunities are not guaranteed to result in a certification or credential. Further, there is as yet not a certified career pathway in North Carolina for early education that would allow for the transferability of skills training and certificates to ensure industry recognition across the state and employers.

North Carolina has the potential to increase its effort when it comes to delivering a high-quality early learning environment for each young child in our state by including efforts to improve the compensation of the early childhood workforce in its work to build an early childhood system that generates results. Given the evidence of what works in other states and what is needed particularly in North Carolina, there are systemic changes that can be made within the early childhood system itself as well as in the broader policies that address fiscal and economic conditions in the state.

Workforce compensation is key in building a quality early childhood system

First, despite the leadership of North Carolina in recognizing the importance of the compensation of early childhood workforce for program quality through establishment early on of T.E.A.C.H. and WAGE$, it is critical that the state take the additional step of building workforce compensation into the Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS). Eighteen states have standards for workforce compensation built into their QRIS, and eight extend those standards to home-based centers as well as community-based centers.

Second, the state should pursue the use of cost-based studies rather than market-rate studies to set reimbursement rates and fully fund the cost of delivering high quality early childhood programming in communities. While this would only impact programs participating in the child care subsidy program, it would set an important standard for all early childhood programs in the state. This is newly allowed under the recent reauthorization of Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) federal funds and presents a critical opportunity for the state to address the compensation and reimbursement issues across the state.

Third, state funding to create a state-level salary supplement program for all early childhood educators with degrees is needed to align compensation of early childhood educators with the K-12 pay structure. Such a program could build upon the lessons of WAGE$ and T.E.A.C.H., along with connecting with the Smart Start infrastructure to engage local providers and educators in implementation of such a program at scale.

Finally, the federal government has provided additional funding each year through the expansion of the Child Care and Development Block Grant. In North Carolina, these dollars were used to replace state commitments to the number of children served in the early childhood system, missing an opportunity to serve more children and improve the compensation of the workforce. While the early childhood system will always require multiple funding streams, particular attention to how to braid, blend, and build on each stream to ensure the reach and quality of programs should be the standard for funding decisions.

Supportive policies outside of the early childhood system that help achieve quality.

Beyond the early childhood system, there are a range of policy choices that can create a better outcome for early childhood educators and the quality of the early childhood system. The ongoing cuts to income tax rates for big companies and individual taxpayers has reduced the dollars available in the state and made it impossible for policymakers to meet the increased need for early childhood programs and improve the quality. These dollars — $900 million alone from the tax cuts that were phased in on January 1, 2019 — would go a long way toward expanding the support for professional compensation of the early childhood workforce and recognition of credential attainment.

Second, recognition for providers who are emphasizing workforce compensation and skills training that are currently underway could be scaled up beyond the communities where they are currently operating. Watauga County has launched a certification program that includes compensation for local child care providers who meet key benchmarks of quality, while several child care providers in Buncombe County participate in the community’s voluntary Living Wage Certification program and receive a supplemental boost through a small grant from the local Partnership for their commitment to quality. These programs have the potential to drive consumers to high quality providers and blend private dollars with public commitments.

Third, the state’s workforce development system and NC Works Commission should consider certification and funding support to early childhood education career pathways to further professionalize the field and solidify the training opportunities that will result in recognition through higher compensation.

Finally, recognition is needed that the state minimum wage, which mirrors the federal minimum wage but is lower than that of 29 states and Washington, D.C., is no longer reflective of what it costs to make ends meet. Proposals to raise the minimum wage over time should be considered by state policymakers to help boost the pay of all workers — especially workers in the early childhood field.

North Carolina has a robust infrastructure in place to support the early childhood workforce and strengthen the quality of early childhood programs. A focus on adequately and equitably funding that infrastructure will ensure that each child is able to thrive and that the workers — often parents themselves — can also thrive as well.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle