People trying to access high quality, affordable health insurance should not be met with work reporting barriers

A bill in the North Carolina legislature that would expand Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—and provide health coverage to 500,000 North Carolinians—contains a provision that would likely result in 23 percent fewer people gaining coverage. Specifically, House Bill 655 would take Medicaid coverage away from adults aged 18 to 49 unless they report at least 80 hours of work or volunteer activities in a month (See Breakout Box).

Providing an affordable, quality health insurance product through Medicaid will deliver significant health benefits in the form of access to preventive care, treatment and prevention of chronic disease, and, importantly, a sense of improved health.1 Increasing the currently lackluster performance in the state in health insurance coverage would also strengthen the economy. Research is clear that having health insurance—and Medicaid, in particular—results in higher labor force participation, employment levels, and earnings over time.2 It also reduces the financial burden of medical debt, allowing families to meet a host of important household needs that support healthier outcomes and intergenerational mobility.3

The provision in HB 655 to take Medicaid away from people who don’t meet a burdensome work requirement runs counter to the purpose of Medicaid, as courts have decided,4 and would minimize the benefits of closing the coverage gap in our state.

This BTC Report provides an overview of the available research on work reporting requirements as implemented in other states and programs, estimates the impact of work reporting requirements in North Carolina, and provides evidence that there is no fix to work reporting requirements.

North Carolina policymakers should move forward to immediately close the coverage gap, without erecting costly barriers to coverage and care.

A work requirement in North Carolina would likely cause 23 percent of expansion beneficiaries to lose their coverage

The process of job creation and connecting people to work cannot be achieved through the establishment of a requirement to report on work activities. The theory of proponents of work requirements is that, by requiring this reporting, people will find a job. Such a theory lacks evidence from real-world application. In fact, research shows that the strongest improvements to labor force participation and employment outcomes have come from income supports and the establishment of strong systems of referral and direct connection to work.5

More concretely, North Carolina’s labor market still is falling short of the job creation target necessary to provide the number of jobs that would meet the demand for work from the state’s working age population. Job creation that has occurred is highly concentrated in the state’s major metropolitan areas, leaving 49 counties with fewer jobs today than before the Great Recession 11 years ago. What’s worse is that 23 of those 49 continue to see fewer and fewer jobs each year.6 The jobs that are being created are so low-wage they to fail to ensure a family to make ends meet. In 2015, more than one-third of people of color who worked full time were still considered low-income.7

Breakout Box: Specific reporting requirements in House Bill 655

The proposed work reporting requirements in North Carolina are based on the flawed work requirements in the Food and Nutrition Services (SNAP) able-bodied adult without dependent (ABAWD)rule.8 It is also similar to the Medicaid work requirement Arkansas implemented in 2018, which caused more than 18,000 people to lose their coverage before a federal judge ordered the state to suspend the program. Under HB 655, adults without dependents and without a federally recognized disability would have to report 80 hours each month of work or education and skills training activities. It appears that failure to meet or report for three months would result in the loss of coverage for as long as 3 years.9

HB 655 includes specific exemptions from the reporting requirement:

a. Individuals caring for a dependent minor child, an adult disabled child, or a disabled parent.

b. Individuals who are in active treatment for a substance abuse disorder.

c. Individuals determined to be medically frail or with an acute medical condition that would prevent the individual from complying with the employment requirements.

d. Pregnant and post-partum women.

e. Indian Health Services beneficiaries.

f. Any other category of individuals required to be exempt by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The known impact of work requirements is that people lose, in this case, health insurance coverage. Using the experiences of other states, particularly Arkansas, it is possible to estimate the impact of work reporting requirements on the effort to close the coverage gap in North Carolina.

After a year of phasing in similar work requirements, over 18,000 Arkansans in need of health care lost their coverage due to sanctions. Studies found that many enrollees were either unaware or misunderstood the new requirements and a majority of those who were aware reported issues with the online system and could not get assistance in navigating the online portal.10 Some, especially in rural communities, lacked access to computers or reliable internet access in order to report hours worked. Others who are experiencing homelessness or dealing with a physical or mental disability are often unaware of changes to program requirements and typically have a more difficult time navigating the paperwork.11

Even for enrollees who managed to navigate the reporting system, the requirements did not lead to a meaningful increase in work participation.12 Many of the enrollees who met the requirements were already working but are employed in fields that are unstable and have unpredictable hours. Rather than increasing the number of people working, enrollees reported an increase in stress and anxiety in an effort to reorder their lives to fit rigid work reporting requirements.13 What Arkansas’s work requirements failed to address was that many people who are not currently working face significant barriers to employment. More than 16,000 of the 18,000 who lost coverage had not found work by March of this year.14

Using the current findings from Arkansas that 23 percent of those subject to the work reporting

requirements lost coverage, we conservatively estimate that 88,000 North Carolinians could lose coverage.

In the end, this loss in coverage will derail people’s ability to lead healthier lives. Work reporting requirements will not result in job creation or fundamentally address the barriers to employment for those few in the coverage gap who aren’t working but able to work.15 For these North Carolina workers, the fundamental challenge of the labor market is that there are too few jobs for those who want to work and the job growth is concentrated in very low wage occupations in many communities.

Premium payment requirement is likely to compound the effect

The coverage losses from work requirements does not take into account the additional impact in North Carolina of the required premium payments. The same bill contains an additional provision that requires North Carolinians living in the coverage gap and thus with incomes that are too low to afford the basics in North Carolina to pay 2 percent of their annual income in premiums. It provides just a 90 day grace period to catch up on payments or lose coverage with the possibility of regaining coverage only possible if the unpaid premium amount is paid in full.

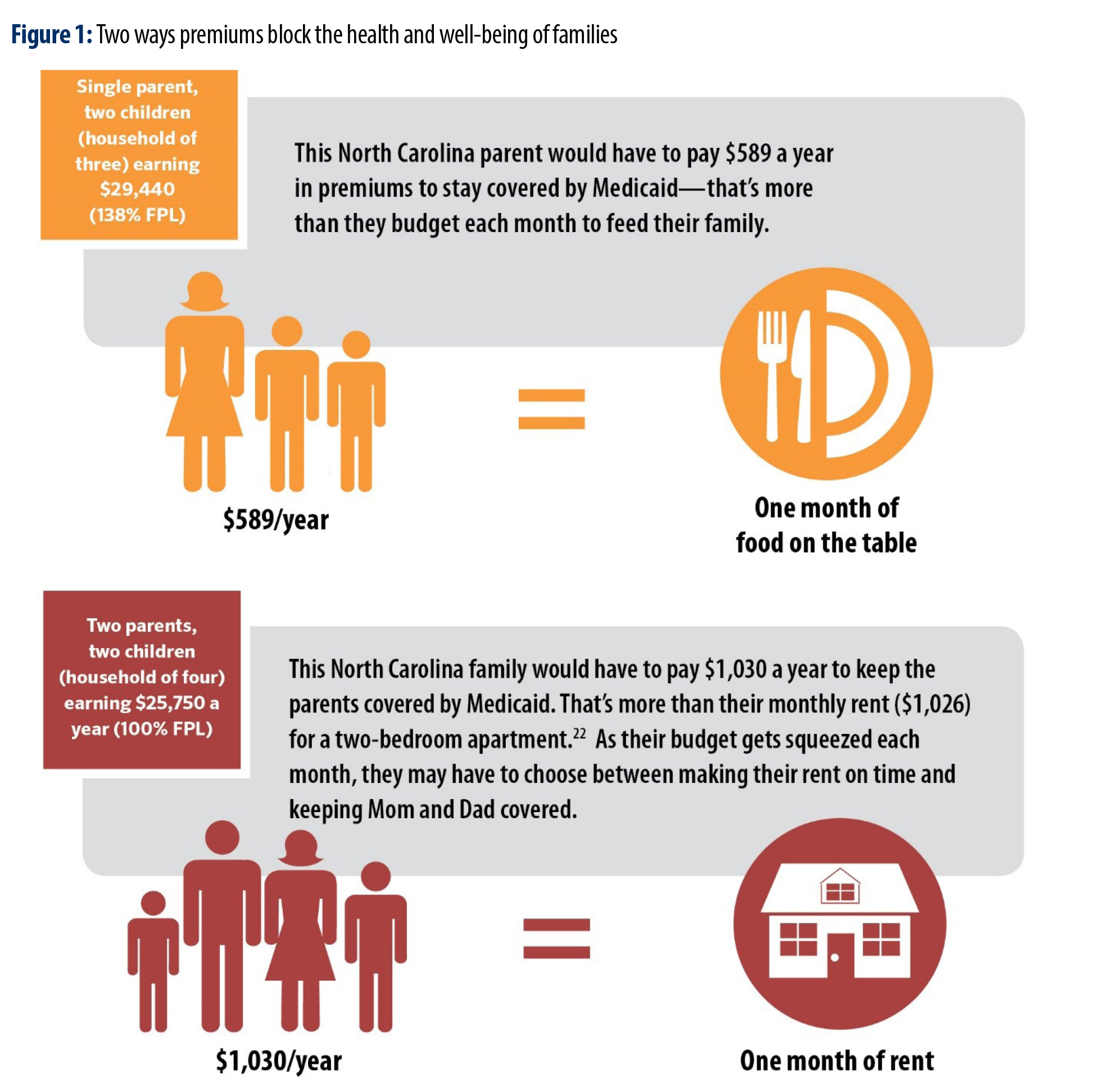

Premium payments present an additional barrier to access as all North Carolinians living in the coverage gap by virtue of their limited income which results in financial hardship in making ends meet (See Figure 1).16 In a household budget where most North Carolinians in the coverage gap are already spending more than recommended levels on housing and child care, and are thus considered cost-burdened, the 2 percent of annual income required in premiums is likely to lead to lower enrollment and loss of coverage.

In addition to the clear challenge to affordability of a premium, there is also emerging evidence that premiums and how they operate can signal to North Carolinians that this is an option that is out of reach for them. The field of behavioral economics is demonstrating the ways in which policy design matters for access and enrollment, and for this discussion finds that beyond price points, the complexity of eligibility requirements and maintenance of participation, as well as the time to manage participation, can serve as additional barriers.17

Studies examining the effects of premiums on low-income populations in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) have found that they are a barrier to obtaining coverage, particularly for those with incomes below the poverty level, and monthly premiums as low as $1 have a negative effect on enrollment.18 As of January 2019, five states required adult Medicaid beneficiaries to pay monthly premiums or other contributions for adult Medicaid beneficiaries, with three of those states (Indiana, Iowa, Montana) receiving a federal waiver to charge premiums to those living below poverty who are not otherwise permitted to be charged. Even in the state of Michigan, where premiums apply to adults above 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), roughly $24,600 for a family of four, and where work requirements do not take effect until 2020, 38 percent of beneficiaries who owed premiums had paid them. And while they cannot be disenrolled from coverage, state income tax refunds can be garnished for consistent failure to pay, affecting over 40,000 beneficiaries.19 The consequences are harsher in Indiana, where in 2016 over 13,000 people were disenrolled from coverage, a full 6.9 percent of all individuals who would have to pay the premium.20 In total, some 29 percent of all individuals who could be disenrolled or not enrolled due to non-payment were either disenrolled or not enrolled. Based on the impact in Indiana, and given that North Carolina’s policy goes beyond Indiana’s to also apply to those between 50 and 100 percent FPL (a fact that we have not accounted for here), a conservative estimate of those who could be affected by the premium proposal, including those who would not to enroll in the first place is 145,000 North Carolinians.21

The North Carolinians harmed by work requirements are our neighbors, coworkers, friends, and family members

Despite the few exemptions from the reporting requirements and due to the ways in which work reporting requirements have led to coverage loss, it is likely that the imposition of these requirements as a condition to access health insurance for those most in need will lead to coverage losses for a wide range of North Carolinians. Exemptions alone cannot fix the policy, and its effects will hurt people playing critical roles in our families and communities as caregivers, protectors, contributors and leaders.

The following overview presents a summary of analysis conducted by the Center on Budget & Policy Priorities on the effect of work reporting requirements on different populations.22

- Rural Residents face higher unemployment than in metropolitan areas, and many who are

able to find employment work variable hours and involuntary part-time work – in farming,

manufacturing and retail – that would make it challenging to meet the required minimum

hours each month. - Many Veterans experience chronic conditions, severe mental illness, substance use

disorders, and other complex conditions that create barriers to stable employment, and many

veterans are ineligible or unable to access VA benefits. - Children are less likely to receive health insurance coverage when their parents are not

covered, therefore putting barriers in place for parents means that children are less likely to

be enrolled in coverage for which they are already eligible. - People with Disabilities may still be subject to work requirements because the diagnoses

and paperwork required to document a disability are complex and out of reach, placing this

population at risk of coverage due to an inability to prove their disability. - People with Mental Health Disorders sometimes do not qualify for exemptions and often

have difficulty proving their disorder because of the Trump Administration’s strict definition of

“medically frail”. - People with Substance Use Disorders often times do not have a qualifying physical

or mental disability. In states that expanded Medicaid, the number of uninsured people

hospitalized with a substance use disorder decreased from 20 percent to 5 percent. - People who are Homeless are more likely to have a disability than the general population

but often have a difficult time providing the proper paperwork. Additionally, people

experiencing homelessness face significant barriers to employment, such as inconsistent

work history and physical or mental health issues.

For North Carolina to reach its full potential as a state, connecting more people to the tools to live healthy lives is critical. Work requirements will entangle too many North Carolinians in costly and unnecessary reporting that won’t improve their employment opportunities and will put at risk their health and well-being.

Work requirements ignore the realities of the labor market

While employment provides a pathway to healthier lives and health insurance coverage has been demonstrated to improve employment outcomes, work-reporting requirements create barriers that make it less likely that these benefits will be fully realized.

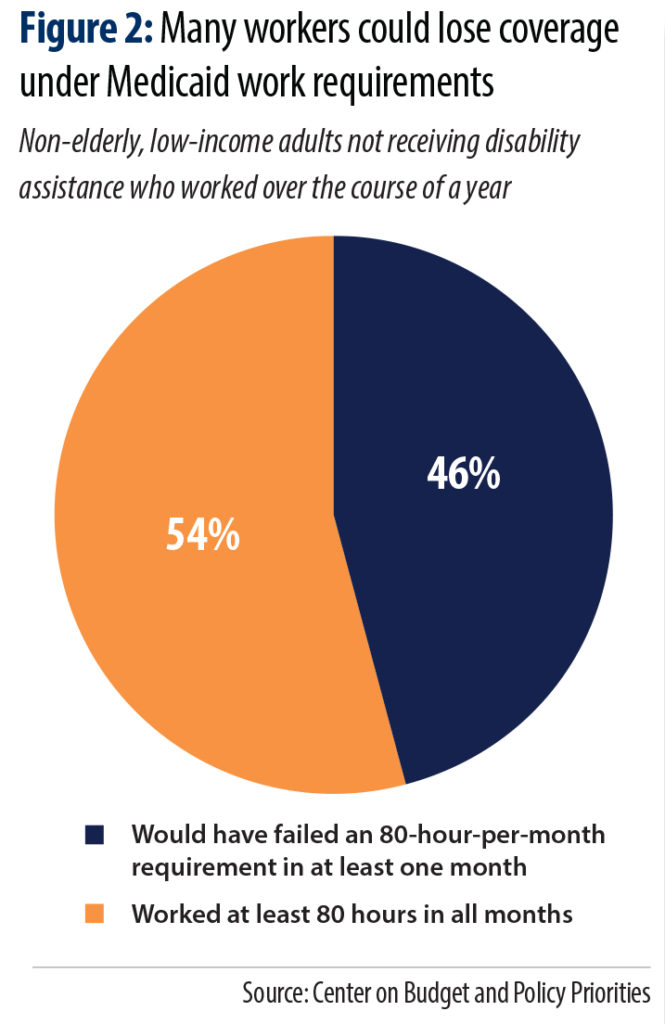

Perhaps most important to the discussion of work reporting requirements is an understanding of the labor force participation of those in the coverage gap. Research has consistently showed that the vast majority of those receiving Medicaid who can work are working.23 Those who have jobs are often working in low-wage, part-time jobs with unpredictable schedules. National data finds that, as evidenced in Figure 2, nearly half (46 percent) of non-elderly adults who do not receive disability assistance and have worked in the past year and earn incomes to qualify for coverage, would not be able to meet the monthly reporting requirements.24 These workers have highly variable work schedules that make their hours worked each month difficult to predict and to meet rigid thresholds set out in work reporting requirements. These workers would fail to meet the 80 hours worked a month threshold in at least one month.

Perhaps most important to the discussion of work reporting requirements is an understanding of the labor force participation of those in the coverage gap. Research has consistently showed that the vast majority of those receiving Medicaid who can work are working.23 Those who have jobs are often working in low-wage, part-time jobs with unpredictable schedules. National data finds that, as evidenced in Figure 2, nearly half (46 percent) of non-elderly adults who do not receive disability assistance and have worked in the past year and earn incomes to qualify for coverage, would not be able to meet the monthly reporting requirements.24 These workers have highly variable work schedules that make their hours worked each month difficult to predict and to meet rigid thresholds set out in work reporting requirements. These workers would fail to meet the 80 hours worked a month threshold in at least one month.

Work reporting requirements are more likely to result in people losing health insurance coverage not because they are not eligible but because of failure to report work activities properly.25 The challenges documented in Arkansas, where work reporting requirements have been implemented, shows that there is a high cost, both administratively and individually, to informing people of the requirement, consistently and accurately recording qualifying activities, and maintaining connections to individuals receiving Medicaid.26

Evidence from other federal programs shows not only do work requirements not help to get people back to work, they put them at risk of losing critical resources that create a foundation to sustainable employment. Recent studies on the impact of work requirements in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program demonstrate that work requirements harm individuals who already face significant obstacles to employment and produce very few lasting effects on increasing employment.

In TANF, for example, many states are bogged down in administrative paperwork and as a result, incorrectly apply work requirements. One study found that nearly 30 percent of sanctions imposed by the state of Tennessee were errors.27 Additional studies found that parents lost benefits due to work requirements even though they faced significant barriers to employment and may have qualified for exemptions.28

Research on work requirements in TANF have also found that while they have reduced the number of people participating in the program, it has not demonstrated long-term or meaningful gains in employment. In fact, an Illinois study found that parents subject to work-requirement related sanctions were 44 percent less likely to have a job than their colleagues not subject to the requirements.29 Researchers even found that long-term TANF recipients subject to work requirements fell into even deeper poverty than before they were subject to the sanctions.30

Our nation’s food assistance program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), provides additional lessons on the real life impacts of work requirements. Of SNAP recipients subject to work requirements, many face significant barriers to engaging in work that include homelessness, physical and mental health issues, language barriers, or caregiving responsibilities for loved ones. A study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that after leaving the SNAP program, although 41 to 76 percent of people found jobs, they only earned between $350 and $1,000 a month31—not nearly enough to support one’s self. Between 17 and 34 percent of people reported skipping meals after being kicked off the program, and 30 to 40 percent reported being unable to pay rent, having to move in with relatives, or even becoming homeless.32

Work requirements can’t be fixed

The inclusion of a work requirement in HB 655 means the bill, if enacted, would not fully close the state’s coverage gap. Due to the complex nature of the labor market, structural barriers to employment that persist in our state —including too few jobs in many communities for those who want to work—and the administrative costs and requirements mean that work reporting requirements could actually do even more harm to families and the broader economy.

As research has shown, work-reporting requirements have not driven improvements in poverty rates nor delivered a broader economic boosts to states that have adopted them.33

Researchers have found, however, that their costs ripple through communities, including the litigation costs that will need to be covered by taxpayers given the illegality of applying a work standard that runs counter to the purpose of Medicaid,34 the harm to hospital finances, and the opportunity costs from diverted taxpayer dollars in order to implement reporting requirements. The costs to taxpayers and all North Carolinians are real and will affect us all.35

Failure to fully cover those in the coverage gap by establishing a work-reporting requirement is likely to generate difficulty for compliance in places where labor markets still have too few jobs, where transportation networks and administrative offices are difficult to access. This means it would likely affect many rural communities where providers and hospitals are more likely to be considered at high financial risk.

The reality is that work-reporting requirements can’t be fixed36 and will leave ahead for future leaders the high rates of uninsurance in North Carolina that compromise the health and well-being of each of us.

Footnotes

- Antonisse, Larisa, et. al. (2018). The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a

Literature Review. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: http://files.kff.org/attachment/

Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings - Antonisse, Larisa and Rachel Garfield (2018). The Relationship Between Work and Health: Findings from a Literature

Review. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/

the-relationship-between-work-and-health-findings-from-a-literature-review - Tucker, Whitney and Fumi Agboola (2019). Expanding Healthcare to Shrink Poverty. NC Child: Raleigh, NC. Accessed

here: https://www.ncchild.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019_Brief_MedEx-FinancialStability_FINAL.pdf

and Antonisse, Larisa and Rachel Garfield (2018). The Relationship Between Work and Health: Findings from a

Literature Review. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/

issue-brief/the-relationship-between-work-and-health-findings-from-a-literature-review/ - Goodnough, Abby (2019). Judge Blocks Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas and Kentucky. New York Times:

New York, NY. Accessed here: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/27/health/medicaid-work-requirement.html - Mitchell, Tazra (2018). Promising Policies Could Reduce Economic Hardship, Expand Opportunity for Struggling Workers. Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/promising-policiescould-

reduce-economic-hardship-expand-opportunity - Munn, William (2019). Employment growth is not equitable across North Carolina counties. NC Budget & Tax Center: Raleigh, NC.

Accessed here: https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/employment-growth-is-not-equitable-across-north-carolina-counties/ - National Equity Atlas (2017). Indicators: Working Poor. PolicyLink: Oakland, CA. Accessed here: https://nationalequityatlas.org/

indicators/Working_poor/Full-time_workers_by_poverty:40291/North_Carolina/false/Year(s):2015/ - Bolen, Ed, et. al. (2016). More Than 500,000 Adults Will Lose SNAP Benefits in 2016 as Waivers Expire. Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/more-than-500000-

adults-will-lose-snap-benefits-in-2016-as-waivers-expire - U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents (ABAWDs). Accessed here:

https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/ABAWD - Musumeci, MaryBeth, Robin Rudowitz and Barbara Lyons (2018). Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and

Perspectives of Enrollees. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaidwork-

requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-enrollees-issue-brief/ - Ibid

- Wagner, Jennifer (2019). Commentary: As Predicted, Arkansas’ Medicaid Waiver Is Taking Coverage Away From Eligible People. Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/health/commentary-as-predicted-arkansasmedicaid-

waiver-is-taking-coverage-away-from-eligible-people#_ftn11 - Musumeci, MaryBeth, Robin Rudowitz and Barbara Lyons (2018). Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and

Perspectives of Enrollees. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaidwork-

requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-enrollees-issue-brief/ - Wagner, Jennifer (2019). New Arkansas Data Contradict Claims That Most Who Lost Medicaid Found Jobs. Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/blog/new-arkansas-data-contradict-claims-that-most-who-lostmedicaid-

found-jobs - Rachidi, Angela (2018). The truth about Medicaid work requirements. American Enterprise Institute: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: http://www.aei.org/publication/the-truth-about-medicaid-work-requirements/

15. Riley, Brendan (2019). Health Coverage or Food on the Table? North Carolinians Face Impossible Choices if Medicaid Expansion

Requires Premiums. North Carolina Justice Center: Raleigh, NC. Accessed here: https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/healthcoverage-

or-food-on-the-table/ and Artiga, Samantha, et. al. (2017). The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income

Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.

org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-researchfindings/- Chernew, M., et. al. (1997). The demand for health insurance coverage by low-income workers: can reduced premiums achieve full

coverage? Health Services Research: Chicago, Il. Accessed here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9327813/ and Baicker, Katherine, et. al. (2012). Health Insurance Coverage and Take-Up: Lessons from Behavioral Economics. The Milbank Quarterly. Accessed here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3385021/ and Neuert, Harrison, et. al. (2019). Work Requirements Don’t Work – A behavioral science perspective. Ideas42: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: http://www.ideas42.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ideas42-Work-Requirements-Paper.pdf - Artiga, Samantha, et. al. (2017). The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research

Findings. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-ofpremiums-

and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/ - Musumeci, MaryBeth, et al. (2017). An early look at Medicaid expansion waiver implementation in Michigan and Indiana. Kaiser Family

Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-early-look-at-medicaid-expansionwaiver-

implementation-in-michigan-and-indiana/ and State of Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Michigan

Adult Coverage Demonstration – Section 1115 Quarterly Report. Accessed here: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-

Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/mi/Healthy-Michigan/mi-healthy-michigan-qtrly-rpt-09202016.pdf - The Lewin Group (2017). Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER Account Contribution Assessment. Accessed here: https://www.medicaid.

gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plansupport-

20-POWER-acct-cont-assesmnt-03312017.pdf - Author’s calculation taking the 29 percent from Indiana and applying that to the estimated coverage gains from Medicaid Expansion of

500,000. The North Carolina proposal (HB655) does not require people with incomes below 50 percent FPL to pay premiums but all other

new Medicaid eligibles are subject to the requirement unless they have a medical or financial hardship, are an Indian Health Services

beneficiary, or if they are a veteran in transition but are actively seeking employment. - Medicaid Briefs: Who is Harmed by Work Requirements? (2019). Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D. C. Accessed here: https://

www.cbpp.org/medicaid-briefs-who-is-harmed-by-work-requirements - Katch, Hannah, et. al. (2018). Taking Medicaid Coverage Away From People Not Meeting Work Requirements Will Reduce Low-Income

Families’ Access to Care and Worsen Health Outcomes. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here:

https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirements-will-reduce-low-income-families-access-to-care-and-worsen - Solomon, Judith (2019). Medicaid Work Requirements Can’t Be Fixed. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C.

Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirements-cant-be-fixed - Garfield, Rachel, et. al. (2018). Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses. Kaiser

Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA. Accessed here: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-a-medicaid-workrequirement-

national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses/ - Wagner, Jennifer (2019). Commentary: As Predicted, Arkansas’ Medicaid Waiver Is Taking Coverage Away From Eligible People. Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/health/commentary-as-predicted-arkansasmedicaid-

waiver-is-taking-coverage-away-from-eligible-people#_ftn11 - Goldberg, Heidi and Liz Schott (2000). A Compliance-oriented Approach to Sanctions in State and County TANF Programs. Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/archiveSite/10-1-00sliip.htm - Pavetti, Ladonna (2018). TANF Studies Show Work Requirement Proposals for Other Programs Would Harm Millions, Do Little to

Increase Work. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/familyincome-

support/tanf-studies-show-work-requirement-proposals-for-other-programs-would#_ftn5 - Lee, Bong Joo, Kristen S. Slack, and Dan A. Lewis (2004). Are Welfare Sanctions Working as Intended? Welfare Receipt, Work Activity

and Material Hardship among TANF-Recipient Families. Social Service Review, September 2004, pp. 371-402. - Pavetti, Ladonna (2016). Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington,

D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows - Dagata, Elizabeth M. (2002). Assessing the Self-Sufficiency of Food Stamp Leavers. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of

Agriculture. Accessed here: www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=46645 - ibid

- Pavetti, Ladonna (2016). Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C. Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows

- Yearby, Ruqaiijah (2018). Medicaid Work Requirements: Are They Illegal and Will They Increase Poverty? Jurist – Legal News &

Research: Pittsburgh, PA. Accessed here: https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2018/02/ruqaiijah-yearby-medicaid-poverty/ - Haught, Randy, Allen Dobson, and Phap-Hoa Luu (2019). How Will Medicaid Work Requirements Affect Hospitals’ Finances? The

Commonwealth Fund: New York, NY. Accessed here: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/mar/howwill-

medicaid-work-requirements-affect-hospitals-finances - Solomon, Judith (2019). Medicaid Work Requirements Can’t Be Fixed. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington, D.C.

Accessed here: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirements-cant-be-fixed

Justice Circle

Justice Circle