Over the past decade, North Carolina’s revenue has become more regressive as growth in revenue from fines, fees, and sales tax has outpaced growth in corporate income and individual income tax revenue. This shift is the effect of state policy decisions that have asked those with the greatest economic resources in our state — wealthy individuals and corporations — to contribute less and have asked North Carolinians with less ability to pay to contribute more. As state agencies cope with lost fee revenue during the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers must take this opportunity to correct course and move away from an increasing reliance on inadequate and inequitable revenue sources.

Growth in fee revenue is outpacing other revenue sources in North Carolina

From FY 2011-12 to FY 2017-18, state agencies’ fee revenue increased 26 percent in North Carolina. Growth in fines and fees outpaced growth in individual income tax revenue, which increased 22 percent, and far exceeded growth in corporate income tax revenue, which decreased 35 percent. Revenue from sales and use taxes increased 40 percent over the same period (Figure 1).

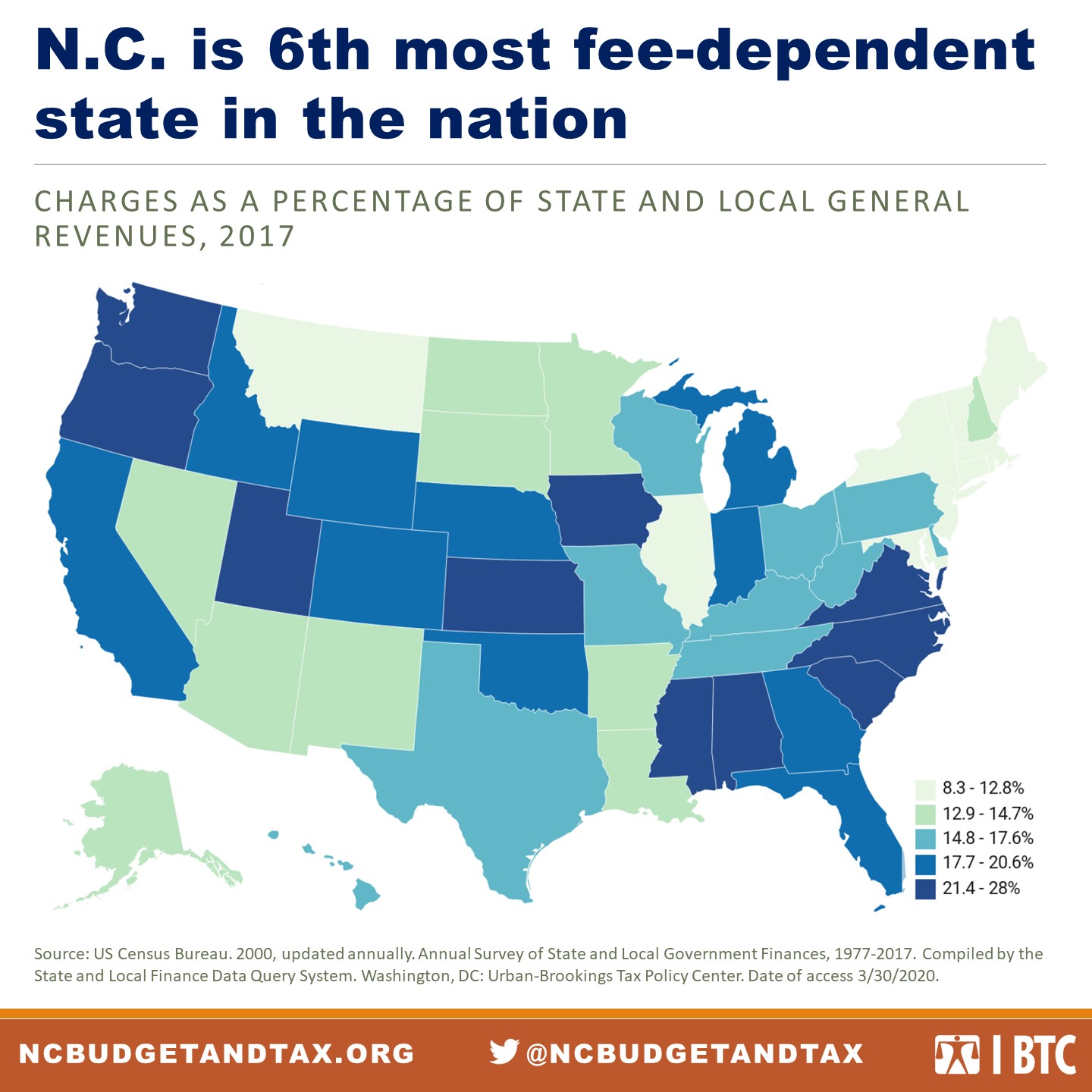

This increasing reliance on fines and fees is not limited to North Carolina. Research from the Urban Institute has shown that, of all major sources of state and local revenue, fees (also known as charges) have seen the greatest percentage increase nationwide over the last 40 years — a whopping 303 percent in real dollars. In state and local governments across the country, charges brought in approximately as much revenue as property taxes in 2017, and charges exceeded the revenue generated from sales taxes and individual income taxes.

The appeal of fines and fees to policymakers is straightforward: Imposing user fees (and then raising them over time) allows lawmakers to avoid unpopular spending cuts and tax hikes. These charges nevertheless raise several concerns that should give policymakers and taxpayers pause. Firstly, reliance on fines and fees often limits a government’s ability to sustain investment over time. With local governments limited by state law in their taxation powers, cities often turn to fines and fees to make up the difference when state tax policy fails to raise adequate revenue for community needs. Nationwide, the most fine-dependent jurisdictions in 2019 were those that had seen the steepest cuts in state funding over the previous decade.

Fees are also an inherently inequitable source of revenue: In failing to account for ability to pay, these charges hit low-income North Carolinians the hardest. A $230 speeding ticket would be an annoyance for the wealthiest among us, but for many North Carolinians, an initial inability to pay can spiral into a revoked license, mounting court debts, and a lifelong battle with the criminal justice system.

Finally, the use of fines and fees in our country and state are inextricable from systemic racism. Nationwide, places that most rely on fines and fees are more likely to have large Black populations. A 2015 investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice famously found that the Ferguson (Missouri) Police Department disproportionately targeted Black residents in its law enforcement efforts with the explicit goal of using fine and fee collections to fund general city operations rather than public safety. North Carolina’s criminal justice system similarly raises general revenue through the criminalization of poverty and Black and Brown residents: Less than 1 percent of revenue collected by the Judicial Branch remains with the court system, while 35 percent of disbursements are sent to the state treasurer, other state agencies, and law enforcement retirement funds.

Underlying shortcomings of reliance on fines and fees are exacerbated in the context of COVID-19

As North Carolina policymakers are well aware, the current pandemic is wreaking havoc on state revenue sources across the board. The recently released consensus revenue forecast predicts a $4.2 billion shortfall in state collections. Although forecasters were unable to make line-item predictions due to unprecedented levels of uncertainty, the Legislative Fiscal Division reports that reduced sales tax collections are largely driving the shortfall this year, while the impact of reduced income tax collections will be felt next year.

State agencies dependent upon fines and fees are in the difficult position of trying to provide temporary fee relief to clients, while also coping with the uncertainty of lost or delayed revenue. The Judicial Branch — which collected about $264 million in fines and fees in FY 2017-18 — issued an executive order extending the due date for fines and fees for 90 days. The N.C. Fines & Fees Coalition has petitioned lawmakers to repeal or suspend statutes that impose court fines and that penalize North Carolinians for failure to pay, emphasizing that temporary relief is insufficient within a revenue system that deliberately relies most heavily on those least able to pay.

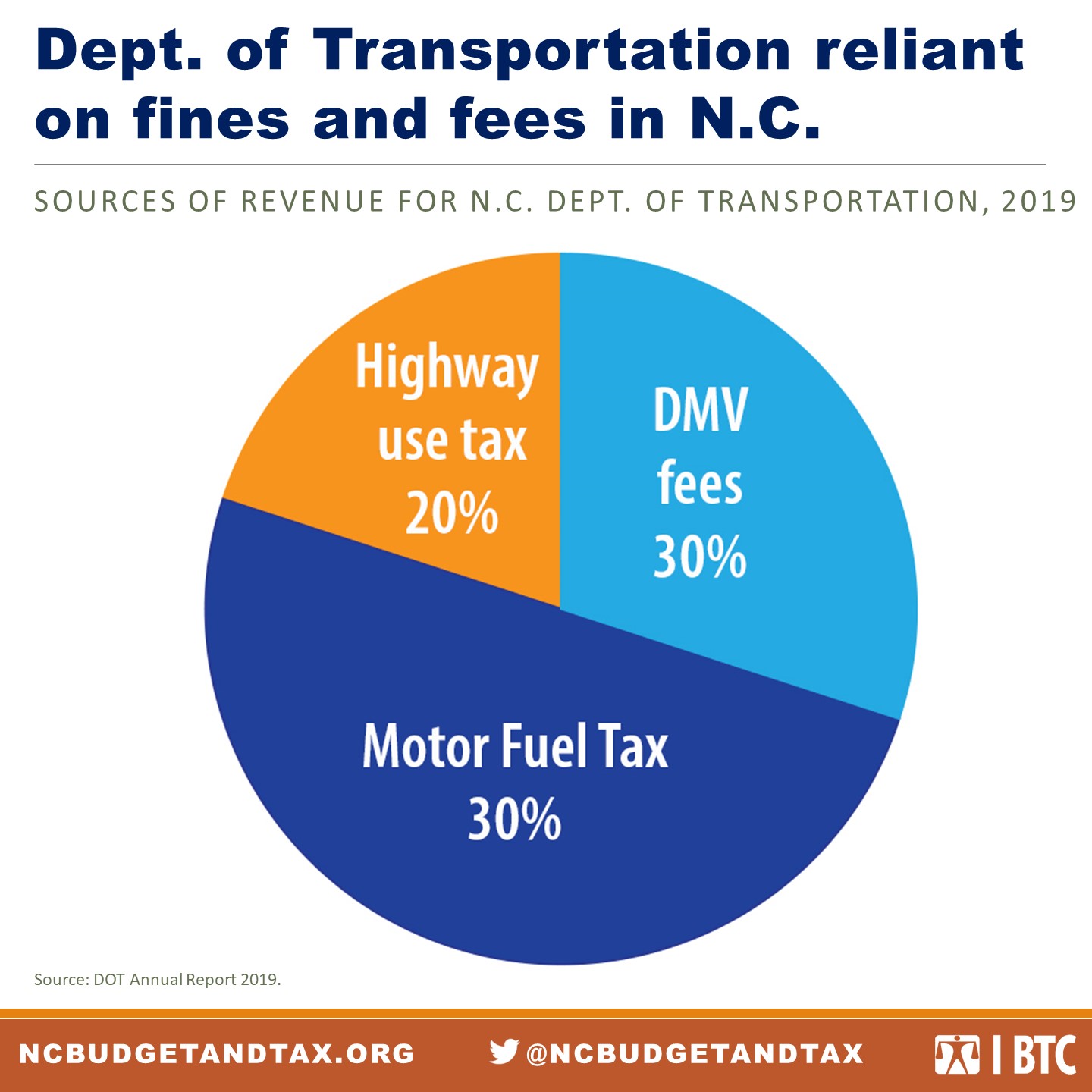

COVID-19 is also exacerbating pre-existing issues with the Department of Transportation’s revenue streams. In annual reports dating back to at least 2013, the DOT has raised concerns about the inability of its user-dependent state revenue sources — the Motor Fuel Tax, DMV fees, and the Highway Use Tax — to keep up with the needs of a growing population. In the context of the pandemic, the department has temporarily waived any fines and fees related to expired credentials such as driver’s licenses and vehicle registration tags.

DMV fees account for approximately 30 percent of state DOT funding (Figure 3). The consensus revenue forecast projects a $774 million shortfall for the DOT over the 2019-2021 fiscal years due to waived fees and because fewer North Carolinians are driving and filling up their gas tanks. The agency has already furloughed its top executives in response.

Fees, COVID-19, and higher education

While fines and fees in the criminal justice system have rightly been a focus of research and advocacy work in North Carolina, these user charges are not confined to the court system and DMV offices. The University of North Carolina System collected the most fee revenue of any state department in FY 2017-18 at $3.7 billion, more than three times as much as the next-highest department. Tuition and fees accounted for almost two-thirds of that sum.

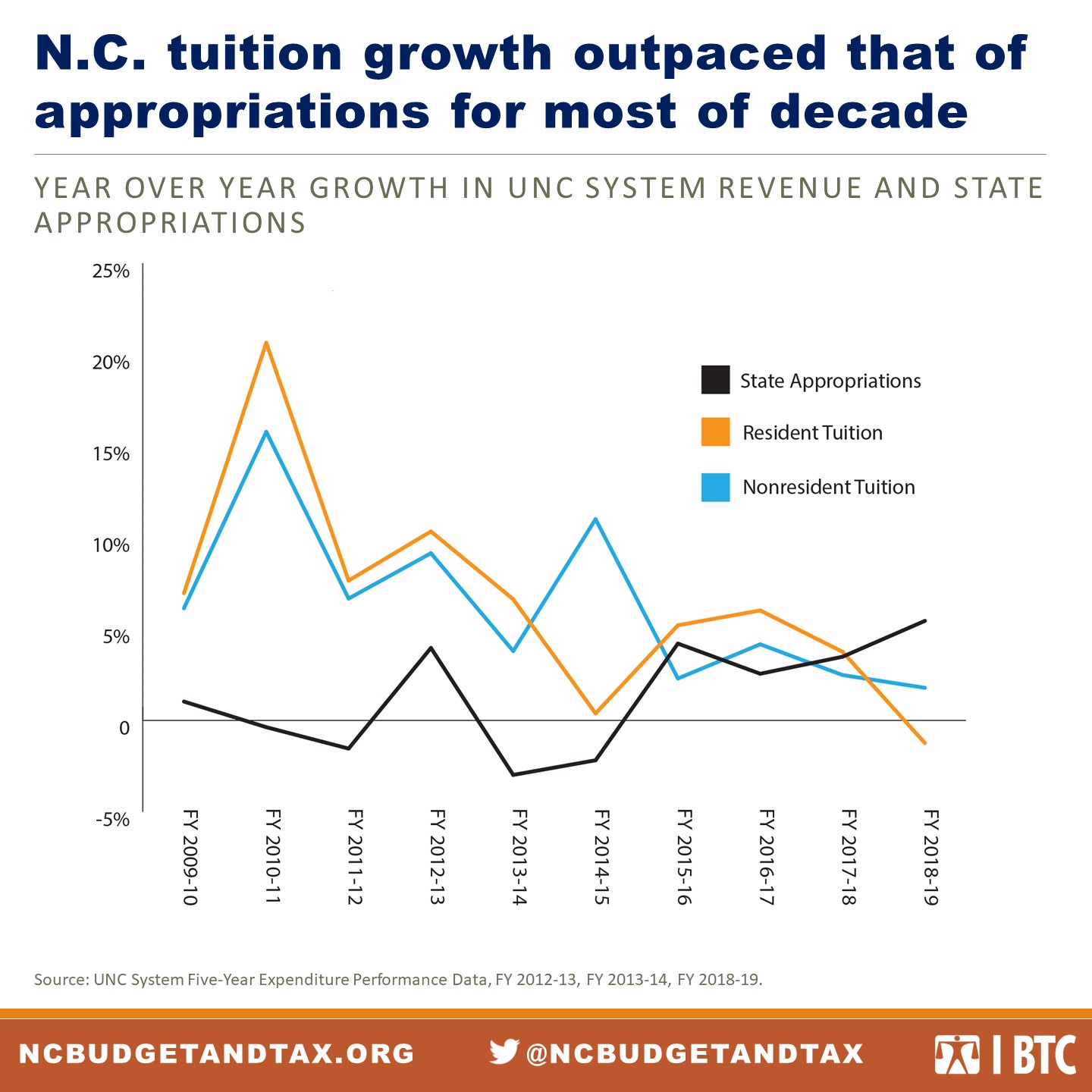

The UNC System’s reliance on student tuition and fees is a striking example of North Carolina’s inequitable shifting of the tax burden. Over the past decade, tuition has increased far more quickly than state appropriations to the UNC System. Since the Great Recession, state appropriations have increased only 14 percent, while resident tuition revenue has increased 87 percent. State appropriations decreased as recently as FY 2014-15 — the same year that the state’s lower corporate income tax rates and flat individual income tax rates took effect.

The consequence of these policy decisions has been to shift the burden of paying for higher education to students and their families, despite a state constitution requiring that higher education, “as far as practicable, be extended to the people of the State free of expense.”

In the context of COVID-19, out-of-pocket expenses combined with a modified learning environment may have some students reconsidering their enrollment this fall. The UNC System has announced that it will freeze tuition and fees for the next school year. While this is welcome news for families who cannot afford hikes, the system’s finances face great uncertainty. Faculty and students at UNC-Chapel Hill have expressed concern that the need for tuition revenue is driving the school’s decision to return to in-person classes before it may be safe to do so.

N.C. public institutions need equitable sources of revenue

North Carolina is increasingly reliant on regressive forms of taxation that fall disproportionately on low-income residents and people of color. The elimination of the graduated individual income tax and the reduction of corporate tax rates have caused the state to forgo huge sums of revenue desperately needed for public investments in health, education, and infrastructure. At the same time, policymakers have endorsed a reliance on fines and fees. These charges show up everywhere — from our courts to our transportation system to our institutions of higher education — and have made North Carolina one of the most fee-dependent states in the nation.

COVID-19 has exposed the hazards of fine and fee dependency in North Carolina and presents an opportunity to rethink how we fund our state and local governments. In the short-term, state policymakers must cope with reduced fine and fee collections by looking to other, more equitable sources of revenue. A tax on corporate profits would put North Carolina more firmly on the path toward recovery, by ensuring that businesses that continue to thrive during the pandemic are contributing to the public infrastructure that fuels our state’s economy. Equitable investment in people who are most in need will keep our communities resilient during the pandemic and lay the groundwork for a strong and speedy recovery.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle