Prosperity Watch, Issue 88, No. 4

(July 25, 2018)

New research from the Economic Policy Institute finds that infrequent adjustments to the federal minimum wage have eroded the value of work and left many more living in poverty despite their hard work. In North Carolina, nearly 1 in 8 working families (126,000) live below the federal poverty level in the state according to the Working Poor Families Project.

Researchers adjusting the 1968 minimum wage for inflation find that a full-time minimum wage worker would have earned roughly $10 an hour or $20,600 a year in 2017 dollars. Yet a worker paid the federal minimum wage in 2017 could only earn $15,080 working full time.

This falls below the federal poverty level for a worker with one child ($16,543) and far below what it takes to make ends meet in North Carolina for the same family size ($35,710).

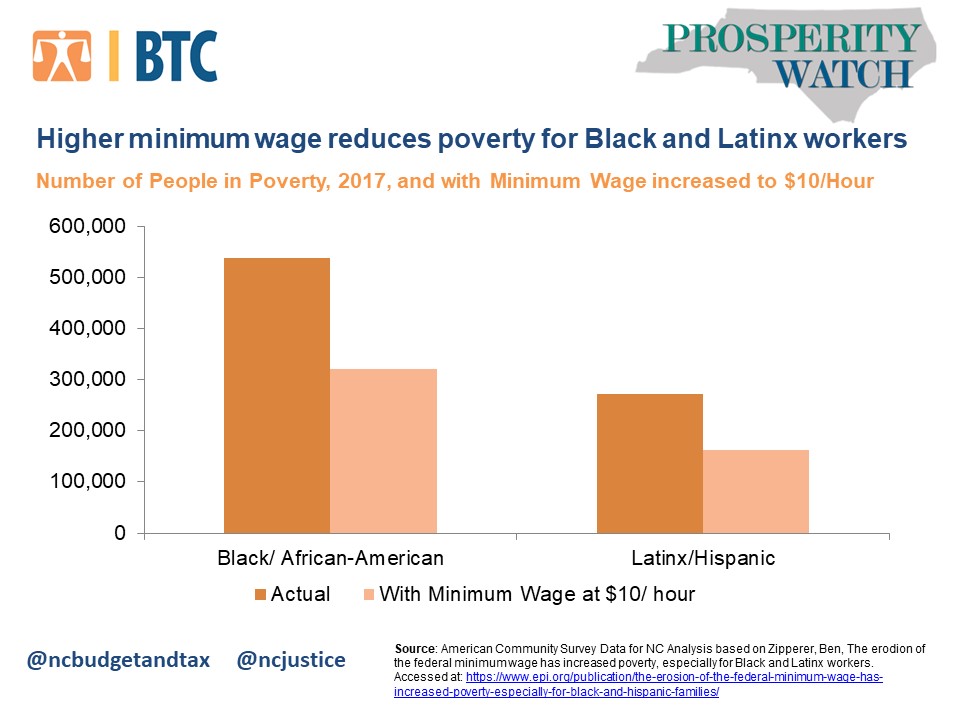

Boosting the minimum wage to its value in 1968 would have a significant benefit to all workers and particularly workers of color. That is because workers of color are more likely to be paid hourly wages, engaged in part-time work and working in industries whose pay is at or close to the minimum wage. The reasons that Black and Latinx workers are more likely to find this type of employment is connected to historic barriers to opportunity, systems that have excluded certain employment from wage standards and ongoing discrimination in the labor market.

Given research on the effect of the minimum wage on poverty nationally that finds a minimum wage increase serves as a nearly equivalent countervailing force against poverty for Black and Latinx workers, Economic Policy Institute researchers found that nearly 3.3 million African Americans and Hispanics would no longer be in poverty had the value of work today earned a minimum wage equivalent to that earned in 1968.

For North Carolina, a similar boost to the minimum wage for state workers would increase the number of Black and Latinx workers living above the poverty threshold by an estimated 328,000.

The poverty-reducing effects of raising the minimum wage would likely taper off as the minimum wage got closer to $15, simply because at those higher wage levels, fewer workers are in poverty to begin with. But, if continuing to raise the minimum wage from $10 to $15 reduced poverty by just 1 more percentage point that would mean 92,000 fewer NC workers would be in poverty.

Although we cannot predict the limits to the power of minimum wage increases in reducing poverty, it is clear that more workers earning an income that allows them to meet basic needs boosts the broader economy by increasing demand for goods and services and stabilizing families.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle