Communities across North Carolina are experiencing rapid gentrification and the displacement of residents that often follows. While some urban renewal, community reinvestment, and economic development efforts can change a place without forcing residents to relocate, these efforts also have a racist legacy of intentionally pushing people of color out of their communities. Whatever the intent, both public and private investments often have the effect of displacing low-income residents. However, defining gentrification and predicting which communities will gentrify and when is an imperfect science. Researchers have adopted various methodologies to study cities like Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Boston, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and New York City, looking at factors such as existing public transportation systems, job growth, and changes in income and other demographics.

Regardless of how we define gentrification, far too many North Carolinians have already been displaced by rising rents, mortgages, and property taxes, or they face being forced out of their neighborhoods — particularly people of color and low-income residents. The consequences of displacement are far-reaching: Families forced to leave their homes and neighborhoods must often spend more of their income on housing and transportation, which undermines their ability to pay for other necessities like food, clothing, and health care. Being displaced can lead to longer commutes, fewer available working hours, and less time with the family. Those without cars or the assets to fix or replace broken vehicles face an additional burden as they are displaced further away from work, public transportation, and community resources.

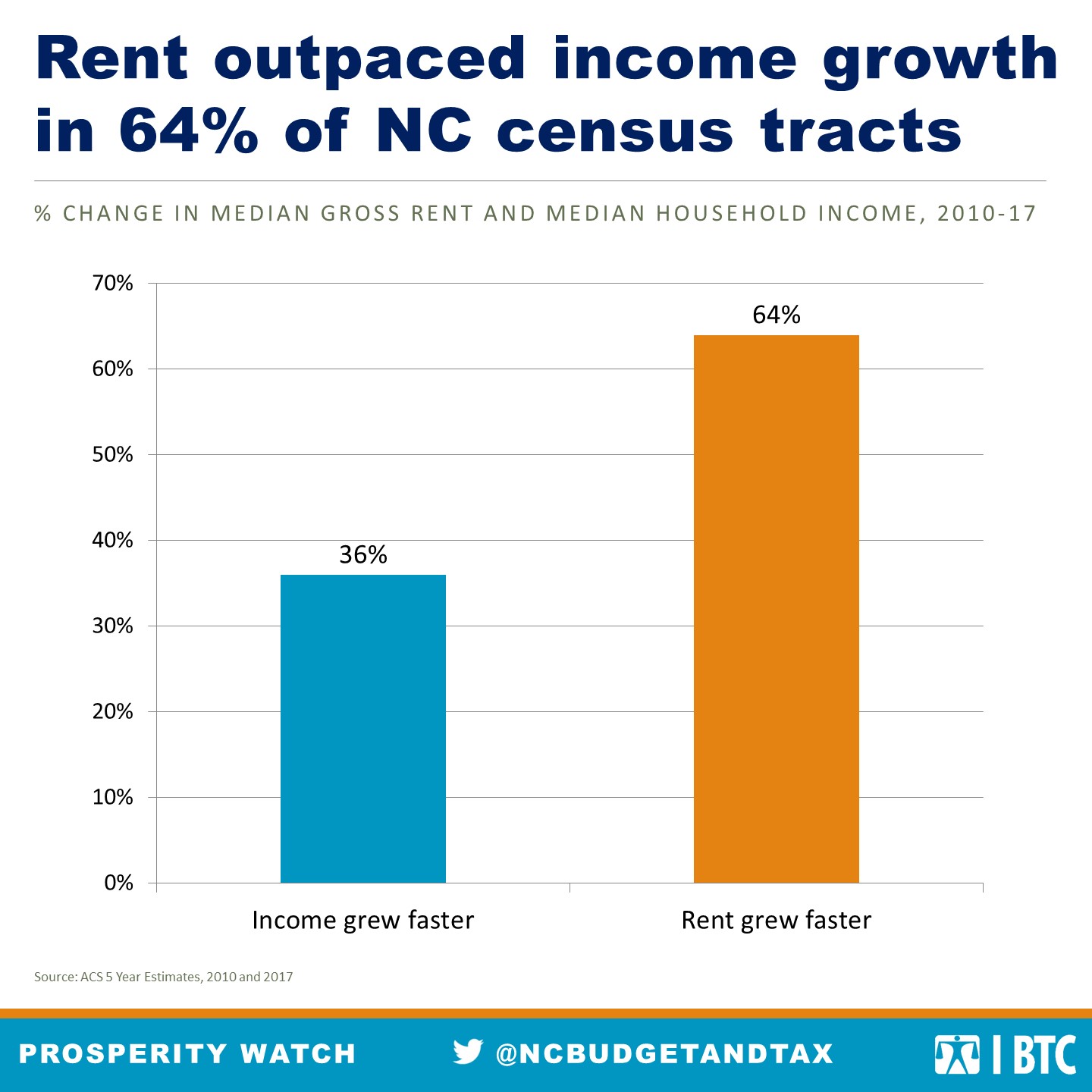

High growth in rents, which well outpace job and income growth, may indicate that a community is already facing displacement. U.S. Census Bureau data show that rent in 64 percent of census tracts in North Carolina rose faster than income. The measure compares the percent changes in median gross rent with median household income between 2010 and 2017. Income reported by the Census Bureau includes that of renters and homeowners, so increases are not necessarily direct increases in the income of renters. For example, 52 percent of census tracts experienced an increase in the percent of income spent on rent. However, the effect of rising housing values and area median incomes likely still drive up rents and may reflect displacement that has already occurred. These statistics reflect the stagnation of many working people’s wages and the rapid rise in housing costs throughout the state, even during a period of economic growth, and paint a particularly grim picture for renters across North Carolina.

Homeowners are also at risk of displacement. Forty-four percent of N.C. census tracts have seen growth in housing values outpace income growth. As values of homes increase, the amount owed in property tax increases as well. Homeowners facing higher property taxes may be forced to sell their homes and relocate.

With little growth in affordable housing and flat wages, North Carolinians are increasingly facing the pressures of gentrification and displacement throughout the state.

Justice Circle

Justice Circle