North Carolina is experiencing substantial population growth, particularly in its cities.[1] More than 60 people a day move to Wake County.[2] The state’s urban economies are growing, but the tide is not lifting all boats. While populations are growing, racial gaps in education, wages, and poverty have persisted or increased. [3] Wages remain stagnant Communities’ demographics are changing as increasingly more well-resourced white people purchase homes and move into low-income neighborhoods.[5] With few protections for the current residents of these communities, a growing portion of the state is facing not just gentrification but the negative effects of displacement of current residents.[6]

Gentrification is generally recognized as the movement of high-income, highly educated white people into low-income urban neighborhoods of color. How gentrification is specifically measured differs across researchers and geographies, but the components are often the same. The influx of affluent white people into low-income communities introduces new capital, creating a broader tax base and leading to racial integration.[7][8] As social and economic capital increases, gentrifying communities often attract more government resources and private investment. While the increased funding and access to resources is beneficial for these urban economies, the process itself can be deeply painful and frustrating for current residents, many of whom have been systematically segregated and isolated by federal, state, and local policies.[9] Meanwhile, communities entrenched with high rates of poverty remain without the resources and investment needed to build opportunities and strengthen their economies. [10] Further, without intervention, the momentum of gentrification often leads to displacement as rents and prices for necessary goods, such as groceries and transportation, rise rapidly without accompanying increases in wages for existing residents.

Increased displacement and segregation is costing the state

The academic literature on gentrification’s effect on displacement is mixed. Researchers have struggled to establish a causal relationship between gentrification and displacement, despite watching community members get priced out of their neighborhoods.[11] that the inconclusive nature of gentrification literature may be due to both the difficulty of accurately measuring both the phenomenon and the resulting displacement.[12] Many communities of color face unstable housing conditions, thus exacerbating the displacement occurring in gentrifying areas.[13]

Neighborhood socio-economic demographics are changing throughout North Carolina. Cities like Charlotte and Raleigh are some of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the U.S., experiencing rapid increases in white populations and displacement of people of color.[14] Working-class communities are being pushed out of “revitalized” neighborhoods.[15] For example, residents of southeast Raleigh’s South Park community fear being priced out of their historic neighborhood.[16] Developers have descended into the community, located south of downtown Raleigh, building and occupying $400,000 homes where vacant lots once stood.[17] While development is generally welcomed, the fact remains that as a result of historic, racialized barriers to opportunity, existing Black residents do not possess the income or wealth that their new affluent white neighbors have accumulated over time. This puts them at great risk of being unable to manage the rising tax value of their own homes and subsequent displacement. Rural communities in western and eastern counties are also changing, becoming second-home communities for out-of-state families[18] Research shows that Black people with ancestral roots in the non-metropolitan South who spent their professional careers in northeastern urban centers are increasingly choosing to retire in those same rural communities.[19]

The displacement of low-income families and communities of color is contributing to a new and insidious form of racial and residential segregation. Foreshadowing of this trend can be found in the state’s two fastest growing counties in southeastern North Carolina, both bedroom communities of Wilmington, a port and urban center.[20] The Black-White segregation index, which measures the degree to which Black people live separately from whites (0 -100, 0 being complete integration and 100 being complete segregation), reveals a marked increase in Pender and Brunswick counties from 2016 to 2019.. These changing patterns of community development create poorer financial, social, and health outcomes for everyone[22] [23]

Recognizing this, North Carolina should strengthen its economy for all residents by both working to eliminate enduring racial wealth and income disparities and crafting policy that prevents displacement for families who wish to remain in their neighborhoods. Research done for the New York Times found that in the South Park community in Raleigh, white homebuyers earn on average $75,000 more than their Black neighbors.[24] This underscores a deep and systemic issue that is a core danger of gentrification. Capital, often inaccessible to communities of color, is readily available for whites, providing flexibility for some and hard choices for others. Identifying and addressing barriers to prosperity while creating access for all will bring stability to those traditionally isolated from equal access. This stabilization will produce opportunity for positive quality of life outcomes for the lives of all North Carolinians, whether Black, brown or white. The generational benefit would be immediate. Research suggests children’s lifetime earnings are substantially diminished every year spent in low-income communities.[25] However, intentional policies that invest equitably in low-income communities would create the rich, diverse environments that provide children the foundation necessary to prosper at the same level as their counterparts who live across town. Just as important would be the innovative and inclusive policy that would prevent disruption and displacement, improving residential well-being and economic futures.

Many policies accelerate growth without community benefit

Various public policies have sought to drive private capital to low-income communities with the perceived mutual benefit of revitalization for residents and profit for investors. However, experience reveals that the design of these programs and the early assessment of the potential negative impact to communities is critical to minimizing harm and maximizing collective benefit. As these policies have been evaluated in hindsight, many have been critiqued for their failure to deliver broadly shared prosperity and grow new opportunities without displacement of existing communities.[26]

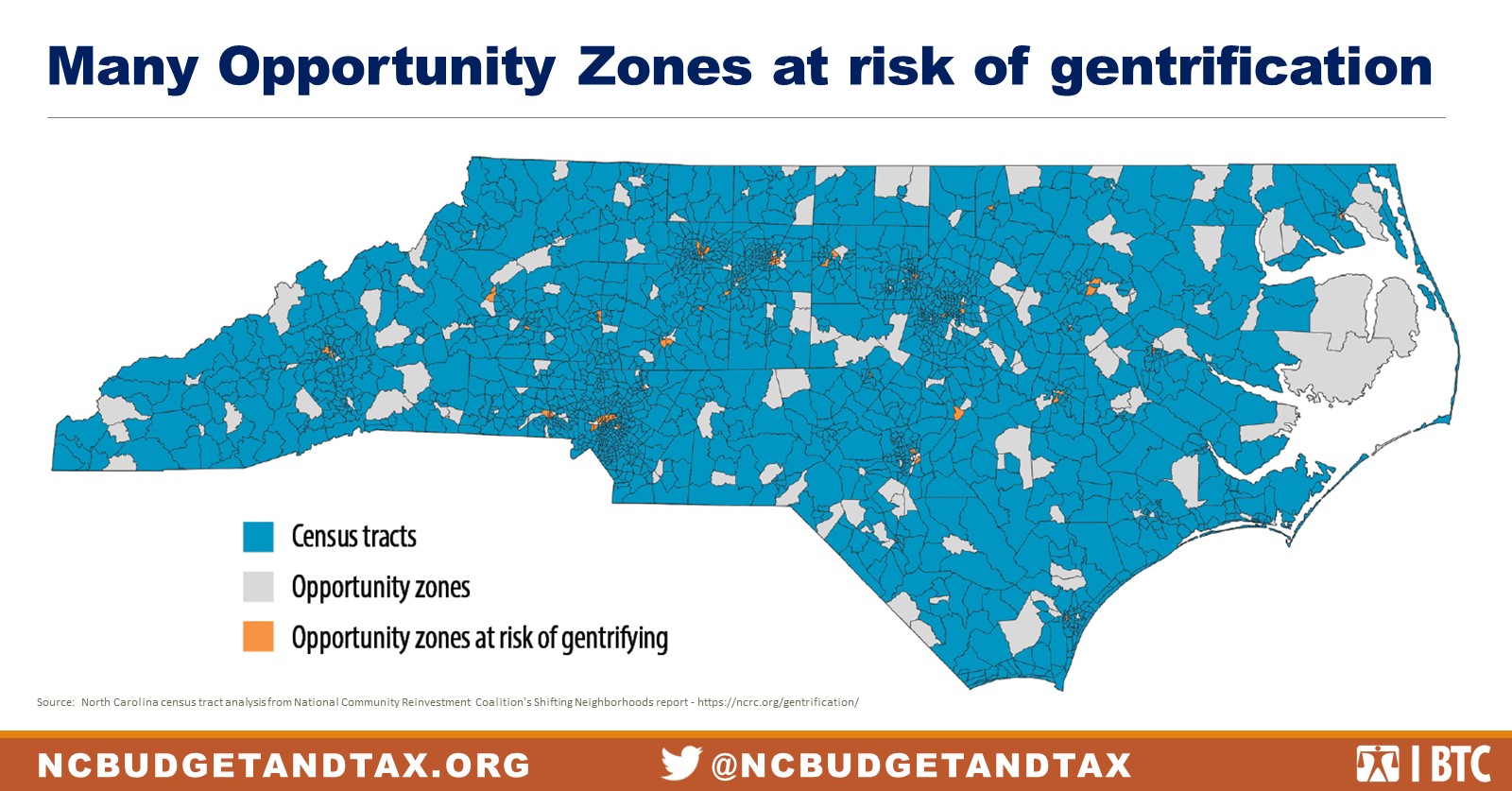

One such policy, passed in December 2017 as part of the Tax Cut and Job Creation Act (HR 1), included provisions that established Opportunity Zones and broad legislative language for their implementation. The goal of these zones is to drive private, long-term capital to distressed census tracts by providing investors tax breaks on capital gains that depend on the length of time they are willing to hold their assets in specially created Opportunity Funds.[27] As such, stakeholders across the country and in North Carolina are monitoring the implementation of Opportunity Zone investments to ensure the maximum benefit to existing residents and the broader community.

However, analysis of the census tracts selected as Opportunity Zones by the Governor and certified by the Internal Revenue Service find that many are at risk of gentrification. Data from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) revealed that, of the North Carolina’s 252 census tracts identified as Opportunity Zones, 69 (or almost 30 percent) were at risk for gentrification in 2012.[29] n fact, the analysis found that Charlotte, Raleigh, Winston-Salem, and Durham collectively saw 14 neighborhoods gentrify in 17 years (2000 – 2017). According to NCRC’s methodology, neighborhoods at risk to gentrify had median home values and family incomes lower than 40 percent of that of their closest metropolitan center (CBSA) in the year 2000. Possible gentrification is determined by including all eligible tracts and then identifying tracts that were in the top 60th percentile for increases in both median home value and the percentage of college graduates.

This analysis would strongly suggest that, as new capital and development follows wealthier homebuyers, one should expect conditions that are ripe for gentrification. Without proper policy consideration, longtime community leaders and homeowners in these communities may face displacement.

There are growing concerns that Opportunity Zones/ Funds will not prioritize collective community benefit. Congressional leaders are calling the integrity of the policy into question as evidence emerges that the actualized benefit is being prioritized for the wealthy and connected.[31] In order to avert displacement, public policy must include equity and inclusion as a foundation to ensure that capital gains benefits, a larger tax base, new development and upscale neighborhoods are not the narrow focus of decision makers.

Given the evidence of actual and potential harm from gentrification, it is critical that policymakers consider how economic development policies impact and empower residents through a race equity lens. Only then will decision-makers understand how the legacy of racism has systematically deprived communities of color of resources, only to see new capital accompany wealthier and whiter residents as they move in and potentially price them out of the communities they built. Embracing a strong race equity focus will guide policymakers to establish stronger accountability measures and ensure collective community benefit from sustainable and equitable growth efforts.

[1] https://demography.cpc.unc.edu/2017/02/10/north-carolina-population-growth-at-highest-levels-since-2010/ and https://demography.cpc.unc.edu/2018/07/06/population-growth-may-be-more-concentrated-than-last-years-estimates-suggested/

[2] http://www.wakegov.com/planning/peopleandplaces/Pages/default.aspx

[3] https://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/Triangle_J_Profile_Final_31March2015.pdf

[4] https://www.ncjustice.org/publications/wage-growth-in-the-past-year-shows-slow-recovery/

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/27/upshot/diversity-housing-maps-raleigh-gentrification.html

[6] https://www.wunc.org/post/digging-gentrification-north-carolina

[7] https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/a_shared_future_can_gentrification_be_inclusive_0.pdf

[8] https://www.citylab.com/equity/2015/09/the-role-of-public-investment-in-gentrification/403324/

[9] http://www.coloroflawbook.com/

[10] https://dillonm.io/articles/Cortright_Mahmoudi_2014_Neighborhood-Change.pdf

[11] Ellen and O’Regan (2011); Freeman (2005); McKinnish, Walsh, and White (2010); Vigdor (2002)

[12] Ibid.

[13] https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/a_shared_future_can_gentrification_be_inclusive_0.pdf

[14] https://patch.com/north-carolina/charlotte/gentrification-charlotte-see-areas-most-affected and https://demography.cpc.unc.edu/2019/07/24/raleigh-and-charlotte-are-among-fastest-growing-large-metros-in-the-united-states/

[15] https://www.workers.org/2013/10/27/gentrification-rocks-north-carolina-working-class/

[16] https://www.wral.com/neighbors-fear-being-priced-out-of-historically-black-raleigh-neighborhood/16584624/

[17]https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/27/upshot/diversity-housing-maps-raleigh-gentrification.html

[18] Beale, C. L., & Fuguitt, G. V. (2011). Migration of Retirement‐Age Blacks to Nonmetropolitan Areas in the 1990s. Rural Sociology, 76(1), 31-43.

[19] Ibid.

[20] https://www.ncdemography.org/2018/03/22/are-nc-county-growth-patterns-shifting/

[21] https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/north-carolina/2019/measure/factors/141/description

[22] https://www.citylab.com/life/2013/05/why-segregation-bad-everyone/5476/

[23] https://source.wustl.edu/2013/11/effects-of-segregation-negatively-impact-health/

[24] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/27/upshot/diversity-housing-maps-raleigh-gentrification.html

[25] Chetty article: https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/newmto/

[26] https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/a_shared_future_what_more_do_we_need_to_know_0.pdf

[27] https://www.enterprisecommunity.org/policy-and-advocacy/policy-priorities/opportunity-zones-program

[28] Analysis from data shared from authors of Shifting Neighborhoods (2019), Richardson, Mitchell, Franco – https://ncrc.org/gentrification/

[29] Analysis from data shared from authors of Shifting Neighborhoods (2019), Richardson, Mitchell, Franco – https://ncrc.org/gentrification/

[30] Shifting Neighborhoods (2019) – https://ncrc.org/gentrification/

[31] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/business/opportunity-zones-congress-criticism.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

Justice Circle

Justice Circle